The conflict of the Basque people, or Euskaldunak, is a long-standing issue of autonomy that has spanned multiple centuries and transcends national borders. It has basis in the autonomy that the Basque people have held for much of their modern history, from the Kingdom of Navarre to the fueros system that guaranteed them rights above what many other Spanish citizens had. It also has basis in the preservation of Basque culture, for which many modern organizations exist.

As movements of national unity grew, the Basque people found themselves constrained by various attempts by the Spanish government to nationalize them. Even as Franco actively suppressed the population, the fervor for self-governance separate from the Spanish state, and even independence, has reigned in the Basque spirit and will continue to remain. The conflict has largely ended with the disarmament and disbanding of the ETA, a notable Basque terrorist organization, but cultural tensions and unforgotten hatred still remain.

Historical Background

The Basque culture is, perhaps, the oldest in Europe. It has been dated, conservatively, to around 5000 to 3000 BCE. This means this people have survived the Roman Empire; al-Andalusia, and various different potential threats to their culture relatively unscathed. Even Francoist Spain could not dislodge this ancient culture from its place in the Cantabrian Mountains. Many important figures such as St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, come from this heritage, and its people have played an important role in the Spanish culture in which they have participated for centuries.

The conflict as we know it extends to around the First Carlist War, although it could be traced as far back as the 1512 Invasion of Navarre or even further. The threat of the dissolution of the fuero system that protected much of the Basque autonomy became a rallying cry to the Carlist cause. As the 19th century moved into the early 20th century, further legislation and another war would see the powers of the Basque country quickly weaken in comparison to those of the Spanish state. The rise of Francoist Spain saw a significant uptick in the suppression of Basque culture, and the creation of the ETA became a reaction to the inactivity of the Basque government in exile to address this.

The end of the Francoist state saw an increase in the level of autonomy that the Basque Community had, with its official re-establishment within the confines of the Spanish state occurring in 1978. However, the ETA continued to exist for the next three decades as a terrorist organization, killing hundreds throughout Europe in its demands for Basque independence. By 2011, however, the organization had disarmed and, by 2018, it had disbanded. Even as the conflict’s combatants have been removed, the remnants of it still remain. Many still disregard the statutes of autonomy, and many still seek independence from Spain. The tension between those loyal to Madrid and those loyal to others still exist, and the remnants of the ETA continue to be prevalent in the Basque country.

Asier eta biok (Asier and I)

Many times, stories arise from two friends whose paths diverged. According to the Public Radio International, this was the case of Aitor Merino and Asier Aranguren. Raised as childhood friends in the Basque region, they both set off on their own ways at the age of 16: Aitor to become a successful TV actor in Madrid, Asier to become a Basque nationalist in their home country. They still kept in contact, but, in 2002, Aitor found out Asier was wanted for being a member of the ETA.

With his position in the public space, Aitor Merino released a documentary about the intricacies of his relationship with Asier and with his Basque identity titled “Asier Eta Biok” (Asier and I). Chronicling the intimacy of his intimate relationship with Asier as well as his personal connections with the region and the conflict, he creates a story that explores the complexity of these relationships and allows the platform to search for an understanding as to why his dear friend would join an organization such as the ETA. This expression of the searching that a Basque person may have to do to understand why someone near and dear allows an outsider to understand the complexities of the Basque conflict in a more intimate fashion.

This story shows a unique angle of the Basque conflict, one that is less about ethnic or linguistic tensions and more about ideological tension. Childhood friends and family members can end up on opposite sides of each other, as seen here. There’s an intimacy shared there that is relatively distinct from many other conflicts that are drawn between ethnic; religious; or linguistic conflict. The fighting that happens within the peoples themselves and the inner complexities that would drive one to join or brigade against the ETA. Even after the dissolution of the ETA, these sentiments remain. How should the Basque Country move forward when it is so fundamentally divided?

Brian Currin: Madrid didn’t want ETA to go away

In a conflict as politically and publicly discussed as the Basque one, especially with agents such as the ETA that troubled the process of peace in the region, there is going to be a significant international presence. Chronicled here is an interview from Brian Currin, a South African lawyer who has a history of human rights cases dating back to the Apartheid era, on his perspective of the negotiations of the Basque conflict. Although he has lived there for 15 years and says “the Basque Country has become like a second home nation for me”, he is not ethnically Basque. This gives a viewpoint from someone who is, at heart, removed from the conflict. While he might be intimately tied to the region, he is still an outsider.

As a result, he has a unique vantage point as someone with significant experience in the subject. From South African apartheid issues to Colombian cases, as a human rights lawyer, Currin has had to deal with various different viewpoints. However, he still calls the Basque issue an exemplary case. “Where in normal circumstances a government is a major stakeholder and, because of that, it must be and wants to be a participating party, here we got a situation where a government said “NO” and pushed us away.” Unlike other cases, where the government was willing to become a party in negotiations, the Spanish government has shied away from breaking the status quo. Currin attributes this coldness to a lack of compromise within Spanish culture, citing a lack of desire for them to achieve anything other than total victory.

What he does celebrate, and bring up, is the peace that has occurred at the grassroots level, which is unlike how it has been in many other places. He sees Basqueness as “an example of what nationalism can be” with its highly developed pluralism and its flourishing development in the face of a rise of a different sense of nationalism throughout Europe. As a result, Currin’s insight into the conflict showcases a further evolution into a region-wide discussion on how to move forward in the shadow of the ETA’s dismantlement. It expresses the freedom and the openness that the Basque people have now that not only is the ETA gone, but also the sort of oppression that had permeated the society for decades even after Franco had been relaxed.

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

The Basque language is unique to any other that exists on the European continent. It is neither Indo-European nor directly related to any other extant language. It is also considered one of the oldest languages in the world, with theories suggesting that it belonged to an ancient family of languages that had been otherwise wiped out by the encroachments of groups such as the Romans and Visigoths during the early centuries AD. Despite these encroachments and incursions into Basque lands, as well as the various periods where other kingdoms and countries held dominion over the Basque people, the language and culture endured to the modern day.

The Basque language is unique to any other that exists on the European continent. It is neither Indo-European nor directly related to any other extant language. It is also considered one of the oldest languages in the world, with theories suggesting that it belonged to an ancient family of languages that had been otherwise wiped out by the encroachments of groups such as the Romans and Visigoths during the early centuries AD. Despite these encroachments and incursions into Basque lands, as well as the various periods where other kingdoms and countries held dominion over the Basque people, the language and culture endured to the modern day.

Despite its linguistic isolation, it did not grow up alone on the Iberian Peninsula. For centuries, perhaps even millennia, Basque has intermixed, in varying degrees, with Spanish. Despite the logical separation due to separate language families, there is a lot of overlap between the two languages due to their geographic and historically cultural closeness. The languages share words for things such as boy and girl (‘niño/niña’ versus ‘nini’) as well as other words like ‘puppy’ (‘chachorro’ versus ‘txakur’), showcasing this sense of historical linguistic closeness despite their distance on the trees of language.

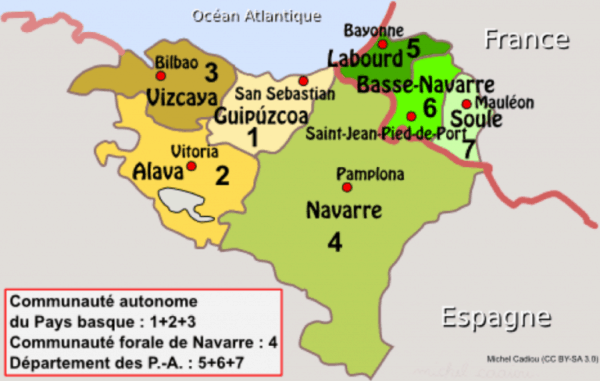

The Basque language itself encompasses seven regional dialects: Biscayan; Guipuzcoan; Upper Navarrese; Lower Navarrese; Souletin, and Labourdin, as well as the extinct Roncalese, spread around the border of France and Spain. Despite the cultural delineations that have been created by the separation of borders, the similarities of dialect across borders speak of a past that cared less about these lines and more about the people that communicated between them. In recent decades, however, significant efforts have been undertaken to ensure the continuation of the language’s prosperity. These include organizations such as the Euskaltzaindia, or the Royal Academy for the Basque language, which has existed for almost a century as an advocate for the structuring of Basque society around the language and culture. As a result, the language has been allowed to thrive post-Franco as an integral part of Spanish society in its region.

Resources

2018 World Press Freedom Index | Reporters Without Borders. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/ranking

500th Anniversary of the Conquest of Navarre. (2012). Retrieved December 15, 2018, from

http://nabasque.eus/old_nabo/Astero/Nafarroa_bizirik.htm

Bengtson, J. (2011). The Basque Language: History and Origin. International Journal of Modern Anthropology,1(4). doi:10.4314/ijma.v1i4.3

https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma/article/viewFile/66981/55097 ( The Basque Language: History and Origin by John Bengtson)

...Bombing of Guernica. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2018, from https://www.pbs.org/treasuresoftheworld/guernica/glevel_1/1_bombing.html

Basque Country. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Basque-Country-region-Spain

Collection of Laws. (2017, October 17). Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://www.wdl.org/en/item/17186/

ETA | Basque Separatism, Conflict, & Attacks. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/ETA

Jules Ferry | French statesman. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jules-Francois-Camille-Ferry

Kingdom of Navarre. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Kingdom-of-Navarre

Spain - Franco’s Spain, 1939–75. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain/Francos-Spain-1939-75

Tomás de Zumalacárregui y de Imaz. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tomas-de-Zumalacarregui-y-de-Imaz

Coates, E. M. (2004). The Birth of Basque Nationalism. Retrieved November 27, 2018, from

https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~emcoates/eta/birthofnationalism.html

Colocan en Berango una pancarta en la que se ensalza a los militantes de ETA "de hoy, ayer y maana". (2011, September 27). Retrieved from

https://www.elcorreo.com/alava/20110927/mas-actualidad/politica/pancarta-berango-201109271439.html

COUNTRY COMPARISON :: DISTRIBUTION OF FAMILY INCOME - GINI INDEX. (n.d.). Retrieved October 21, 2018, from

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html

Douglass, W., & Zulaika, J. (1990). On the Interpretation of Terrorist Violence: ETA and the Basque Political Process. Comparative Studies in

Society and History, 32(2), 238-257. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/178914

Elkarmedia. (n.d.). Presentation. Retrieved November 16, 2018, from https://www.euskaltzaindia.eus/en/centenary

Elsner, E. (1928). The romance of the Basque Country and the Pyrenees. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from http://navarra.es

Euromosaic - Basque in Navarre. (n.d.). Retrieved October 21, 2018, from https://www.uoc.edu/euromosaic/web/document/basc/an/i2/i2.html

ETA: Basque separatists plan to unilaterally disarm on Saturday. (2017, April 07). Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-

39512637

First Carlist War. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.spanishwars.net/19th-century-first-carlist-war.html

Harrison, J. A. (1903). Spain. Akron, OH: Saalfield Pub.

Idoiaga, G. E. (n.d.). The Basque Conflict: New Ideas and Prospects for Peace (Rep.). Retrieved October 21, 2018, from U.S. Insitute of Peace

website: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/sr161.pdf

LeClerc, J. (n.d.). L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde: Page d'accueil. Retrieved November 19, 2018, from http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/

Fernando Molina. (2014). Lies of Our Fathers: Memory and Politics in the Basque Country Under the Franco Dictatorship, 1936-68. Journal of

Contemporary History, (2), 296. Retrieved from https://login.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.43697301&site=eds-live

OECD Regional Outlook 2016. (n.d.). Retrieved October 21, 2018, from https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/regional-outlook-2016-

Ormazabal, M., Aizpeolea, L. R., País, E., Vera, S., & Keaten, J. (2018, May 03). ETA releases statement announcing its complete dissolution.

Retrieved from https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/05/03/inenglish/1525349131_830131.html

Payne, S. (1971). Catalan and Basque Nationalism. Journal of Contemporary History, 6(1), 15-51. doi:10.1177/002200947100600102

Ray, N. M., & Bieter, J. P. (2015). ‘It broadens your view of being Basque’: identity through history, branding, and cultural policy. International

Journal of Cultural Policy, 21(3), 241–257. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1080/10286632.2014.923416

Sabino Arana. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2018, from http://www.bilbaoturismo.net/BilbaoTurismo/en/outdoor-art/sabino-arana

Share, D. (1986). The Franquist Regime and the Dilemma of Succession. The Review of Politics, 48(4), 549-575. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1407383

Spain. (1979). Spanish constitution, 1978. Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Oficina de Información Diplomática. Retrieved October 29,

Spain autonomous communities comparison: Basque Country vs Navarre Population 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved from

Spain - Basques. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2018, from https://minorityrights.org/minorities/basques/

Spain OECD. (2016, October). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy/profile-Spain.pdf

Strong, W. T. (1893). The Fueros of Northern Spain. Political Science Quarterly, 8(2), 317-334. doi:10.2307/2139647

The Fueros: Origin of the Basques' special status. (2009, June 30). Retrieved December 12, 2018, from http://www.basquecountry.eus/t32-

448/en/contenidos/informacion/historia/en_429/historia_i.html

The World Factbook: SPAIN. (2018, October 17). Retrieved October 21, 2018, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-

Velde, F. (2005, January 13). The Salic Law. Retrieved from https://www.heraldica.org/topics/france/salic.ht

Whitfield, T. (2015). The Basque conflict and ETA: The difficulties of an ending (pp. 1-16) (United States, United States Institute of Peace).

Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR384-The-Basque-Conflict-and-ETA-The-Difficulties-of-An-

Ending.pdf.

Woodworth, P. (2007). Basque country : a cultural history. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Zirakzadeh, C. E. (1991). A Rebellious People : Basques, Protests, And Politics. Reno, Nev: University of Nevada Press.

Credits

Asier ETA biok. (2015, December 15). Retrieved January 18, 2019, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3183716/

Copyrighted by User:Error, 2004 - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by IngerAlHaosului using CommonsHelper., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9726619, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/38/GuernicaGernikara.jpg

Dani Blanco [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5d/Kofi_Annan_at_the_International_Conference_to_Promote_the_resolution_of_the_conflict_in_the_Basque_Country.jpg

Daniele Schirmo aka Frankie688 [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Basque_Country.svg

ETA (Document by ETA sent to media) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Armategia_gizarte_zibilaren_esku_utzi_duela_iragartzen_duen_adierazpena.pdf

Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla from Sevilla, España - "Don Tomás Zumalacárregui"., CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51650667

Leclerc, J. (n.d.). Le Pays basque. Retrieved January 18, 2019, from http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/europe/espagnebasque.htm

Ottaviani [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sabino_arana_goiri_1865-1903.JPG

Paco Marí [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Luis_Carrero_Blanco,_1963_(cropped).jpg

Unknown - Unknown, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30076488, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Logos_of_ETA#/media/File:Logo_of_Euskadi_Ta_Askatasuna.png

www_ukberri_net [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Agur_eta_ohore_gudari_eguna_2011.jpg