The conflict between Okinawan and Japanese languages hinges on the problem of definition. The current Japanese government views the conflict as an intralingual issue, since they claim Okinawan is a mere dialect of Japanese. The Okinawan people see their language as distinct from Japanese and have since the 19th century. Therefore, they view the language dispute as a geo-political minority conflict. In 1879, the Ryūkyūan islands were annexed and became a Japanese prefecture. Standardization efforts began with the promotion of second language education, with “Okinawa Conversation” – a bilingual Okinawan-Japanese textbook – used in all schools by 1880 [Heinrich, 2005]. The 1907 Ordinance to Regulate the Dialect enforced the sole use of Standard Japanese in schools and public offices, wherein schoolchildren were taught to monitor and enforce language use between their peers [Heinrich, 2005]. With the 1931 Movement for the Enforcement of the Standard Language, attempts to enforce Standard Japanese entered all forms of Ryūkyūan society [Heinrich, 2005]. While Japan has stopped actively suppressing the language, most native Okinawan speakers today are elderly, and many of the current generation cannot understand it at all. Some younger people are attempting to revitalize their language, but Okinawan, along with the other Ryukyuan languages, is slowly dying out.

Historical Background

The Ryūkyūan people are the indigenous peoples of the Ryūkyūan Archipelago, an arc of 55 islands stretching over 650 miles from Kyūshū, Japan to Taiwan. The origins of the contemporary Ryūkyūan people are debated due to genetic differences with the people of mainland Japan [Yamaguchi-Kabata, 2008]. Some believe they are ancestors of the Jōmon, who are thought to have migrated from continental Eurasia between 15,000 B.C.E. and 1,000 B.C.E. The migration of the Jōmon to the Japanese Archipelago was the first major human migration to these areas [Hanihara, 1991]. The second major human migration occurred during the Yayoi Period, from around 800 B.C.E. to 250 C.E. During this time the Yayoi people, originating from China and Korea, intermingled with the Jōmon people already inhabiting the region [Hanihara, 1991]. DNA analysis has shown that the migration of the Yayoi had a much greater impact on the genetics of the modern-day native Mainland Japanese population than it did on the modern-day native Ryūkyūan population [Yamaguchi-Kabata, 2008]. This suggests fewer Yayoi people migrated to the Ryūkyū Islands than to the Japanese Mainland. Several centuries of isolation from the geographically distant Japanese Mainland led the Ryūkyūan people to develop their own distinct cultures and languages.

Since the initial unification of the Ryūkyū Islands under the first Shō Dynasty in 1416, Japan has had a large influence on the islands. In 1609, the Shimazu daimyo, a vassal of the Tokugawa Shogunate (the government of Mainland Japan during this period) successfully invaded, and the islands became subject to Tokugawa (Japanese) laws and edicts, which included participating in Japan’s national census and ending the sovereignty of the Ryūkyūan Kingdom [Bremen and Shimizu, 2013]. The Mainland Japanese government allowed the Ryūkyū Islands to keep their monarchy, but they stripped the Ryūkyūan king of any power to protest their policies or decisions. In 1879, the Japanese government officially annexed the Ryūkyū Islands and established the Okinawa Prefecture, the Japanese territory that consists of most of the Ryūkyūan Archipelago [Bremen and Shimizu, 2013]. Not long after the Ryūkyū Islands were incorporated as part of Japan, the Japanese government began centralizing control over language policy throughout its territory. Ryūkyūan languages were included in the category of dialects of Japanese that needed to be standardized.

In the late 19th to early 20th century, the Japanese government established a national standard variety of the Japanese language, Tōkyō-go, derived from the Tokyo dialect spoken by Japan’s upper class. Japan’s ruling elite believed that language standardization would build national unity, help to modernize Japan, and contribute to its long-term success [Twine, 1988]. Along with the policy of language standardization, the Japanese government widely promoted the false idea that the Ryūkyūan languages were dialects of Japanese, rather than distinct languages [Heinrich and Ishihara, 2017]. This allowed the Japanese government to claim that they were merely correcting the grammar and pronunciations of the “inferior” dialects of Japanese spoken by the Ryūkyūans. It also allowed the Japanese government to promote an image, supported by Japan’s foundational myths, of Japan as a mono-lingual and mono-cultural society, erasing the distinct languages of the Ryūkyū Islands by suppressing their use in schools and public places [Heinrich, 2005]. Important policies include the 1907 Ordinance to Regulate Dialects, which forbid children from speaking their native Ryūkyūan languages in schools, the use of dialect tags to mark and shame students who were caught speaking in a Ryūkyūan language, and a 1939 law which made it illegal to speak in a Ryūkyūan language at any government office [Heinrich, 2005].

From April 1 to June 21, 1945, U.S. and Japanese forces fought in the Battle of Okinawa on the largest of the Ryūkyū Island chain. After several weeks of intense fighting that left 12,000 American soldiers, 110,000 Japanese troops, and upwards of 150,000 Okinawan civilians (out of a population of 300,000) dead, U.S. forces captured the island and gained control of most of the Ryūkyūan Archipelago [Mitchell, 2015]. Japan’s defeat at the Battle of Okinawa marked the beginning of U.S. military occupation and eventual administrative control over the Ryūkyū Islands. The U.S. occupation created oppressive conditions for the Ryūkyūan people, including the widespread practice of land confiscation. These conditions led a large portion of the Ryūkyūan population to resent American occupation and long to reunite with Mainland Japan, though some Ryūkyūan people wanted to become independent from both countries [Heinrich, 2004]. As a result, organizations and movements were established on the Ryūkyū Islands that promoted Japanese nationalism and advocated for reunification with Japan. In keeping with these reunification movements, local governments on the Ryūkyū Islands re-enforced the language suppression policies that had occurred under Japanese rule.

In 1972, the Okinawa Reversion Agreement went into effect, handing control of the Ryūkyū Islands back to Japan [Heinrich, 2004]. Since this point, the decline of the Ryūkyūan languages has continued unabated. Today, all Ryūkyūan languages are designated as either “definitely endangered” or “severely endangered” in UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger [Moseley, 2010]. Obstacles to a revival of the Ryūkyūan languages include the Japanese government’s refusal to recognize the Ryūkyūan people as a distinct minority and a lack of programs to educate Ryūkyūan children in their native languages.

The American occupation

Between 1945 and 1951, during the early U.S. occupation of the Ryūkyū Islands, American authorities sought to promote Ryūkyūan languages and culture. American officials placed a ban on the use of teaching materials from Mainland Japan and attempted to create school textbooks in Ryūkyūan languages. Despite these efforts and the lack of Mainland Japanese government pressure, organizations such as the Okinawan Teachers Association promoted the use of Standard Japanese in schools and continued many of the former Japanese government's language suppression policies, and in 1951 Japanese textbooks were once again imported [Heinrich, 2004].

The attempts by U.S. officials to reverse the suppression of the Ryūkyūan languages was doubly counterproductive. First, many of the Ryūkyūan people were suspicious of the motives of the United States in establishing these programs to promote Ryūkyūan language and culture. A widely held theory within Ryūkyūan community was that the United States sought to promote Ryūkyūan languages and culture in order to weaken the Ryūkyūan people’s loyalty to and their cultural and linguistic connection with the Japanese Mainland [Heinrich, 2004]. A damaged connection would make it less likely that people would advocate for reincorporation with Japan, legitimizing American control of the strategically important Ryūkyū Islands. Second, the U.S. occupation of the Ryūkyū Islands created unfavorable conditions, including the extensive military infrastructure, land confiscation, and prostitution, that led many in the Ryūkyūan community to resent the American administrative control of the islands and prefer reunification with Mainland Japan [Heinrich, 2004]. In response to these popular attitudes, several Japanese Nationalist movements developed, including the Movement for Return to the Fatherland, which advocated for the Standard Japanese language to be spoken throughout the Ryūkyū Islands. Thus, Ryūkyūans who chose to speak Standard Japanese over their native language did so to protest the U.S. occupation and to signal their desire for the Ryūkyū Islands to be reunited with Mainland Japan. This sentiment, created in part by U.S.’ efforts to promote the indigenous languages and culture, devitalized the Ryūkyūan languages. Under the American administrative control of the Ryūkyū Archipelago, a significant generational gap in Ryūkyūan language abilities developed. A majority of the Ryūkyūan population born after 1950 were unable to speak their native languages.

Reviving Uchinaguchi

Nearly all Okinawans under the age of sixty can neither speak nor understand Okinawan. Bairon Fija, an activist, local radio DJ, and teacher, is an exception. Feeling that it is his cultural duty as an Okinawan, Fija attempts to revive the use of the language among younger generations [Tomita, 2015].

Born in 1969 to an Okinawan mother and an American father who he never knew, Fija struggled with his identity as a child in the 1970s— he appeared white, and like most young Okinawans attended Japanese schools and did not learn Okinawan. In 1993, at the age of twenty-four, he heard the sanshin (a traditional Okinawan stringed instrument) for the first time. This experience caused him to fall in love with the Okinawan culture, and he made it his mission to learn the Okinawan language, which he refers to as Uchinaguchi (its traditional name). While he previously used the last name Higa, a Japanese name, he now uses the authentic Okinawan pronunciation:“Fija.” Fija’s embrace of his Okinawan culture began his passion to promote the Uchinaguchi language to younger generations of Okinawans [Tomita, 2015].

Moe Yonamine

The Japanese government used education policies in their campaign to suppress the Ryūkyūan languages. The experiences of Moe Yonamine, author and editor of Rethinking Schools magazine, as a young woman in the 1980s and 1990s provide an illustration of the personal impacts of such policies. Moe was born on the island of Okinawa, the largest of the Ryūkyū Islands, to a native Okinawan family. Moe’s family moved to the United States in 1985 when Moe was age 7. In 1991, at age 13, Moe and her family returned to Okinawa. Because she had grown up in the United States, she was unaware that her native language was all but forbidden in her old home [Yonamine 2017].

Shortly after she and her family returned to Okinawa, Moe began to attend school. One day during class, Moe spoke in Uchinaaguchi, her native language and one of the indigenous languages of Okinawa. Her teacher struck her in the head. Moe fell to the floor and the teacher yelled at her, “Don’t you talk that dirty language!” Utterly bewildered at what had just happened, Moe stood up, walked out the school, and went home.

When she got home, Moe told her family what happened. After she finished, Moe’s grandfather offered her advice. He and his family, like all Okinawans, had been caught in the crossfire of U.S. and Japanese forces during the Battle of Okinawa. After he witnessed the large-scale destruction and death, including that of several close friends, caused by the battle he made a promise to himself, which he also shared with Moe. “Don’t let anyone make you forget who you are” [Yonamine 2017]

Moe’s story is not unique among the Ryūkyūan youth. Mainland Japanese, and later local Ryūkyūan officials, implemented policies designed to shame and punish Ryūkyūan children for speaking their native languages at school. In addition, Moe describes how education on the island of Okinawa emphasized Japanese language and culture, driving Ryūkyūan heritage out of the curriculum. The combination of public shaming and a lack of Ryukyuan language and cultural education were designed to make the Okinawan youth forget their heritage and to root out any cultural identity not tied to Mainland Japan. The success of these policies is shown in the attitudes that of many of Moe’s friends have towards their Ryukyuan heritage. They tell her that they wish their skin was lighter and that they could speak Japanese without an Okinawan accent. They tell her they will make sure that their children speak without an “island accent”. They wish to forget their heritage. Moe believes that to forget is to lose a part of themselves, and to lose their connection to a beautiful community, united by a shared language and culture formed over thousands of years [Yonamine 2017].

Just as education was used to make the Okinawan children forget their heritage, Moe argues education can be used to preserve the Okinawan language and culture. If the youth of Okinawa are taught about their native languages and culture in school, the Okinawan community can ensure that their heritage is not forgotten nor felt as if it is something to be ashamed of. Yonamine writes, “My language is not dirty. My language is powerful. Kanasasoulmn, Uchinaaguchi, the language of my heart.”

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

- Genealogy/Relatedness

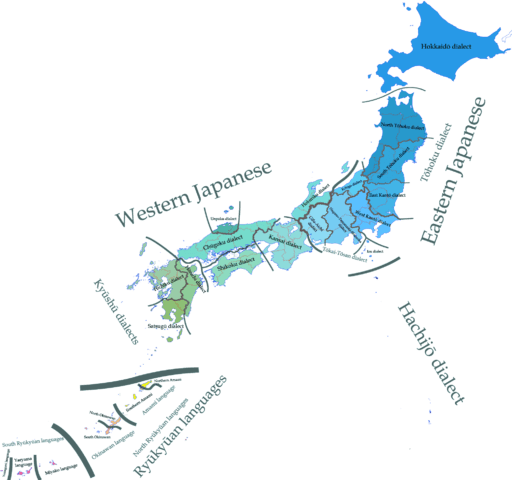

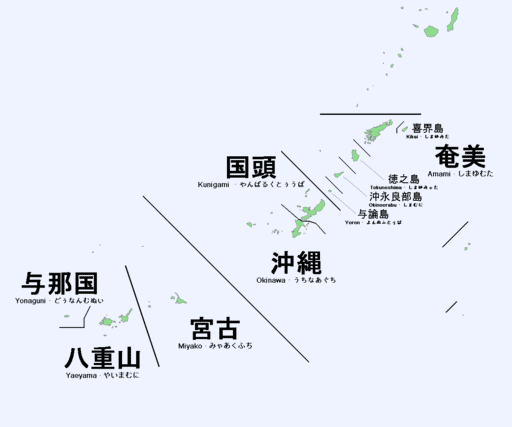

The Ryūkyūan languages are the languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the southern part of the Japanese archipelago. Other names used for the Ryūkyūan languages are Ryūkyū-goha, Ryūkyū-shogo in Ryukyuan, Shima kutuba, literally “Island Speech,” also Lewchewan languages. There are four major island groups which make up the Ryukyu Islands: the Amami Islands (Kagoshima Prefecture), the Okinawa Islands, the Miyako Islands, and the Yaeyama Islands (Okinawa Prefecture) [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010].

Figure 1. The Ryūkyūan languages map

Table 1. Northern and Southern Ryūkyūan languages[1]

| Language | Local name | Geographic distribution | Speakers | Standard dialect | ISO 639-3 |

| Northern Ryūkyūan languages | |||||

| Kikai | Shimayumita | Kikaijima | 13,000 | N/A | kzg |

| Amami | Shimayumuta | Amami Ōshima and surrounding minor islands | 12,000 | Setouchi, | ams, ryn |

| Tokunoshima | Shimayumiita | Tokunoshima | 5,100 | Tokunoshima | tkn |

| Okinoerabu | Shimamuni | Okinoerabujima | 3,200 | N/A | okn |

| Yoron | Yunnu Futuba | Yoronjima | 950 | Yoron | yox |

| Kunigami | Yanbaru Kutūba | Northern Okinawa Island (Yanbaru region), and surrounding minor islands | 5,000 | Largest community is Nago | xug |

| Okinawan | Uchināguchi | Central and southern Okinawa Island and surrounding minor islands | 980,000 | Traditionally Shuri, modern Naha | ryu |

| Southern Ryūkyūan languages | |||||

| Miyako | Myākufutsu Sumafutsu | Miyako Islands | 68,000 | Hirara | mvi |

| Yaeyama | Yaimamuni | Yaeyama Islands (except Yonaguni) | 47,600 | Ishigaki | rys |

| Yonaguni | Dunan Munui | Yonaguni Island | 400 | Yonaguni | yoi |

Like the Japanese language, the Ryūkyūan languages are a part of the Japonic language family. The languages are not mutually intelligible with each other. The Okinawan language, one of the more known Ryūkyūan languages, is only 71% lexically similar to standard Japanese [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010].

According to some historical accounts, Proto-Japonic speakers populated the Ryukyu Islands in the first millennium. Relative isolation allowed the Ryukyuan languages to separate from Proto-Japonic spoken in Mainland Japan (later known as Old Japanese). However, other historical accounts suggest that the Ryukyuan languages evolved from a “pre-Proto-Japonic language” from the Korean peninsula [Heinrich et al., 2015].

After the initial settlement of the Ryukyu Islands, there was little contact between the main islands and the Ryukyu Islands for centuries, allowing Ryūkyūan and Japanese to diverge significantly from each other. In the 17th century the Kyushu-based Satsuma Domain conquered the Ryukyu Islands [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010]. The Ryukyu Kingdom remained autonomous until 1879, when it was annexed by Japan [Takara, 2007].

- Phonetics/Phonology

The Ryūkyūan languages often share some phonological features with Japanese, including a voicing opposition for obstruents, CV(C) syllable structure, moraic rhythm, and pitch accent. However, many Ryūkyūan languages also differ from Japanese [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010].

A notable consonantal distinction is represented by glottalic consonants. Such that, the Northern Ryūkyūan languages (Okinawan, among others) include glottalic consonants, whereas the Southern Ryūkyūan languages have little to no glottalization [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010].

The phonology of Japanese includes 15 consonants, whereas Okinawan includes 20 consonants. The two consonant systems are relatively similar, but Okinawan retains the labialized consonants /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ which were lost in Late Middle Japanese, includes a glottal stop /ʔ/, a voiceless bilabial fricative /ɸ/ distinct from the aspirate /h/, and two different affricates. Additionally, Okinawan lacks the major allophones [t͡s] and [d͡z] found in Japanese [Akamatsu, 2000].

Vowels also vary in number and contrast in the Ryūkyūan languages. For example, Amami (a Northern Ryūkyūan language) includes high and mid central vowels, whereas Yonaguni (a Southern Ryūkyūan language) only has three contrasting vowels, /i/, /u/ and /a/. Japanese has a typical five-vowel system of /a, i, u, e, o/, which is identical to the Okinawan language. In Japanese and Okinawan all vowels have a phonemic length contrast and may be long or short [Heinrich et al., 2015].

- Morphology and Grammar

The Ryūkyūan languages are generally SOV (subject-object-verb) order, dependent-marking, modifier-head, nominative-accusative languages, similar to Japanese. Adjectives are usually found in a form of bound morphemes and occur either with noun compounding or using verbalization, also similar to Japanese. Many Ryūkyūan languages mark both nominatives and genitives using the same marker, which depends on an animacy hierarchy, which is a grammatical feature marking how alive the referent of a noun is. For example, Japanese uses animacy in a form of two existential/possessive verbs: one for animate nouns (humans and animals) and one for inanimate nouns (non-living objects and plants). The Ryūkyūan languages have topic and focus markers, which differ depending on the sentential context. Ryūkyūan also preserves a verbal inflection for clauses with focus markers, a feature found in Old Japanese, but lost in Modern Japanese [Shimoji & Pellard, 2010].

- Lexicon and Vocabulary

Ryūkyūan and Japanese split before the 8th c. CE. However, Ryūkyūan exhibits some features, like borrowings from Middle Japanese, suggest close contact with Japanese until a recent date. Similarities exist between Ryūkyūan and the Kyūshū dialects (i.e., the Japanese dialects of the southernmost Japanese island) [Serafim, 2003]. A common vocabulary for agriculture, pottery and metallurgy suggests that Proto-Ryūkyūan speakers were likely farmers [Pellard, 2011].

- Orthography/Writing System

Historically, classical Chinese writing known as Kanbun (i.e., using traditional Chinese characters) was used in official documents in the Ryūkyūan languages, while informal materials, such as poetry and songs, were often written in the hiragana in the Shuri dialect of Okinawan. When Okinawan was the official language of the Ryūkyū Kingdom (1429-1879), documents were written in kanji and hiragana, derived from Japan. Today, the Ryūkyūan languages are not often written and there are no standard orthographies. When the Ryūkyūan languages are written, Japanese characters are used.

- Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

Today’s official position of the Japanese government labels Okinawan a dialect of Japanese. The policy of assimilation (i.e., one people, one language, one nation), and increased interaction between Japan and Okinawa Prefecture has led to the development of Okinawan Japanese (not the same as Okinawan), a dialect of Japanese influenced by the Okinawan and Kunigami languages. Consequently, a wider use of Standard Japanese and Okinawan Japanese has led to the Ryūkyūan languages becoming endangered [Unesco.org].

One sociolinguistic factor that influenced the endangerment of the Ryūkyūan languages was a policy of “dialect tags” in the 20th century, when schools punished the students who spoke in Okinawan [Heinrich, 2005]. Since then, several revitalization efforts were attempted to reverse the language shift. However, education in Okinawa is conducted exclusively in Japanese, and children do not learn Okinawan as their second language. As a result, at least two generations of Okinawans have grown up without any proficiency in their local languages both at home and school [Heinrich et al., 2015].

[1] The table adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages

Resources

Akamatsu, Tsutomu. (2000). Japanese Phonology: A Functional Approach, München: Lincom Europa.

Anderson, M. (2009, March). Emergent Language Shift in Okinawa. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329655962_Emergent_Language_Shift_in_Okinawa.

Bairon, F., Brenzinger, M., & Heinrich, P. (2009). The Ryukyus and the New, But Endangered, Languages of Japan. Asia Pacific Journal, 7, 19(2), 1–21. Retrieved from https://apjjf.org/-Patrick-Heinrich/3138/article.html.

Bairon, F., Heinrich, P. (2007). “Wanne Uchinanchu – I am Okinawan.” Japan, the US and Okinawas Endangered Languages.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 5(11). Retrieved from https://apjjf.org/-Patrick-Heinrich/2586/article.html.

Barclay, K. (2006). Between Modernity and Primitivity: Okinawan Identity in Relation to Japan and the South Pacific. Nations and Nationalism, 12(1), 120. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2006.00233.x.

Battle of Okinawa. (2019). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Battle-of-Okinawa.

Braibanti, R. (1954). The Ryukyu Islands: Pawn of the Pacific. The American Political Science Review, 48(4), 972-998. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1951006?seq=7#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Bremen, J. V., Shimizu, A. (1998). Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia: Comparative and Historical Colonialism. London, U.K.: Routledge.

Davies, W.D., & Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights: Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Elmendorf, W. (1965). Impressions of Ryukyuan-Japanese Diversity. Anthropological Linguistics, 7(3), 1-3. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30022494.

Fifield, A. (2014, November 29). In Japan’s Okinawa, Saving Indigenous Languages is About More than Words. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/in-japans-okinawa-saving-local-languages-is-about-more-than-words/2014/11/26/f1b8e2d0-7023-11e4-a2c2-478179fd0489_story.html?utm_term=.be91e3558780

Hanihara, K. (1991). Dual Structure Model for the Population History of the Japanese. Japan Review, 2, 1-33. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790895?seq=1.

Heinrich, P. (2004). Language Planning and Language Ideology in the Ryūkyu Islands. Language Policy, 3(2), 157-165. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226350661_Language_Planning_and_Language_Ideology_in_the_Ryukyu_Islands.

Heinrich, P. (2005). Language Loss and Revitalization in the Ryukyu Islands. Asia Pacific Journal, 3(11). Retrieved from https://apjjf.org/-Patrick-Heinrich/1596/article.html.

Heinrich, P. (2014, August 25). Use Them or Lose Them: There’s More at Stake than Language in Reviving Ryukyuan Tongues. The Japan Times. Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2014/08/25/voices/use-lose-theres-stake-language-reviving-ryukyuan-tongues/#.W-WTny2ZNAY.

Heinrich, P., Ishihara, M. (2017). Ryukyuan Languages in Japan. In C. A. Seals, S. Shah (Eds.), Heritage Language Policies Around the World (pp.165-184). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319057559_Ryukyuan_Languages_in_Japan

Heinrich, P., Miyara, S., & Shimoji, M. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614511151.

Hudson, M. (1999). Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

In the News: Genetic Differences Found Between Mainland and Okinawan Japanese. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/yayoi-era-yields-up-rice/who-were-the-yayoi-people/in-the-news-genetic-differences-found-between-mainland-and-okinawan-japanese/.

Japanese Language. (2020, August 25). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_language#Prehistory.

Japonic Languages. (2020, September 30). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japonic_languages.

Jiadong, Y. (2013). Satsuma’s Invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom and Changes in the Geopolitical Structure of East Asia. Social Sciences in China, 34(4), 118- 138. doi: 10.1080/02529203.2013.849088.

Lee, S. and Hasegawa, T. (2011). Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis Supports an Agricultural Origin of Japonic Languages. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278, 3662-3669. http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.0518.

Lees, R. B. (1956). Shiro Hattori on Glottochronology and Proto‐Japanese. American Anthropologist, 58: 176-177. doi:10.1525/aa.1956.58.1.02a00160

Lexical Similarity. (2020, August 14). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexical_similarity.

Minority Rights Group International. (2018, April). World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Japan: Ryukyuans (Okinawans). Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/49749cfdc.html.

Mitchell, J. (2015, March 30). The Battle of Okinawa: America’s good war gone bad. Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2015/03/30/issues/battle-okinawa-americas-good-war-gone-bad/.

Miyara, S. (2018, June 25). Okinawan Language. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Ed. Retrieved from http://oxfordre.com/linguistics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-301.

Moseley, Christopher (ed.). (2010). UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php?hl=en&page=atlasmap.

Okinawan Language. (2020, September 15). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okinawan_language.

Okinawan Scripts. (2020, January 31). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okinawan_scripts.

Okinawans. (n.d.). In Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/history/ancient-history-middle-east-biographies/ryukyuans.

Pellard, Thomas (2011). The historical position of the Ryukyuan Languages. Historical linguistics in the Asia-Pacific region and the position of Japanese. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, Japan, 55–64.

Ryukyu Independence Movement. (2020, September 20). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyu_independence_movement.

Ryukyuan Languages. (2020, September 15). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages.

Sakihara, M. (2009). History and Okinawans. Mānoa, 21(1), 134-139. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475063.

Serafim, Leon. (2003). When and from where did the Japonic language enter the Ryukyus?

In Nihongo keitōron no genzai (Perspectives on the origins if the Japanese language), ed.

by Alexander Vovin and Toshiki Osada, Kyoto: Kokusai Nihon Bunka Sentā.

Serita, K. (2015). The Senkaku Islands. The Japan Institute of International Affairs. Retrieved from http://www2.jiia.or.jp/en/digital_library/rule_of_law.php.

Shimoji, Michinori; Pellard, Thomas, eds. (2010). An Introduction to Ryukyuan languages. Tokyo: ILCAA.

Shunten. (2020, August 21). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shunten.

Takara, Ben (2007). “On Reclaiming a Ryukyuan Culture.” Connect. Irifune: IMADR. 10(4): 14–16.

Tinello, M. (2018). A New Interpretation of the Bakufu’s Refusal to Open the Ryukyus to Commodore Perry. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16(17). Retrieved from https://apjjf.org/-MarcoTinello/5196/article.pdf.

Tipton, E. K. (1997). Society and the State in Interwar Japan. London, U.K.: Routledge.

Tomita, T. (2015, June 23). American-Okinawan Working to Keep Ryukyu Language Alive. The Japan Times. Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/06/23/national/american-okinawan-working-keep-ryukyu-language-alive/#.XE_C39hKjs0.

Twine, N. (1988). Standardizing Written Japanese. A Factor in Modernization. Monumenta Nipponica, 43(4), 449-456. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2384796?seq=24#metadata_info_tab_contents.

“UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger.” Unesco.org.

Useful Okinawan Phrases (2020). In Omniglot: The Online Encyclopedia of Writing Systems and Languages. Retrieved from https://www.omniglot.com/language/phrases/okinawan.php.

Yamaguchi-Kabata, et al. (2008). Japanese Population Structure, Based on SNP Genotypes from 7003 Individuals Compared to Other Ethnic Groups: Effects on Population-Based Association Studies. AJHJ, 83(4), 445-456. Retrieved from

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929708004874#bib33.

Yayoi Culture. (2013, July 30). In New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Yayoi_culture&oldid=971713.

Yonamine, M. (Winter 2016-2017). Uchinaaguchi: The Language of My Heart. Rethinking Schools, 31(2). Retrieved from http://rethinkingschools.aidcvt.com/archive/31_02/31-2_yonamine.shtml.

Image Credits

Bob Moore, President Nixon and Prime Minister Eisaku Sato of Japan at San Clemente, 01/05/1972, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sato_and_Nixon_1972.png

Dialect Tag (Hogen Huda), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialect_card#/media/File:Esempio_di_hogen_fuda.jpg, public domain

Charles Eugene Gail, “Portrait of little girl with baby brother on back,” The Gail Project, accessed June 28, 2021, https://gailproject.ucsc.edu/items/show/160.

Child Soldier in Okinawa, 米国連邦政府, 15 August 2015, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Childsoldier_In_Okinawa.jpg

Enirac Sum, translated by Zakuragi, Map of Japanese Dialects, 22 July 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_dialects-en.png

King Sho-Tai of the Ryukyuan Kingdom, https://en.wi

King Shō Nei, 1564-1620, 1796, Shō Genko, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Sho_Nei.jpg

Logo of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:United_States_Civil_Administration_of_the_Ryukyu_Islands_Logo.JPG, public domain

Map of the Ryukyuan Islands, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_languages#/media/File:Ryukyuan_languages_map.png, public domain

Moé Yonamine, https://www.zinnedproject.org/author-bios/moe-yonamine/

Mouagip, Flag of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 14 August 2010, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_UNESCO.svg.

Okinawa Educational School, 10 January 1946, US Military Photograph, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Okinawa_Educational_School.JPG.

The Ryūkyūan languages map: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ryukyuan_languages_map.png

UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/in/rest/annotationSVC/Attachment/attach_cmsUpload_69ed8530-5661-459d-b0ef-7f29e2cb8fff

Credits

Posted: June 25, 2021

Previous versions: 7 Oct 2021

Contributing Analysts: Tyler Jackson

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina