Conflict Type

Peak Years

Intensity

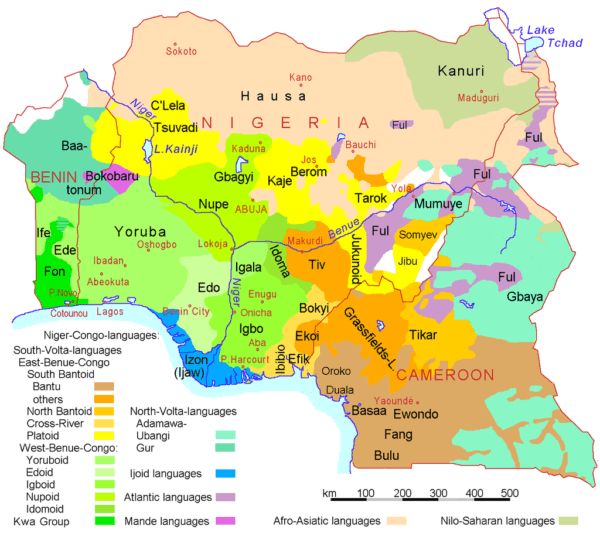

Prior to European colonization and mapping the borders of colonies, the various regions that comprise modern day Nigeria were quite separate with their linguistically distinct populations, and only connected through loose alliances and trade [The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019]. As a repurposed colonial language, English functions today as a bridge-language between the various groups, and while there is resentment towards its dominance, its use is necessary to keep Nigeria’s government and economy running. While facilitating inter-group function in a multilingual society, the dominance of this former colonial (and now global) language has deleterious effects on the health of regional languages and on the survival of smaller endangered ones. Setting English and its role in contemporary Nigeria aside, the other contemporary language conflicts that Nigeria has experienced can be usefully defined as competition for linguistic dominance, wherein ethnic groups (e.g. the Igbo) are contending for cultural and political control in their respective regions and against the intrusion of other ethnic groups (e.g. Hausa).

Historical Background

The Igbo people trace their history to the Nri Kingdom, established as early as the 9th century. It is believed that Eri, a sky-being sent by God, settled in Igboland in 948. According to oral tradition, the reign of the first Eze Nri (King of Nri) Ìfikuánim began in 1043, though this remains disputed by historians [Isichei, 2008].

Igbo political organization was republican and provided power to consultative assemblies of the people. The Umunna, a patrilineage system, dictated law and social order. Prior to European contact, the Igbo maintained a system of indentured servitude in which slaves had almost equal rights to masters [Agbasiere & Ardener, 2000]. In 1472, Portuguese explorers reached the Nigerian coast seeking trade opportunities. The Portuguese began a slave trade that would last from the 16th through 18th centuries and include both the Dutch and British. Slaves were typically sold to Europeans by the Aro Confederacy, a political union of the Aro people and an Igbo subgroup. In 1807, the slave trade was abolished, which shifted European focus towards industry and imperialism [Slattery, n.d.].

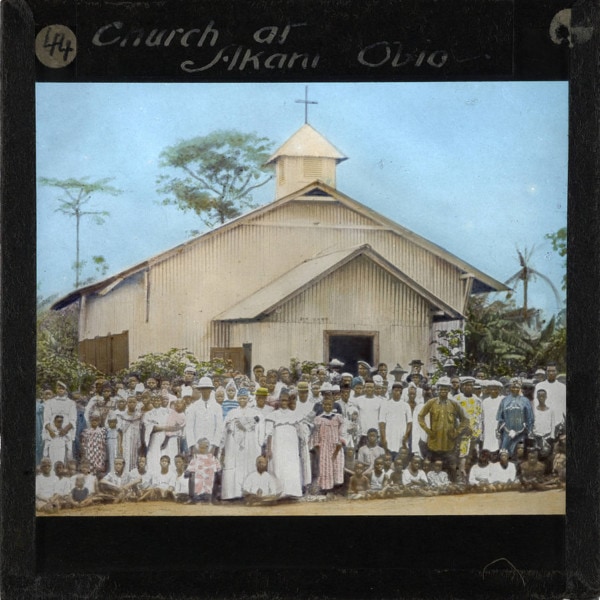

From 1850-1960, British colonization resulted in increased contact between the Igbo and their neighboring tribes along the Niger River, which led to a differentiation of Igbo ethnic identity from these surrounding neighbors. In response to European influence, the Igbo adopted Christianity and the Western education system, though some European models of centralization clashed with their traditions of decentralized government. In order to consolidate its power in Nigeria, the British government brought the various pre-colonial societies into a singular national identity [Bamgbose, 2009]. During this period, localized variation among the Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo declined, leading to each of these groups being more internally uniform, both linguistically and culturally. This leveling process within regions resulted then in the differences between each of the three groups and their regions becoming much more pronounced. Nigeria formally gained its independence from England in 1960 [Campbell, 2018].

Between 1966 and 1967, a series of ethnic conflicts occurred between the Muslim population and ethnic eastern Nigerians, including some Igbos, living in the north. The dispute began with the assassination of Nigerian military leader General Johnson Aguiya-Ironsi. The peace negotiations that followed led to the Biafra Civil War (1967-1970), in which the eastern Nigerian ethnic groups pushed to secede and establish the Republic of Biafra [Matthews, 2002]. The war resulted in several million casualties, discrimination against the Igbo people, and the reintegration of Biafra into Nigeria [Uzoigwe & Nwachuku, 2004]. Immediately following the war, the Igbo faced high unemployment and poverty rates. Over time, Igboland has recovered thanks in part to economic growth from the rise of the petroleum industry along the Niger Delta.

Rising Tensions in Northern Nigeria

In Nigeria’s Middle Belt, which separates the northern and southern regions of the country, clashes between herders and farmers killed 4000 people between 2011 and 2019; this is six times as many people as Boko Haram killed in the same period. These conflicts are coordinated efforts to uproot and destroy entire villages. The violence stems from herders, primarily Muslim members of the Fulani ethnic group, migrating onto lands traditional inhabited by Platoid speaking Christian farmers. This push has been caused by a combination of desertification and Boko Haram violence, and the conflict has been exacerbated by ethnic differences. While herders have moved their cattle across the Middle Belt before, they are now pushed further south in greater numbers. Issues such as cattle trampling a farmer’s fields are no longer seen as manageable or isolated, and as tensions rise, farmers have purposefully killed cattle and herders have deliberately ruined crops. New laws preventing the grazing of cattle in the open in some Nigerian states are seen as an attack by Fulani herders, who then have an increased presence in states without anti-grazing laws [O’Grady, 2018].

While the conflict is primarily a battle over resources, there remains an ethnic component as the Fulani and intruding into Benue-Congo and Hausa lands. In order to reduce violence, the current Nigerian president has allowed Hausa militia to assist in preventing outbreaks of violence. However, members of the militia have been accused of extortion, abduction, ransom demands, and murder; as a result, attacks by Fulani bandits have risen in retaliation [O’Grady, 2018]. Furthermore, as the president’s family has ties to the Fulani, the Hausa involved no longer fully support the Nigerian government. Many farmers no longer trust the president, who owns cattle himself, to find a balanced end to the conflict that does not unfairly benefit herders. As the death toll increases, all groups involved in the conflict are expressing disapproval for the government’s handling of the situation, with the lack of political authority and centralization recreating the original environment that gave rise to Boko Haram and indirectly caused this current crisis [International Crisis Group, 2018].

Biafra: Gone, Not Forgotten

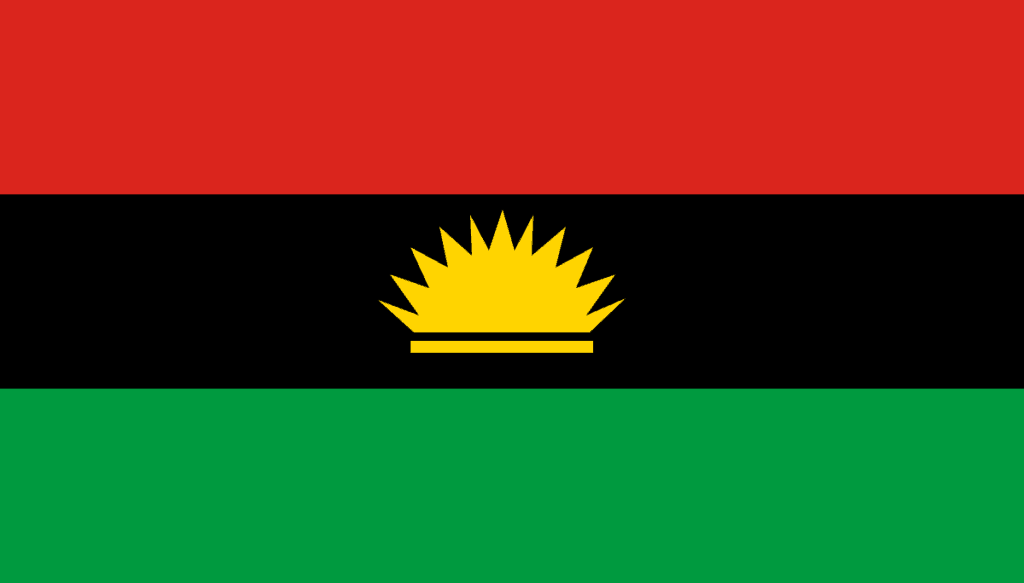

The flag of Biafra, a state primarily populated by Igbo which attempted to secede from Nigeria, sparking a 1967-1970 civil war which ended in Biafra’s defeat.

In the decade following its independence, Nigeria was torn apart by civil war that resulted from the Igbo state of Biafra attempting to secede from the rest of the country. Millions died in the subsequent violence and famine, weakening Igbo movements favoring secession and nationalism. However, there remains a small pro-Biafra movement among the Igbo, which was the target of government suppressions from August 2015 to August 2016 [BBC, 2016]. The Nigerian military reportedly shot over one hundred fifty civilians at a protest in support of Biafra in southeastern Nigeria, with video, photograph, and eyewitness evidence showing Nigerian military troops firing live ammunition into crowds, killing dozens of citizens with little to no warning. At least sixty people were shot over a two-day span coinciding with Biafra Remembrance Day, and it is believed the actual death toll is higher [Amnesty International, 2016].

The increase in state-sanctioned violence corresponds with the growing presence of Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB), a group promoting the return of Biafra as an independent state that was established in 2012. The group’s leader was arrested in late 2015, and members of the group have continued protesting at various pro-Biafra events in southern Nigeria. Outside of the Remembrance Day shootings, IPOB members have been targeted at events at schools and peaceful rallies, with reports of victims with execution-style gunshot wounds and mass graves of individuals taken by members of the military. Furthermore, firsthand accounts of beatings and torture carried out on detainees captured during pro-Biafra events indicate the Nigerian military is responsible for mistreating prisoners under their control. With little political or judicial oversight, it is unlikely further repressions of pro-Biafra protestors will cease in the future. Nigeria’s civil war may have ended in 1970, but support for a Biafran state remains strong nearly fifty years later [Amnesty International, 2016].

Stolen from their School: The Chibok Girls

In April 2014, insurgency group Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls from their school in Chibok, a small town in northern Nigeria [Beauchamp, 2014]. Boko Haram is an Islamist militant group aimed at establishing a caliphate in Nigeria, which is half Christian and half Muslim; these religious differences roughly correspond with ethnic divisions across the north and south regions of Nigeria. Seeking to implement strict Islamic laws, the group opposes the education of girls and has targeted a variety of non-Islamic institutions. The group’s leader threatened to sell the girls into slavery, leading outsiders to view the abductions as financially and religiously motivated. As of 2021, 112 of the 276 girls abducted are still missing [Busari, 2021].

The inability of the Nigerian government to find the kidnapped schoolgirls drew condemnation by internal and international groups and serves as an indication of the government’s weaknesses. Nigeria’s president at the time, Goodluck Jonathan, did not mention the abductions publicly for three weeks after they occurred, finally promising to return the girls safely in May 2014 before setting up a committee to find the abducted schoolgirls. Making the government’s response to this look even worse, Jonathan’s wife allegedly stated the kidnappings were falsified to make her husband’s administration look bad. Meanwhile, from 2014-2015 the Boko Haram kidnapped approximately two thousand women, many of whom were ransomed by the group. Public dissatisfaction with Jonathan’s actions during this crisis was at least partially responsible for his loss in Nigeria’s 2015 presidential elections. Meanwhile, while southern Nigeria is relatively unimpacted by Boko Haram, the Nigerian government’s inability to enforce regional borders or to provide basic services to its citizens in the northeast leave Boko Haram with a deep power base and the ability to avoid the Nigerian military, likely ensuring that their activity and internal violence will continue in coming years [Beauchamp, 2014].

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

- Genealogy/Relatedness

As over five hundred languages are spoken in Nigeria [Blench, 2014], a full exploration of the country’s linguistic background is difficult. This section will focus on majority languages that play the largest role in contemporary Nigerian politics and society outside of English: Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa.

Yoruba (Èdè Yorùbá) is spoken in Nigeria, Benin, and Togo as either first or second language, primarily by members of the Nigerian Yoruba ethnic group. Yoruba is mostly present in southwestern Nigeria, north of the capital city of Lagos. Igbo is spoken in the southeast, south of the confluence of the Niger and Benue Rivers, and Hausa dominates in the north of the country, centered around the northern city of Kano. Yoruba is a Kwa language, part of the Yoruboid group under the larger Niger-Congo language group and is most closely related to Itsekiri, which is spoken in the Niger Delta, and Igala, which is spoken in central Nigeria [Blench, 2014].

Igbo (Ásụ̀sụ̀ Ìgbò) is primarily spoken in southern Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea mostly by members of the Igbo ethnic group. The language is part of the Volta-Niger language branch, which, like Yoruba, is part of the larger Niger-Congo language family [Amadiume, 1996].

Hausa (Harshen/Halshen Hausa) is a member of the Chadic language family. It is spoken primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, and by the Hausa ethnic group that largely inhabits northern Nigeria and southern portions of the country Niger, which borders Nigeria to its north [Wolff, 2013].

- Phonetics/Phonology

Yoruba includes 18 consonants, among which are voiceless and voiced labial-velar stops /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/. Yoruba includes seven oral and five nasal vowels. It is also a tonal language with three significant lexical tones - high, middle, and low [Bamgboṣe, 1969].

Igbo includes 22 consonants but does not have a contrast between voiced stops and nasals. Igbo includes eight vowels, three of which are retracted tongue root (RTR)[1] vowels. It also features vowel harmony and nasal vowels. Similar to Yoruba, Igbo is a tonal language, with low and high lexical tones in most dialects [Ikekeonwu, 1999].

Hausa includes between 23 and 25 consonants depending on the dialect. There is a consonantal contrast between palatalized velars /c ɟ cʼ/, plain velars /k ɡ kʼ/, and labialized velars /kʷ ɡʷ kʷʼ/. Hausa also has glottalic consonants (implosives and ejectives) at different places of articulation depending on the dialect. Glottalic consonants require movement of the glottis during pronunciation and resemble a staccato sound. Hausa includes five vowels, which can be contrastively short or long. Similar to Yoruba and Igbo, Hausa is a tonal language with three lexical tones: low, high, and falling [Newman, 1996].

- Morphology and Grammar

Yoruba is an isolating language (i.e., a language where each morpheme represents a lexical or grammatical word and words are not themselves inflected). Basic word order is subject-verb-object (SVO) [Rowlands, 1969]. Although Yoruba has no grammatical gender, it maintains a noun class distinction between human and non-human nouns, which is evident in the use of different interrogative particles dependent on noun class: ta ni for human nouns (“who?”) and kí ni for non-human nouns (“what?”) [Ogunbowale, 1970].

Igbo has a rich derivational morphology but little inflection. Similar to Yoruba, it has no grammatical gender. Nouns are neither declined for case nor inflected for number, and there is no noun class system. However, personal pronouns are marked for person and number. They can be either dependent or independent.[2] Similar to Yoruba, Igbo is an SVO language [Uwalaka, 1997].

In contrast with Yoruba and Igbo, Hausa maintains masculine and feminine gender distinctions, except for the Zaria and Bauchi dialects spoken south of Kano [Caron, 2011]. Hausa, similar to other Chadic languages, has morphological complex pluralization patterns for nouns. Noun plurals in Hausa are derived using a variety of morphological processes, such as suffixation, infixation, reduplication, or a combination of any of these. There are 20 plural classes [Guzmán Naranjo & Becker, 2017]. Similarly to Yoruba and Igbo, basic word order in Hausa is SVO [Wolff, 2013].

- Lexicon and Vocabulary

Yoruba, centered as it is on the Lagos region, where the first British colony was established in Nigeria in 1851, has borrowed heavily from English since that time. Borrowing from English has continued, since English is the official language of the country and functions as a bridge language between all the others. Other languages that Yoruba has borrowed from significantly are Hausa, Arabic through Hausa, and French [Komolafe, 2014].

Hausa, until more recently, did not borrow heavily from English, Hausas living mostly in the north, away from the colonial activities of Britain. Hausa has borrowed from a variety of its neighboring African languages, including Berber (Afroasiatic), Fula, Mande, Yoruba (all Niger-Kordofanian), and Kanuri (Nilo-Saharan), and in so doing has set Hausa apart from other Chadic languages. Additionally, due to the influence of Islam, Hausa borrowed Arabic words from the fields of religion, commerce, law, government, horsemanship, scholarship, and literature [Jaggar, 2011].

Igbo borrowed words from English, Hausa, Yoruba, Efik and Igala as a result of contact with each of these. The English linguistic and cultural influence on Igbo through colonization was significant, leading to borrowing in the areas of education, technology, dressing, sports, names for disease, fauna and flora. Igbo also borrowed from Hausa and Yoruba because these three indigenous languages were and are in close contact, facilitated first by the British colonial regime and then by the Nigerian Government, as it sought to promote language planning and freedom of interaction among Nigeria’s three major ethnic groups. Igbo has also borrowed from Efik and Igala because they are geographical neighbors [Ajah, 2018].

- Orthography/Writing System

In the 17th century first attempts were made to promote Yoruba writing employed an Arabic script, ajami. From the mid-19th century, missionaries created a revised Latin alphabet to write Yoruba , with additional symbols added to indicate tone [Falola & Akintunde, 2016]. The current orthography of Yoruba includes the digraph ⟨gb⟩ and certain diacritics, including the underdots for the letters The diacritic underneath vowels indicates an open vowel, pronounced with the root of the tongue retracted ; ⟨ṣ⟩ stands for a postalveolar consonant [ʃ] like the English ⟨sh⟩. The Latin letters ⟨c⟩, ⟨q⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨x⟩, ⟨z⟩ are not used [Bamgboṣe, 1965b].1965b].

Before European colonization (in the 16th century), Igbo used nsibidi, a pictographic script, which turned obsolete when it became popular amongst secret societies such as the Ekpe, who used it as a secret form of communication [Oraka, 1983].

Before any official system of orthography for Igbo existed, travelers and writers documented Igbo sounds by utilizing the scripts of their own languages. Difficulties in transcribing certain sounds led to the use of the Standard Alphabet (1850s), published by a German philologist Karl Richard Lepsius. It contained 34 letters and included digraphs and diacritical marks to transcribe sounds distinct to African languages [Ohiri-Aniche, 2007].

The Lepsius orthography was replaced by the Practical Orthography of African Languages (1929) at the directive of the colonial government in Nigeria. It had 36 letters and disposed of diacritic marks but a number of controversial issues with the new orthography eventually led to its replacement by a standard Latin-based written form called Ọnwụ. in 1962. , Ọnwụ included 36 letters. In 1976, the Igbo Standardization Committee criticized the official (1962) orthography for its lack of accurate representation of tone and its inability to represent various sounds that are specific to certain Igbo dialects. A modified version of Ọnwụ was then developed, called the New Standard Orthography, which substituted ⟨[Oluikpe, 2014]. However, the New Standard Orthography has not been widely adopted again because it was felt by some to misrepresent certain sounds. In 2009 Ndebe script was created. The script gained popularity due to its logical approach to indicate tonal and dialectal variety, as compared to Latin letters [Ndebe, n.d.].

Hausa’s orthography is a Latin-based alphabet called boko, which was introduced and adapted for Hausa in the 1930s by the British colonial administration.[3]

Hausa has also been written in ajami, an Arabic alphabet, since the early 17th century [Omniglot, n.d.].

- Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

English is the official language of Nigeria, and is used to facilitate the cultural and linguistic unity of the country. French spoken in neighboring countries influenced the English spoken in the border regions of Nigeria. Additionally, French spoken in Nigeria may be mixed with some native languages. Indigenous languages remain the major languages of everyday communication in Nigeria as the majority of population lives in rural areas where they are spoken. Among them, Yoruba and Igbo are the most widely spoken. Nigerian Pidgin English is also a popular lingua franca and is widely spoken within the Niger Delta Region. Hausa is the most widely used indigenous language of Nigeria, due to the size of the Hausa ethnic group and to the historical use of Hausa as a preferred language for trade, which led to its adoption by various smaller ethnic groups [Adegbija, 2003].

Footnotes:

[1] Retracted Tongue Root (RTR) is the retraction of the base of the tongue in the pharynx during the pronunciation of a vowel, the opposite articulation of advanced tongue root [Ladefoged & Maddieson, 1996].

[2] The dependent pronouns include only singular pronouns and function as a single subject in combination with a main verb (e.g.,

bi ‘live’ (verb stem)

ebi m ‘I live’

i bi ‘you live’

o bi ‘he/she lives’

Note that for the first person singular, the m follows the verb stem.

The independent pronouns can be used as a subject, direct and indirect object (e.g.,

buru carry (verb stem)

anyï buru gï we carry you

unu buru mü you carry me

mü na gï buru ya me and you carry him

[3] The letter ƴ (y with a right hook) is used only in Niger; in Nigeria it is written ʼy.

Resources

“Ndebe,” https://ndebe.org/. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

ACCORD. Retrieved May 11, 2019, from https://www.accord.org.za/ajcr-

Adegbija, E. E. (2003). Multilingualism: A Nigerian Case Study. Africa World Press, p. 55. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Adetugbo, A. (1978). The Development of English In Nigeria Up to 1914: A Socio-Historical Appraisal. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 9(2), 89-103. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41857063

Afigbo, A. E. (1992). Groundwork of Igbo History. Lagos: Vista Books.

African Studies Institute, University of Georgia (2019). Yoruba Language. Yoruba People and Culture. Retrieved May 9, 2019 from http://www.africa.uga.edu/Yoruba/yorubabout.html.

Agbasiere, J. T., & Ardener, S. (2000). Women in Igbo Life and Thought. London: Routledge.

Ager, S. (2019). Hausa (Harshen Hausa / هَرْشَن هَوْسَ). Omniglot. Retrieved May 9, 2019

Ager, S. (2019). Igbo (Asụsụ Igbo). Omniglot. Retrieved May 10, 2019 from

Agriculture in Nigeria. (2021, 17 June). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Nigeria.

Ajah, C. (2018). Borrowing to Enrich Language Vocabulary: Lesson from the Igbo Language. Ebonyi Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 1(4), 151-173.

Amadi, S. (2007, January 10). Colonial Legacy, Elite Dissension and the Making of Genocide: The Story of Biafra. Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://items.ssrc.org/how-genocides-end/colonial-legacy-elite-dissension-and-the-making-of-genocide-the-story-of-biafra/

Amnesty International. (2016, November 24). Nigeria: At least 150 peaceful pro-Biafra activists killed in chilling crackdown. Retrieved May 11, 2019, from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/11/peaceful-pro-biafra-activists-killed-in-chilling-crackdown/.

Anthony, D. (2014). ‘Ours is a war of survival’: Biafra, Nigeria and arguments about genocide, 1966–70. Journal of Genocide Research, 16(2-3), 205-225. Retrieved from https://login.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=97586341&site=ehost-live.

Azuonye, Chukwuma, "Igbo as an Endangered Language" (2002). Africana Studies Faculty Publication Series. Paper 17. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.umb.edu/africana_faculty_pubs/17

Bamgboṣe, A. (1965b). Yoruba Orthography. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

Bamgboṣe, A. (1969). “Yoruba.” In Elizabeth Dunstan (ed.). Twelve Nigerian Languages. New York: Africana Publishing Corp, p. 166.

Bamgbose, J. (2009, May 26). Internally Displaced Persons: Case Studies of Nigeria’s Bomb Blast and the Yoruba-Hausa Ethnic Conflict in Lagos, Nigeria. The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/541.

BBC. (2016, November 24). Nigeria security forces 'killed 150 peaceful pro-Biafra

Beauchamp, Z. (2015, May 12). Boko Haram's kidnapping of 276 girls and its aftermath,

Bernhardt, A., & Rennebohm, M. (2010, April 10). Igbo Women Campaign for Rights. Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/igbo-women-campaign-rights-womens-war-nigeria-1929

Blackburn, R. (2010). The Making of New World Slavery. London: Verso.

Blench, R. (2014). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages. Oxford: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

Bocquené, H., & Ndoudi, O. (2002). Memoirs of a Mbororo: The Life of Ndudi Umaru, Fulani Nomad of Cameroon. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Busari, S. [2021, January 29]. Several remaining missing Chibok schoolgirls escape from Boko Haram. CNN. Retrieved June 14, 2021, from: https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/29/africa/nigeria-chibok-girls-escape-intl/index.html.

Campbell, J. (2018, January 2). Lord Lugard Created Nigeria 104 Years Ago. Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://www.cfr.org/blog/lord-lugard-created-nigeria-104-years-ago.

Canci, H., & Odukoya, O. A. (2016, August 29). Ethnic and religious crises in Nigeria –

Caron, B. (2011). Hausa Grammatical Sketch. Paris: LLACAN.

Catholicism in Nigeria. (n.d.). Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://rpl.hds.harvard.edu/faq/catholicism-nigeria.

Chambers, D. B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier Igbo Africans in Virginia. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Chigere, N. H. (2001). Foreign Missionary Background and Indigenous Evangelization in Igboland. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster.

Chuku, G. (2016). Igbo Women and Economic Transformation in Southeastern Nigeria, 1900-1960. London: Routledge.

conflict-is-proving-deadlier-than-boko-haram/94040.

Conley-Zilkic, B., & De Waal, A. (2014). Setting the Agenda for Evidence-Based Research on Ending Mass Atrocities. Journal of Genocide Research, 16(1), 55-76. Retrieved from https://login.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=94419804&site=ehost-live.

Daniel-Kalio, B. (2018). Historical Analysis of Educational Policies in Nigeria: Trends and Implications. International Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 11(2), 247-264. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277066757_Historical_Analysis_Of_Educational_Policy_Formulation_In_Nigeria_Implications_For_Educational_Planning_And_Policy.

Danladi, S. S. (2013). Language Policy: Nigeria and the Role of English Language in the 21st Century. European Scientific Journal, 9(17), 1-21. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/328023643.pdf.

Diamond, S. (1967). The Biafra Secession. Africa Today, 14(3), 1-2. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4184781

Ekechi, F. K. (1972). Missionary Enterprise and Rivalry in Igboland 1857-1914. London: Frank Cass and Company Limited.

Equiano, O. (1837). The Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Boston: Issac Knapp. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm.

Explained. Vox. Retrieved May 11, 2019 from

Falola, T., & Akinyemi, A. (2016). Encyclopedia of the Yoruba. Indiana University Press, p. 194.

Fāsī, M., & Hrbek, I. (1995). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh century. Oxford: Heinemann Educational.

from https://www.omniglot.com/writing/hausa.htm.

Furniss, G. (2010). Power, Marginality and African Oral Literature. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Gould, M. (2013). The Biafran War: The Struggle for Modern Nigeria. London: I.B. Tauris.

Guzmán Naranjo, M., & Becker, L. (2017). Quantitative Methods in African Linguistics - Predicting Plurals in Hausa. ACAL 48. Indiana, USA.

Heerten, L., & Moses, A. D. (2014). The Nigeria–Biafra War: Postcolonial Conflict and the Question of Genocide. Journal of Genocide Research, 16(2-3), 169-203. Retrieved from https://login.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=97586340&site=ehost-live.

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00fwp/igbo/igbohistory.html.

https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/558/ling.wp.v6.n1.paper8

https://www.everyculture.com/wc/Mauritania-to-Nigeria/Hausa.html.

https://www.omniglot.com/writing/igbo.htm.

https://www.vox.com/2014/5/12/18076900/nigeria-kidnapping.

Ikekeonwu, C. (1999). “Igbo.” Handbook of the International Phonetic Association.

Ilogu, E. (1979). Christianity and Igbo Culture. Brill Archive.

International Crisis Group. [2018, July 26]. Stopping Nigeria’s Spiraling Farmer-Herder Violence. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/262-stopping-nigerias-spiralling-farmer-herder-violence.

Isichei, E. (2008). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge Univ. Press.

issues/ethnic-religious-crises-nigeria/.

Jaggar, P. (2011). The Role of Comparative/Historical Linguistics in Reconstructing the Past: What Borrowed and Inherited Words Tell us about the Early History of Hausa, 1-17.

Keil, C. (1970). The Price of Nigerian Victory. Africa Today, 17(1), 1-3. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4185054

Komolafe, O. E. (2014). Borrowing Devices in Yoruba Terminography. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(8), 49-55.

Ladefoged, P., & Maddieson I. (1996). The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Blackwell.

Legner, E. F.. (n.d.). The Igbo of Nigeria. (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2019, from http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~legneref/igbo/igbo2.htm.

Lovejoy, P. E. (2009). Identity in the Shadow of Slavery. London: Continuum.

Marley, D. (1985). Reales asientos y licencias para la introducción de esclavos negros a la América Española (1676-1789). Windsor: Rolston-Bain.

Mathews, M. P. (2002). Nigeria: Current Issues and Historical Background. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

N.A., (2019). Hausa. Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved May 9, 2019 from

Ndukaihe, V. E., & Fonk, P. (2008). Achievement as Value in the Igbo/African Identity: The Ethics. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster.

Newman, P. (1996). “Hausa Phonology.” In Kaye, Alan S.; Daniels, Peter T. (eds.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa. Eisenbrauns, pp. 537–552.

Nigeria Profile - Timeline. (2019, February 18). Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13951696 .

Nigeria: Civil War. (2015, August 7). Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2015/08/07/nigeria-civil-war/

Nigeria: Constitution Development History. (n.d.). Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://lawnigeria.com/2018/03/nigeria-constitution-development-history-and-legal-complex/

Office of International Religious Freedom (2018). 2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Nigeria. US Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-report-on-international-religious-freedom/nigeria/.

O'Grady, S. (2018, July 26). This little-known conflict in Nigeria is now deadlier than Boko Haram. Washington Post. Retrieved May 11, 2019 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/ worldviews/wp/2018/07/26/this-little-known-conflict-in-nigeria-is-now-deadlier-

Ogunbowale, P. O. (1970). The Essentials of the Yoruba Language. University of London Press: London.

Ohiri-Aniche, Chinyere (2007). “Stemming the tide of centrifugal forces in Igbo orthography.” Dialectical Anthropology, 31(4), 423–436.

Okereska, O. P., PhD. (2015). Evolution of Constitutional Government in Nigeria: Its Implementation National Cohesion. Global Journal of Political Science and Administration, 3(5), 1-8. Retrieved from https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Evolution-of-Constitutional-Government-in-Nigeria-Its-Implementation-National-Cohesion.pdf.

Okolo, B. A. (1981). The History of Nigerian Linguistics: A Preliminary Survey. Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, 6, 99-126. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from

Oluikpe, E. N. (2014). “Igbo language research: Yesterday and today.” Language Matters, 45(1), 110–126.

Omniglot. “Hausa,” https://omniglot.com/writing/hausa.htm. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

Onwuejeogwu, M. A. (1981). An Igbo Civilization. London: Ethnographica.

Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co. pp. 17, 13.

Paddock, A. (2018, July 19). Women's War of 1929. Retrieved May 14, 2019, from https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-271

Pritchett, F. (2006). A History of the Igbo Language. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from

protesters'. Retrieved May 11, 2019 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-

Rowlands, E. C. (1969). Teach Yourself Yoruba. English Universities Press: London.

Rubin, N. N., & Cotran, E. (1970). Annual Survey of African Law 1967 (Vol. 1). Taylor and Francis Group.

Shillington, K. (2005). Encyclopedia of African History. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. Retrieved from https://search-credoreference-com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/content/title/routafricanhistory?tab=entries.

Slattery, K. (n.d.). The Igbo People - Origins and History. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~legneref/igbo/igbo1.htm

Sunday, O. (2019, May 5). This Nigerian Conflict Is Proving Deadlier Than Boko Haram. Retrieved May 11, 2019, from https://www.ozy.com/fast-forward/this-nigerian-

than-boko-haram/?utm_term=.3422de38f4bd.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019). Hausa States. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Hausa-states.

Uchendu, V. C. (1965). The Igbo of Southeast Nigeria. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Uwalaka, M. A. (1997). Igbo Grammar. The Pen Services.

Uzoigwe, G. N., & Nwachuku, L. A. (2004). Troubled Journey: Nigeria Since the Civil War. University Press of America.

Wolff, H. E. (2013). “Hausa language.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hausa-language. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

Image Credits

Aba Women of Nigeria. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1900s). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aba_Women_of_Nigeria_(early_20th_century).jpg.

Chinua Achebe. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2008, September 25). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinua_Achebe_-_Buffalo_25Sep2008.jpg.

Church of Akani Obio. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (circa 1880). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22Church_of_Akani_Obio%22,_late_19th_century_(imp-cswc-GB-237-CSWC47-LS2-044).jpg.

Flag of Biafra. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2005, October 24). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Biafra.svg.

Herds Man. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2017, November 26). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herds_man.jpg.

Lord Lugard. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1880-1886). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lord_Lugard.jpg.

Nigeria Flag. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1960, October 1). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nigeria_Flag.svg.

Nigeria Linguistic 1979. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nigeria_linguistic_1979.jpg.

Olaudah Equiano – The Iinteresting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1789). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olaudah_Equiano_-_The_interesting_Narrative_of_the_Life_of_Olaudah_Equiano_(1789),_frontispiece_-_BL.jpg.

Oliver Lyttelton Visc Chandos. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1941, July 8). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oliver_Lyttelton_Visc_Chandos.jpg.

Parents of Chibok kidnapping victims. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2014, April 28). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parents_of_ Chibok_kidnapping_victims.png.

Starved Girl. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1960s). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Starved_girl.jpg.

The Treaty of Utrecht. [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2010, November 13). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Treaty_of_Utrecht_(clean).jpg.

Credits

Posted: 10 July 2021

Previous versions: August 2020

Contributing Analysts: Jill Boggs, Madison Bradley

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina