Catalan is historically spoken in several Western European countries and regions, including Catalonia, the French Department of Western Pyrenees, Andorra, Eastern Aragon, Valencian Community, the Balearic Islands, and Alghero (Sardinia). The conflict between Castilian Spain and Catalonia can be dated to the first Catalonian rebellion against Spanish rule in the mid-17th century and then traced through the rise of Catalonian nationalism in the 19th and 20th centuries. The conflict between their languages, Castilian Spanish and Catalan, can be classified contemporarily as a competition between dominant and non-dominant languages, but historically the conflict was geopolitical. The geopolitical conflict can be summarized as two nation building projects that have clashed for centuries: that of a Catalonia with aspirations of independence and that of a Spain with an agenda for unity.

Catalonia has historically been at odds with the Castilian state, whose efforts to unify Spain and instill nationalism through the vehicle of Castilian (i.e. “standard”) Spanish threaten Catalonia’s identity. Catalan was first infringed upon following the War of Spanish Succession, when the Bourbon monarchy signed the Nueva Planta decrees (1707-1716), enforcing Castilian as the sole official language of Spain and reducing the cultural and linguistic footprint of Catalan [Guibernau, 2000; Narotzky, 2019]. Throughout the following centuries Catalan repression continued, and by the 20th century the use of Catalan was strongly regulated by the Bourbons who required the use of Castilian in all public accomodations and in education. This repression grew first under Miguel Primo de Rivera and then by the Falangist regime that ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War (1936- 1939), leading to a system where Catalan was fully banned from public use. The post-Franco Spanish constitution of 1978 recognized the right of self-government for all nationalities and regions [Constitute, n.d.], resulting in a renewed Catalonian push for independence centered around their language and culture [Guibernau, 2000; Narotzky, 2019].

Modern expressions of this linguistic tension are reflected in a heightened attention to elements of Catalan history and culture that highlights the Renaixença (Catalan Renaissance) of the1830s-80s, popular music, and sports rivalries such as Futbol Club Barcelona vs. Real Madrid Club de Fútbol [Bisht, 2018; Eaude, 2011]. Above all else, however, Catalonian separatists have consistently relied upon their language, Catalan, to frame their expression of political and cultural independence.

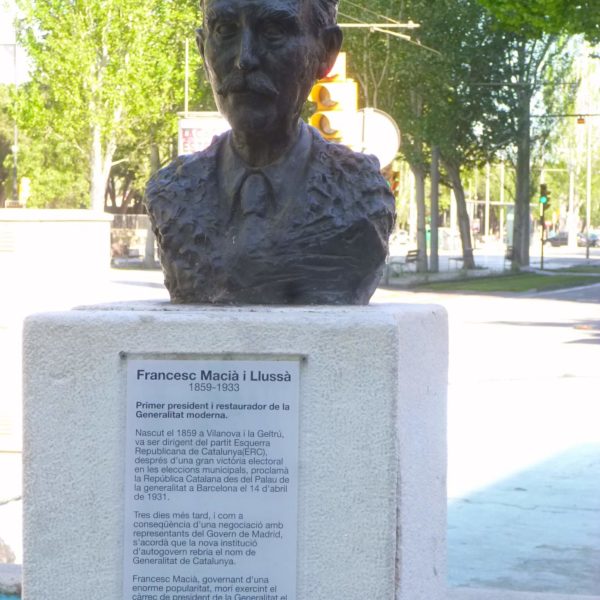

Historical Background

For centuries, the history of Catalonia has been intertwined with that of Spain and the various other kingdoms and states of the Iberian Peninsula. The historical origins of the Moorish invasion of Spain are disputed, but between 711 and 720 CE the forces of Jabal At-Tariq conquered most of modern-day Spain and Portugal, creating Al-Andalus, the Muslim Kingdom of Spain [BBC, 2009]. Parts of Spain would remain under the influence of Al-Andalus until 1482; Northern Catalonia, however, remained under Muslim control for less than a century, from about 720 until 801 CE [“Al-Andalus,” 2019]. Beginning with the conquest of Girona in 785, the area was then dominated by the Kingdom of the Franks, and after the invasion of Louis the Pious in 801, the County of Barcelona became part of “Marca Hispanica” (Spanish March) [Chandler, 2017]. This region was led by counts who recognized the sovereignty of the Carolingians and was established as a buffer region against military incursions by Al-Andalus to the south [Chandler, 2017; Phillips, W.D. & Phillips C.R., 2010: 60-61]. However, by the end of the 10th century, North Catalonia operated as an independent state with little interference from the fragmented Frankish empire under which it was created [Sobrer, 2013]. Southern Catalonia would leave Al-Andalus control during the mid-12th century. Due to the varied influences, Catalonia has long been set apart from the rest of Spain.

![This is a map of what is now the border region between modern France and Spain circa 806 CE. The Spanish March, or “Marca Hispanica”, lay in what is now northern Catalonia and constituted some of the southern-most reaches of the Carolingian Empire. While it remained as a part for a few centuries, its remote distance from the capital in Aachen meant that it could quickly become self-governing and, within a couple of centuries, it was able to operate relatively independently [“Carolingian Dynasty,” 2019].](https://www.languageconflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Marca_Hispanica_Longnon_806-600x582.png)

Spain circa 806 CE. The Spanish March, or “Marca Hispanica”, lay in what is now northern

Catalonia and constituted some of the southern-most reaches of the Carolingian Empire. While it

remained as a part for a few centuries, its remote distance from the capital in Aachen meant that

it could quickly become self-governing and, within a couple of centuries, it was able to operate

relatively independently [“Carolingian Dynasty,” 2019].

The colonial ventures of the Spanish Crown saw the increasing power and influence of Castile and, with it, the Castilian Spanish language. This decline in relative influence on the part of Catalonia culminated in restrictions on Catalan institutions and the destruction of the medieval liberties set in place previously, after the territories of the Crown of Aragon had the misfortune to support the losing side (that of Archduke Charles of Habsburg) in the 1710-1714 War of Spanish Succession [“Catalonia Profile,” 2018; Guibernau, 2013: 2; Narotzky, 2019: 34-35; Rodriguez, 2019]. Following the War, the Catalan state was dissolved, and the Bourbons became absolute monarchs of the newly founded Kingdom of Spain. This, in turn, led to all Catalan institutions – the courts, city councils, universities, etc. - also being dissolved, and Castilian being officially imposed throughout Catalonia. The enforcement of Castilian as an official language began at the highest level – in the Royal court – and gradually pervaded other social institutions. By 1768, schools were required to teach in Castilian [Siguán, 1993], an act that was enshrined in the 1857 Moyano Law [Iglésias, 2019].

In response to the imposition of Castilian on a society whose native language was Catalan, where it was still the language spoken in private contexts, Catalonian intellectuals began a literary renaissance, the Renaixença, in the mid-1800s [Guibernau, 2013: 2]. This renaissance reinvigorated the Catalan language, traditions, and culture, and facilitated the rebirth of Catalan nationalist movements that had been sidelined since their defeats in the previous century [Narotzky, 2019: 36]. These 19th century nationalistic movements in Catalonia were once again defeated in the early 20th century, first by Primo de Rivera in the 1920s and then by Francisco Franco in the 1930s. Then, at the end of 40 years of Francoist rule in 1975 and the restoration of democracy to Spain, the pressure of newly permissible protest movements led to the 1979 Statute of Catalan Autonomy, and Catalan became the joint official language of Catalonia, alongside Castilian Spanish.

In 2006, the 1979 Statute was revised to offer Catalan’s government greater power and financial autonomy, and the term “nation” was used to describe Catalonia [BBC, 2018]. This revision was, itself, partially struck down by the Constitutional Court of Madrid, as it was ruled that Catalonia had no legal right to be recognized as a nation. This reignited tensions, paving the way for a successful 2017 referendum to fully separate Catalonia from Spain; however, the referendum’s results were declared illegal by the Constitutional Court of Madrid, sparking protests across Catalonia, as the conflict over Catalonia’s independence continues [BBC, 2018].

Real Madrid 11- 1 FC Barcelona: The Story of El Clásico

Many football fans hesitate to mix their political affiliations with their love of the sport. Those who do combine their politics with their fandom are called ultras, fans who are dedicated to their clubs to the point of hooliganism or violence against rival clubs. However, some clubs are so deeply steeped in the politics of their region that it becomes impossible to separate the two, as in the case of Real Madrid CF and FC Barcelona. These two clubs, amongst the most dominant in Spain’s storied football history, are world famous for their rivalry. Fans all over the world know of the two most popular Spanish clubs: El club blaugrana (The Blues and Reds, i.e. Barcelona, where in Catalan, blau means ‘blue’ and grana means ‘deep red’) and El club merengue (The Whites, i.e. Real Madrid).

During the time of Francisco Franco, football fans perceived Real Madrid as the government's team [Bisht, 2018]. In the eyes of opponents of the regime, the club received preferential treatment from Franco, particularly against Atletico Bilbao and FC Barcelona, teams that were, respectively, cultural rallying points for the Basques and Catalans [Eaude, 2011: 294- 295; Child, 2018; Kelly, 2019]. While Atletico Bilbao strictly upheld, and still upholds, a policy of recruitment from only Basque sources, FC Barcelona (known as Futbol Club Barcelona at the time due to Castilian policy) recruited widely. “Més que un club” (‘More than a club’) is the motto of FC Barcelona, and the team is seen as a cultural touchstone for many Catalans. Martí Dalmases, a long-time fan of Barcelona, in an article for Boston’s NPR station WBUR, wrote “There are lots of people who sign up their child as a Barça member before they go to the registry to get the birth certificate” [Mount, 2015]. FC Barcelona’s political roots run deep. According to historian Josep Solé i Sabaté, “FC Barcelona was the refuge and the cradle, diluted and vague, of the essence of Catalonia - this feature maintained it and made it grow right down to today” [Sabaté, 2005]. Support of the team became the safest legal way for Catalonians to express national pride during the Francoist regime. Today, FC Barcelona is still viewed as a proxy of the national team Catalonia is prevented from having.

Despite measures to keep football neutral, political tensions between football teams sometimes came to a head during the Francoist period. One of the more egregious examples of this occurred in 1943, during the Copa del Generalísimo semi-final between Barcelona and Madrid. Barcelona had comfortably won the first leg 3-0 [Bisht, 2018]. Then, however, the team was allegedly visited before the second leg by the Director of State Security, who reminded the team of the state’s generosity in allowing them to play the match. The team would then go on to lose the match 11-1, leaving the combined score to be 11-4, which resulted in their elimination. Controversy arose over the result, and many questioned the sudden change, increasing tensions. Although Real Madrid, both historically and today, is known as one of the most dominant teams in Spanish football, and the rivalry between Catalonia and Madrid is one of the most storied in the history of the sport, the undertones of societal division that the rivalry has taken on extend far past the end of Franco.

Even today, there is a feeling in Catalonia that Real Madrid is still the team of the government and the political establishment [Bisht, 2018; Child, 2018; Kelly, 2019]. Conversely, Luis Camps claims in “More than a Game: How politics and football interplay in Spain” that “Real Madrid fans don't want the club to be involved in politics” [Child, 2018]. The history of the two clubs, however, creates a conflicting narrative, and Real Madrid’s current association with Spanish royalty makes it difficult to detangle politics from sport in this instance. Juan Carlos I, former King of Spain, is a vocal supporter of el club merengue, while the current king, Felipe VI, has been spotted at many matches, continuing a line of Spanish leadership associating with the team [Kelly, 2019]. Even the title of “Real” Madrid (meaning ‘royal’) reflects association with Spanish royalty and, by extension, loyalty to the Spanish government [“Spain’s Constitution,” n.d]. Furthermore, Real Madrid president, Florentino Pérez, owns multiple businesses that are deeply intermingled with the Spanish state administration. His box at the Real Madrid stadium – known colloquially as "palco del Bernabéu" – is said to be more important to political decision making than the Spanish parliament, further increasing the Catalonian sense that the team is a political establishment [Alameda, 2016].

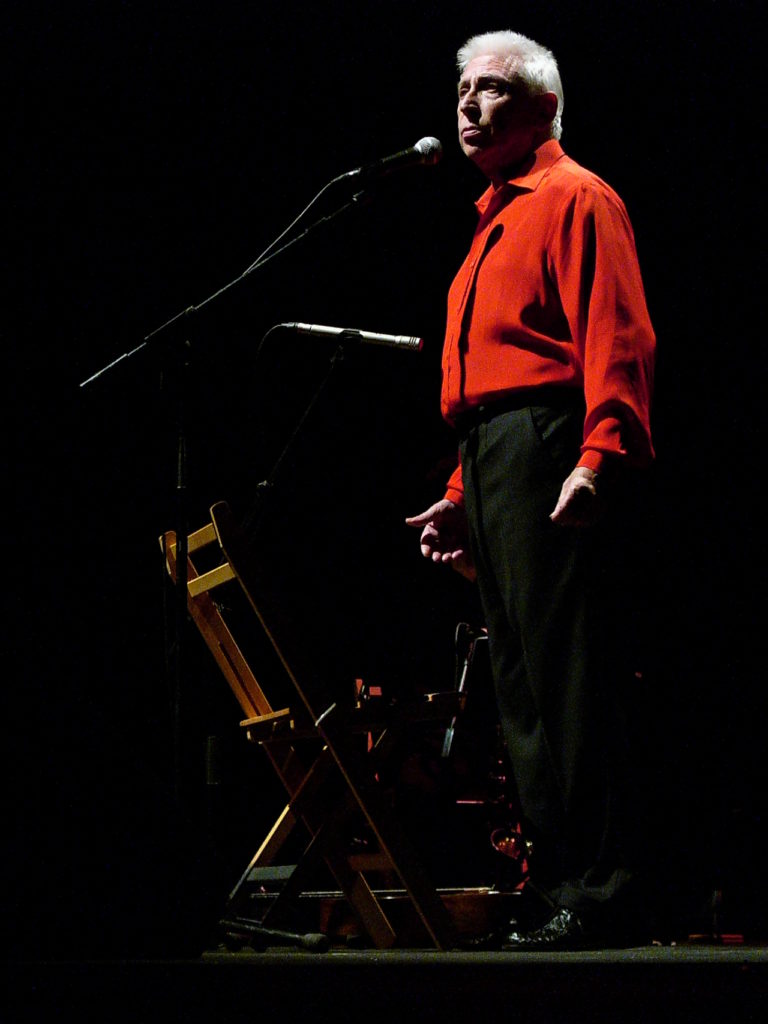

La Nova Cançó

The Nova Cançó, or “New Song”, was a Catalan cultural movement that arose during the Francoist regime and challenged the censorship of Catalan culture and language [“Raimon,” n.d.]. Its influences, locally, were as significant as the French chanson and African American spirituals of the 20th century, according to the Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media [Downing, 2011: 293]. Nova Cançó also embodied elements of anti-fascist and pacifist movements and a spirit of revitalization for expression of the Catalan language. The movement originated in the late 1950s, when a group that called themselves the ‘Setze Jutges’, or sixteen judges, began to sing in Catalan at song festivals [Downing, 2011: 293; Eaude, 2011: 177-78]. Many of their songs, like Raimon’s “Al vent” (In the Wind), were not explicitly political, but used language that evoked images of freedom and used literary devices in order to imply increasingly political messages. These Catalan songs, while officially prohibited, did not attract the attention of the censors at first [Downing, 2011: 294; Eaude, 2011]. While these musical messages were non-controversial in the beginning, they became far more provocative (though seldom directly confrontational) as the protest movement grew and the position of the regime became more precarious on the world stage.

Many of these Nova Cançó singers were extremely popular despite the obstacles of censorship. While their song lyrics would sometimes be arbitrarily censored before concerts, their audiences, knowing the songs beforehand, would sing the original (and now censored) lyrics in the performer’s stead [Downing, 2011: 294]. The Nova Cançó group and other similar movements that emerged at this time roughly paralleled contemporaneous counterculture movements in other places, like the United States, seeking to combat oppression through popular and nonviolent methods. For the Nova Cançó movement, the importance of singing in Catalan was twofold. First, the language’s status as an oppressed medium of expression gave meaning to their songs beyond their lyrics. Second, the efforts of songwriters like Raimon allowed for both poets and ordinary people alike to have their voices heard. When their lyrics or their titles were banned, these artists would seek and find ways to convey the same message in ways that were more difficult for the censors to detect. The songs became more poetic, using linguistically crafted metaphors to set out and highlight the differences between Franco and Catalonia as well as between oppression and freedom. Nova cançó also helped to demonstrate that Catalan was not a folkloric, old-fashioned language, but instead capable of expressing modernity like any other national language.

In this vein, many of the singers became like Verdaguer, both chroniclers of the past and heralds of a new tradition. Their songs, simple as they were, reflected yearning for freedom in both the youth and the older generation. Franco’s regime was slow to discern the political element in these creations, as many of these songs were ostensibly about innocuous topics like motorbikes. While some songs like Raimon’s “Diguem No” (Let’s Say No) were censored by the regime, others, such as Joan Manuel Serrat’s “Cançó de matinada” (Early Morning Song) were not and managed to climb to the number one spot on the Spanish pop charts. The occasional eruption of overtly subversive content in these songs led to a significant strengthening of censorship in the country. Although their movement would fade away not long after the fall of the Francoist regime, the movement’s principles and spirit would be revived through Rock Català and other protest movements of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

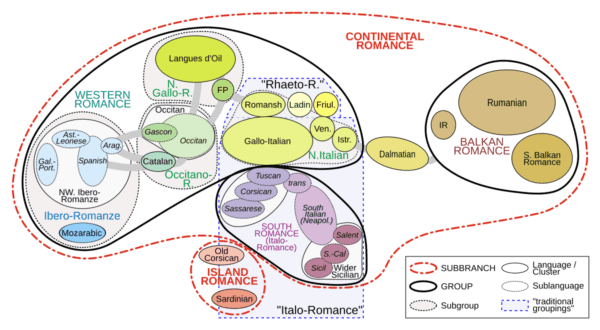

1. Genealogy/Relatedness

Catalan (Valencian) is usually placed within the Occitano-Romance branch of Gallo-Romance languages. It shares many traits with the other neighboring Romance languages (Occitan, French, Italian, Sardinian as well as Spanish and Portuguese). However, despite being geographical neighbors with Spanish and Portuguese, Catalan has significant differences with these two languages in terms of pronunciation, grammar, and especially vocabulary. Catalan is closest to Occitan (a dialect of Southern France) and to a lesser extent to other Gallo-Romance languages (Franco-Provençal, French, Gallo-Italian) [Wheeler, 2005; Koryakov, 2001]. Catalan is also a part of the Ibero-Romance subfamily, which also includes Portuguese, Aragonese, and Asturian-Leonese. Note that while both Catalonia and Aragon were once united under the Crown of Aragon from 1162 until 1712 (and remain under one leadership through the Crown of Spain despite fracturing into what became much of the eastern coast of modern Spain), the two regions are quite distinct linguistically. Aragon (centered on Zaragoza with 1/5 the population of Catalonia) has a language more closely related to Castilian Spanish, while the Catalan language of Barcelona and the rest of that province is most closely related to Occitan (or Langue d’oc) [Koryakov, 2001].

2. Phonetics/Phonology

Catalan has a greater number of vowels and consonants than Spanish. It includes seven stressed vowels: /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/ (plus one unstressed /ə/), a common feature in Western Romance, with the exception of Spanish, which includes only five vowels /i, u, e, o, a/ [Carbonell & Llisterri, 1999]. Catalan includes 23 consonants [Carbonell & Llisterri, 1992], while Castilian Spanish includes 20 consonants [Martínez Celdrán et al., 2003].

3. Morphology and Grammar

Catalan and Spanish both have morphological and grammatical properties commonly found in other Western Romance languages. For example, both languages use definite and indefinite articles, and their nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and articles are inflected for gender (masculine and feminine), and number (singular and plural). There is no case inflection, except in pronouns. Verbs, on the other hand, are highly inflected for person, number, tense, aspect, and mood. There are no modal auxiliaries [Swan, 2001].

A feature of Catalan that is distinctive and contrasts with other Iberian Romance languages is the general lack of masculine markers (like Italian -o), a trait shared with French and Occitan.

The primary word order is subject-verb-object (SVO), however it is very flexible. [“Catalan,” n.d.].

4. Lexicon and Vocabulary

Catalan has borrowed extensively from Greek and Latin. In the 14th and 15th centuries Catalan had a far greater number of Greco-Latin loanwords than other Romance languages. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, most literate Catalan speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words both into their Catalan writing and speech. The vocabulary of Catalan most closely aligns with other members of the Gallo-Romance family (e.g., Occitan), rather than with languages of the Ibero-Romance family. For Catalan, early differentiation from other Iberian Peninsula dialects of Latin, the influence of Gothic (a Germanic language), mutual influence between Catalonia and Southern France, and less borrowing from Arabic than other Iberian languages all combine to make the lexical distinctions between Catalan and Spanish more robust than they might otherwise be [Ferrater, et al., 1973].

As for Castilian Spanish, some authors estimate that seventy-five percent of Spanish words have come from Latin and were in use in Spain before the time of Christ. The remaining 25 percent come from other languages, like Arabic, Germanic, and Celtic [Chandler & Schwartz, 1991; Dworkin, 2012].

5. Orthography / Writing System

Like many other Romance languages, the Catalan alphabet derives from the Latin and consists of the 26 letters. Additionally, a number of letter-diacritic combinations are used, but they do not constitute distinct letters in the alphabet: à, é, è, í, ï, ó, ò, ú, ü and ç1 [Wheeler, 2005].

The Spanish language is written using the Latin script with one additional letter: eñe ⟨ñ⟩, for a total of 27 letters. Similar to Catalan, Spanish uses diacritics to mark the stress over any vowel: ⟨á é í ó ú⟩ [Butt & Benjamin, 2011].

6. Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

Catalan originally developed in and around the area that would become the County of Barcelona, which was formed around the turn of the 9th century AD after the region’s conquest by the Franks [Chandler, 2017; “Catalonia Profile,” 2018]. Catalan does not have the same level of Moorish influence as Spanish does because of the comparatively short amount of time that the region encompassing modern Catalonia spent under Al-Andalus (from 720 until 801). Their lack of influence is likely due to structural factors that allowed the Franks to coalesce and push the Muslim forces out of the areas that would later become Catalonia [Phillips & Phillips, 2010: 49, 59-61; Chandler, 2017]. Instead, the influence of the Franks, and later Aragon, permitted the region’s culture and language to develop and flourish. Due to the extended influence of the Crown of Aragon in Iberia (Valencia), adjacent regions of southern France, and the Western Mediterranean (Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands), the language spread into nearby regions and is still in use today to varying degrees in French Catalonia, Andorra, Valencia, Alicante, and the Balearic Islands [Burgen, 2012; Plataforma per la Llengua, n.d.].

In the 15th century, the Catalan language waned in importance after the decline of the House of Barcelona and the rise of the interests of Aragon. The installation of Ferdinand as king of Aragon and his marriage to Isabella of Castile effectively united Spain under Castilian interests, creating tension between the Catalan and Spanish speakers that boiled over in the 17th and early 18th centuries [Narotzky, 2019: 34; Rodriguez, 2019]. For over 250 years, from the subjugation of Catalan institutions following the victory of King Philip V (who Catalonia opposed) in the 1714 War of the Spanish Succession until the 1976 dissolution of the Falangist (Francoist) State and restoration of democracy, Catalan language speakers experienced varying levels of linguistic and cultural oppression in Spain with only intermittent periods of relief [Guibernau, 2013; Narotzky, 2019: 37-38; Plataforma per la Llengua, n.d.]. However, throughout this period, Catalan nationalist spirit continued to grow. Through endeavors such as La Nova Cançó and the environment fostered by FC Barcelona, the spirit of Catalan culture continued to thrive wherever it could and however it could [Sabaté, 2005; Eaude, 2011; Child, 2018].

Today, through the cultivation of freedoms in post-Francoist Spain and the accommodation afforded to minority languages through the 1978 Constitution and the 1979 Statute of Autonomy, Catalonia is a region with a vibrant cultural and linguistic community. The language is in no danger of extinction; it is a well-respected language in Europe, and policies within Spain encourage its use alongside Spanish [Plataforma per la Llengua, n.d.]. In Valencia, where it is called Valencian but considered the same language as Catalan, it continues to flourish. Catalonia’s future as a part of Spain is today in a somewhat precarious position due to the recent pro-independence referendums and mass protests of central government repression of declarations of independence. It would not be far-fetched to imagine that Catalan might one day be the official language of an independent Catalonia.

Resources

Alameda, F. (2016, May 27). Florentino Perez: The Failed Politician Who Became Real Madrid's Powerful President. Vice. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/4xzw7g/florentino-perez-the-failed-politician-who-became-real-madrids-powerful-president.

Alarcón, A., & Garzón, L., eds. (2011). Language, Migration and Social Mobility in Catalonia.

Al Jazeera. (2019, October 18). Timeline of Catalan separatism that has rocked Spain. Retrieved June 20, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/timeline-catalan- separatism-rocked-spain-191018203010894.html.

Agència Catalana de Notícies (ACN). (2014, September 11). 1.8 million Catalans form an 11km- long flag mosaic supporting November's independence vote. Retrieved from https://www.catalannews.com/politics/item/1-8-million-catalans-form-an-11km-

long-flag-mosaic-supporting-november-s-independence-vote.

Barros, L. (2019, January 7). La matanza de católicos en la Segunda República: un genocidio no reconocido. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.elespañoldigital.com/matanza-

catolicos-segunda-republica-genocidio-no-reconocido/.

Balcells, A, Walker, G. (1996). Catalan nationalism: past and present. St. Martin’s Press : Macmillan Press.

BBC. (2009, September 4). Muslim Spain (711-1492). Retrieved June 25, 2021, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/history/spain_1.shtml.

BBC. (2014, November 10). Catalonia vote: 80% back independence - officials. Retrieved January 5, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29982960.

BBC. (2017, October 1). Catalan Referendum: Clashes as Voters Defy Madrid. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-41457238.

BBC. (2018, May 14). Catalonia profile - Timeline. Retrieved June 20, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-20345073.

BBC. (2018, August 19). The French connection: How Catalonia got its ballot papers. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-45226484.

BBC. (2019, October 14a). Violent clashes erupt as Spanish court jails Catalonia leaders. Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-49974289.

BBC. (2019, October 18b). Catalonia's bid for independence from Spain explained. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29478415.

BBC. (2019, October 18c). Catalonia protests: Marches and general strike paralyse Barcelona. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50098268.

BBC. (2019, December 18d). El Clásico: Catalan protests at football match in Spain. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50845732.

BBC. (2021, June 22). Spain Pardons Catalan Leaders Over Independence Bid. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57565764.

Bisht, P. (2018, May 8). A Barcelona Fan's Exploration of Francisco Franco's Fascist Real Madrid. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from https://www.footballparadise.com/francisco- franco-madrid/.

Burgen, S. (2012, November 22). Catalan: a language that has survived against the odds.

Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/nov/22/catalan-language-survived.

Butt, J., & Benjamin, C. (2011). A New Reference Grammar of Modern Spanish (5th ed.). Oxford: Routledge.

Calamur, K. (2017, October 4). The Spanish Court Decision That Sparked the Catalan Independence Movement. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/10/catalonia-referendum/541611/.

Carbonell, J. F., & Llisterri, J. (1992). Catalan. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 22(1-2), 53–56.

Carbonell, J. F., & Llisterri, J. (1999). “Catalan.” Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the usage of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61-65.

Castro, L. (2013). What’s Up with Catalonia?: The Causes Which Impel Them to the Separation. Catalonia Press. Retrieved from http://files.cataloniapress.com/files/WhatsupCATcc.pdf.

“Catalan.” World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) Online. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

Catalan language. (2020, June 29). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catalan_language

Chandler, R. E., & Schwartz, K. (1991) [1961]. A New History of Spanish Literature. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Chandler, C. J. (2017). Carolingian Catalonia: The Spanish March, 778–988. The Heroic Age, (17). Retrieved from https://www.heroicage.org/issues/17/chandler.php.

Child, D. (2018, April 17). More than a game: How politics and football interplay in Spain. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/4/17/more-than-a-game-how-politics-and-football-interplay-in-spain.

CIA. (n.d.).The World Factbook: Spain. (2021, June 15). Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/spain/.

Coll, G. P., & Agència Catalana de Notícies (ACN). (2010, July 10). Catalonia answers back through a colossal demonstration: 'We are a nation'. Retrieved January 2, 2020, from https://www.catalannews.com/politics/item/catalonia-answers-back-through-a-colossal-demonstration-we-are-a-nation.

Constitute. (n.d.). Spain's Constitution of 1978 with Amendments through 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2019, from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Spain_2011.pdf?lang=e.

Constitution of Spain. (2020, June 26). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 27, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Spain.

Conversi, D. (2000). The Basques, the Catalans and Spain: alternative routes to nationalist mobilisation. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Cook, L. (2019, December 19). Spain rocked by rulings that renew questions over Catalonia.

Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://apnews.com/b3bdd59b404384b58f663c2b679638f0.

Dowling, A. (2013). Catalonia Since the Spanish Civil War. Reconstructing the Nation. Sussex Academic Press.

Dowling, A. (2019). When national symbols divide: the case of pan-Catalanism and the Països Catalans. Journal of Iberian & Latin American Studies, 25(1), 143–157. https://doi- org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1080/14701847.2019.1579494.

Downing, J. (2011). Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=474298&site=ehost-live.

Dworkin, S. N. (2012). A History of the Spanish Lexicon: A Linguistic Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eaude, M. (2011). Catalonia: A Cultural History. Luton: Andrews UK. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=409788&site=eds-live.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, July 09). Al-Andalus. Retrieved June 25, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Al-Andalus.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, August 20). Carolingian dynasty. Retrieved June 25, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Carolingian-dynasty.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, December 21). Francesc Macià. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francesc-Macia.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019, December 29). Spain. Retrieved January 2, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain.

Edwards, S. (1999). `Reconstructing the nation’: The process of establishing Catalan autonomy. Parliamentary Affairs, 52(4), 666.

Faus, J. (2019, December 19). 'El Clasico' sparks pro-independence protests near Barcelona stadium. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-soccer-spain-fcb-mad-protest/el-clasico-sparks-pro-independence-protests-near-barcelona-stadium-%20idUSKBN1YM21Y.

Ferrater et al. (1973). “Català.” Enciclopèdia Catalana. Vol. 4 (in Catalan) (1977, corrected ed.). Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana. pp. 628–639.

Frayer, L. (2014, November 10). Catalonia Votes For Independence; Spain Says It Won't Happen. Retrieved January 5, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2014/11/10/362952892/referendums-outcome-indicates-catalonias-desire-for-independence.

Generalitat de Catalunya [Gencat]. (2018, November 19). The contemporary Government of Catalonia (20th and 21st centuries). Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://web.gencat.cat/en/generalitat/historia/generalitat-contemporania/.

Generalitat de Catalunya [Gencat]. Autonomy Statute for Catalonia, Autonomy Statute for Catalonia (1982). Barcelona. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://web.gencat.cat/en/generalitat/estatut/.

Guibernau, M. (2004). Catalan Nationalism : Francoism, Transition and Democracy. London: Routledge. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna

Guibernau, M. (2000). Spain: Catalonia and the Basque country. Parliamentary Affairs, (1), 55. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao& AN=edsgcl.62547358&site=eds-live.

Guibernau, M. (2013). Secessionism in Catalonia: After Democracy. Ethnopolitics, 12(4), 368– 393. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1080/17449057.2013.843245.

Hayward, B. (2017, October 2). Behind the Barcelona chaos: Why the Catalan club matters beyond just football. Retrieved July 11, 2020, from https://www.sportingnews.com/ca/soccer/news/behind-the-barcelona-chaos-why-the-catalan-club-matters-beyond-just-football/1f1r6chls307b1afgjnponv7rm.

Iglésias N. (2019) Language Policies in Contemporary Catalonia: A History of Linguistic and Political Ideas. In: Casanovas P., Corretger M., Salvador V. (eds), The Rise of Catalan Identity. Springer, Cham.

Jones, S. (2017, March 13). Catalan ex-president Artur Mas barred from holding public office.

Retrieved January 5, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/13/catalan-ex-president-artur-mas-

barred-from-holding-public-office.

Jones, S. (2019, October 14). What is the story of Catalan independence – and what happens next? Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/14/catalan-independence-what-is-the-

Kassam, A. (2014, September 29). Catalonia independence referendum halted by Spain's constitutional court. Retrieved January 5, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/29/catalonia-independence-

Kelly, R. (2019, March 1). General Franco, Real Madrid & the king: The history behind club's link to Spain's establishment. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from https://www.goal.com/en-us/news/general-franco-real-madrid-king-history-behind-

clubs-link/fcoqldp8h2bb1841o2rspmuhe.

Keating, M. (1996). Nations against the state: the new politics of nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia and Scotland. Palgrave.

Koryakov, Y. (2001). Atlas of Romance languages. Moscow.

La Vanguardia. (2010, June 30). 'Nosaltres decidim, som una nació' será el lema de la marcha del 10 de julio ['Nosaltres decidim, som una was born' will be the motto of the march on July 10]. Retrieved July 02, 2020, from https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20100629/53954278364/nosaltres-decidim-som-una-nacio-sera-el-lema-de-la-marcha-del-10-de-julio.html.

Leerssen, J. (2015). The nation and the city: urban festivals and cultural mobilisation. Nations & Nationalism, 21(1), 2–20. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1111/nana.12090.

Llobera, J. (2004). Foundations of national identity: from Catalonia to Europe. Berghahn Books.

Martínez Celdrán, E., Fernández Planas, A. M., & Carrera Sabaté, J. (2003). “Castilian Spanish.” Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33(2): 255-259.

Maxwell, A, Turner, M. (2019). Nationalists rejecting statehood: Three case studies from Wales, Catalonia, and Slovakia. Nations and Nationalism. https://doi- org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1111/nana.12577.

McAndrew, M. (2013). Fragile Majorities and Education: Belgium, Catalonia, Northern Ireland, and Quebec. McGill-Queen’s Press.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Felibre. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/felibre.

Mount, I. (2015, May 23). Sport Is Politics For 73-Year-Old FC Barcelona Fan. Retrieved July 11, 2020, from https://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2015/05/23/fc-barcelona-fan-copa-del-rey.

Narotzky, S. (2019). Evidence Struggles: Legality, Legitimacy, and Social Mobilizations in the Catalan Political Conflict. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 26(1), 31-60.

Olle, J. (n.d.). Historical Flags. Retrieved on June 23, 2021, from https://www.angelfire.com/realm/jolle/.

Òmnium Cultural. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://www.omnium.cat/en/presentation/.

Phillips, W. D., & Phillips, C. R. (2010). A Concise History of Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&A N=490553&site=ehost-live.

Plataforma per la Llengua. (n.d.). The Catalan Language. Retrieved from https://www.plataforma-llengua.cat/media/upload/pdf/the-catalan-language_1494314945.pdf.

Rodriguez, V. (2019, September 18). Catalonia. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Catalonia.

Share, D. (1986). The Franquist Regime and the Dilemma of Succession. The Review of Politics, 48(4), 549-575. Retrieved July 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1407383.

Siguán, M. (1993). Multilingual Spain. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Sobrer, J. M. (2013, August 26). Catalan literature. Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/art/Catalan-literature.

Smithsonian Institution. (n.d.). Raimon: Catalonian Protest Songs. Retrieved June 21, 2020, from https://folkways.si.edu/raimon/catalonian-protest-songs/historical-song-struggle-protest-

world/music/album/smithsonian.

Solé Sabaté, J. (ed.). (2005). El Franquisme a Catalunya 1939-1977. I. La dictadura totalitària (1939-1945). [The Franco regime in Catalonia 1939-1977. I. The totalitarian dictatorship (1939-1945). Edicions 62.

Spanish language. (2020, June 30). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_language.

Stamp, A. (2017, September 28). Etxeberria's generous act shows just why Athletic Bilbao are “more than a club”. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from https://bleacherreport.com/articles/65670-etxeberrias-generous-act-shows-just-why-

athletic-bilbao-are-more-than-a-club.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (n.d.). Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.idescat.cat/.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (n.d.). Annual indicators. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10363&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2013, November 21). Knowledge of Catalan.

Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10363.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2014, May 22). Educational level of the population aged 16 years and over. By sex and age groups. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10368&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, August 27). Life expectancy at different ages.

Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10381&t=202000&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, July 17). Births and crude birth rate.

Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10342&t=202000&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, December 12). Deaths and crude death rate. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10344&t=202000&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, December 17). Infant and perinatal mortality rate. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10345&t=202000&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2021, March 19). GDP. By sectors. At current prices.

Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=aec&n=354&lang=en.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, December 23). Population on 1 January. By sex. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10328&lang=en&tema=xifpo&t=202000.

Strubell, M, Boix-Fuster, E, ed. (2011). Democratic Policies for Language Revitalisation: The Case of Catalan. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swan, M. (2001). Learner English: A Teacher’s Guide to Interference and Other Problems. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press.

Viladot, M. À. (2017, October 25). The current conflict between Spain and Catalonia explained.

Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://blog.oup.com/2017/10/spain-catalonia-

Vila i Moreno, F. Xavier. (2005). Barcelona (Catalonia): Language, Educationa and Ideology in an Integrationist Society. Language, Attitudes & Education in Multilingual Cities. Universa Press. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/11505968/Barcelona_Catalonia_Language_Education_and_Ideology_in_an_Integrationist_Society.

Wheeler, Max (2005). The Phonology of Catalan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woolard, K. (1989). Double Talk: Bilingualism and the Politics of Ethnicity in Catalonia. Stanford University Press.

Woolard, K. (2016). Singular and Plural. Ideologies of Linguistic Authority in 21st Century Catalonia. Oxford University Press.

Woolf, C. (2017, October 20). The roots of Catalonia’s differences with the rest of Spain.

Retrieved January 6, 2020, from https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-10-20/roots-catalonia-

World Bank. (n.d.). GDP (current US$) – Spain. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ES.

Images:

Brythones [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catalan_self-determination_referendum,_2014.svg

CC BY-SA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mes_que_un_club-FC_Barcelona.JPG

Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya [CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Artur_Mas_amb_Muriel_Casals,_presidenta_d%27%C3%92mnium._(4782755697).jpg

Ernest CS [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catalan_general_strike_2017.jpg

Galderich [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Felibres_anvers_horitzonal.jpg

Kuryakov, Y. (Linguist). (11 August, 2017). File:Romance-lg-classification- en.svg. Retrieved June 20, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Romance-lg- classification-en.svg#filelinks

Llapissera [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ramon_Pelegero.jpeg

LLs [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Protests_by_the_ruling_of_the_Judgment_to_the_leaders_of_the_Catalan_independentist_process.png

Longnon, A. (1876). File:Marca Hispanica Longnon 806.png. Retrieved June 25, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Marca_Hispanica_Longnon_806.png

Luis Barros [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Republicans_dressed_with_clothings_of_killed_clerics._Spanish_Civil_War.jpg

Motoroil [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Catalonia.svg.

Zarateman [CC0], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sant_Adri%C3%A0_de_Bes%C3%B2s__Placeta_Maci%C3%A0_2.jpg

Credits

Posted: 13 July 2021

Previous versions: March 2021

Contributing Analysts: W. B. Stallings

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina

![This photograph showcases a gathering of Renaixenca intellectuals and “felibres” (Provencal writers who sought to protect the Provencal language in France) in Montserrat in 1868 [“Felibres”, n.d.]. The Renaixença, or “Renaissance” in Catalan, was a literary movement that promoted the use of Catalan as a language and a culture. This was a revival of Catalan language usage and cultural espousal, which helped seed the roots for Catalan independence.](https://www.languageconflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Felibres_anvers_horitzonal-600x600.jpg)