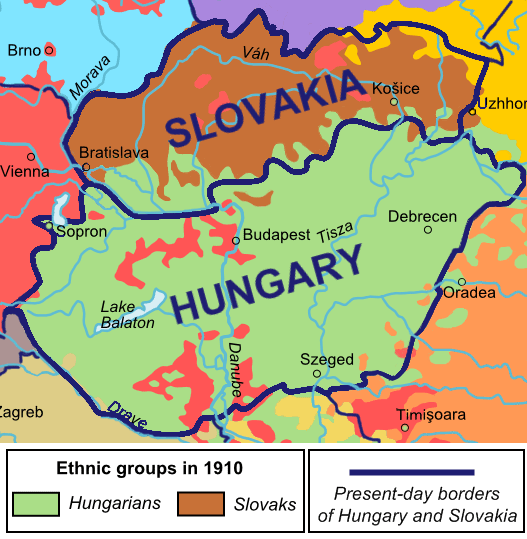

The language conflict of Hungarians in Slovakia can be described as geopolitically generated. Historically, many Slovakian tribes were oppressed under Hungarian rule. However, with the shifting of borders, the once majority population can become a minority in a short time span. The dissolution of the Austria-Hungarian empire displaced many Hungarians in Slovakia. The Treaty of Trianon of 1920, which formally ended World War I, redrew the borders of the former empire and created a new state, Hungary. Many ethnically Hungarian peoples were left outside of the newly declared nation. Previously, many Slovaks in Hungary were mistreated and had little language rights, and the shifting balance of power allowed some Slovaks to act on their prejudice against Hungarians. This conflict still causes tension between Slovaks and Hungarians, especially with language laws passed as recently as 2009 that mandate the use of Slovak in public life.

Historical Background

Relations between Hungarians and Slovaks span over 1,100 years, many of them marked by conflict [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. Slavic tribes came to live in the lands surrounding the Danube during the 5th century CE, where they fell under the leadership of Samo. The Principality of Moravia emerged around what is present-day Slovakia by the end of the 8th century. Soon after, the Principality of Nitra was established to the south by other Slavic tribes. The two principalities were merged into Great Moravia in 833 when Prince Mojmir I of Moravia conquered Nitra. Great Moravia was then conquered in the early 900’s by the Magyars, or Hungarians [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017].

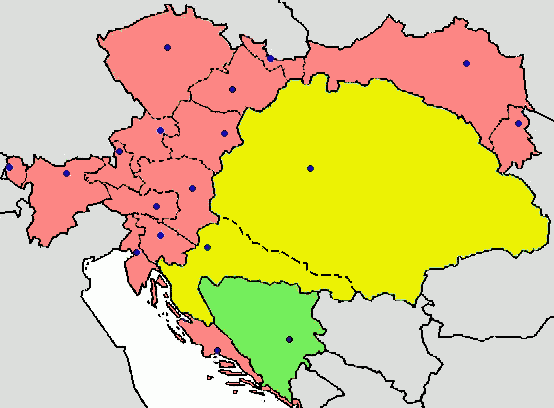

Although the exact origin of the Magyars is unknown, many scholars agree that they migrated from Eurasian grasslands to the far north-east. It is believed that their tribes arrived near the Carpathian Basin (present-day Slovakia and Hungary) by the early 10th century [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. Magyar rule would continue until well into the 20th century. The territory came under Hapsburg rule in 1526, breaking into Habsburg Hungary and Ottoman Hungary. The Habsburgs regained control of Hungary in 1686, where they would reign until 1867. Latin was the official language of the kingdom [New World Encyclopedia, 2018]. Following a failed Hungarian revolution in 1848 and the weakening of the empire, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 declared a dual-monarchy wherein the Austrian Empire was divided between the two (newly formed) countries. As part of this Compromise, the newly sovereign Kingdom of Hungary acquired present-day Slovakia, and the Slovaks would be under rule of the Magyars until the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 [Bradley, Hauner, Odlozilik, Wiskemann, & Zeman, 2016].

Originally, the Hungarians respected the language rights of the Slovak minority. With explicit protection such as the 1868 Nationality Act and the Education Act, equal rights allowed minority groups to retain language rights. However, in the drive to form a cohesive and nationalized Hungary, these laws soon became obsolete and overruled. New policies targeted education in order to assimilate Hungarian as the only official language, in a process known as Magyarization; policies such as the 1879 and 1883 Education Acts not only required teachers to speak in Hungarian in the classroom (in addition to teaching the language), but also restricted the use of minority languages [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. The Magyarization of education was detrimental to ethnic minorities; not only did they receive substandard education in the Hungarian language, but they were also alienated. Furthermore, minority citizens were pressured to either misspell their names in order to conform to Magyar spelling or convert their non-Magyar names to a Hungarian equivalent, even in predominantly minority communities. However, this treatment would be reversed after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of WWI.

Hungarian Dual-Citizenship Law

In May, 2010, the Hungarian government almost unanimously passed a law declaring that any ethnically Hungarian peoples living outside of Hungry would be able to file for dual-citizenship [Than & Santa, 2010]. Thousands of ethnic Hungarians in surrounding countries, such as Romania, flooded Hungarian consulates in order to apply for citizenship when the law went into effect in January of 2011 [Peter, 2011). Many of the countries that would be affected by Hungarian dual-citizenship were already members of the EU, meaning that citizens from those countries could already travel and work within Hungary, making their decision a symbolic one [Peter, 2011]. This law is also a rebuttal to Slovakia’s 2009 language law, which condemns minority language rights. Slovakia was the only surrounding nation to object the legislation, calling it a “security threat” and an attempt to return to Hungary’s original borders [BBC, 2012].

In retaliation, Slovakia released a 2010 amendment to its own citizenship law. This amendment, designed to strip Slovakian citizenship from anyone that applies for citizenship in another nation, halted many ethnically Hungarian citizens from applying [Than & Santa, 2010]. In addition to losing Slovakian citizenship, those who chose to move ahead would be denied the right to vote in either the country: the 2010 amendment made it so non-citizens could not vote in Slovak elections [The Slovak Spectator, 2012], and only Hungarian residents qualify to vote there [Peter, 2011]. This ensures that the Hungarian minority is systematically and legally silenced and stripped of the right to vote in their interest. They are instead forced to choose between moving to Hungary and declaring full citizenship or staying in their homes under the oppressive Slovakian legislation.

Language Law

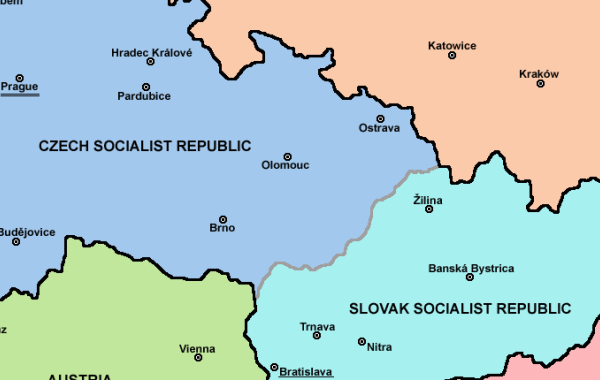

Even prior to the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, laws restricted the use of minority languages. The 1990 Act on the Official Language of the Slovak Republic declared Slovak as the singular official language of the Slovak Republic, albeit while still allowing Czech on official documents [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. The Act stipulated that all official records and documents of the government had to be written in Slovak, purging the use of minority languages from government business. Those minority languages were only allowed to be spoken publicly in places where minority citizens made up at least twenty percent of the population. The 1992 Slovak Constitution continued the restrictions placed on minority language rights in 1990, albeit with language designed to appease EU critiques. Minority language speakers were afforded rights, such as the right to education in their native language, but such rights were heavily regulated by the authorities [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017].

In 1995, the Slovak State Language Law made the prior Slovak-only language ideals more concrete. The use of a minority language, regardless of whether it was in a population of at least twenty percent minority citizens, became punishable through fines, and all official documents, education, commerce, and public meetings would only be conducted in Slovak [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. The law extensively outlined when the use of other languages would be acceptable. Public signs, for example, could only include another language if Slovak was at least the same size and preceded the other script. Not only did this law strain relations with Hungary – as Hungarian was the primary language being restricted - but it also incited outcry from other European countries and organizations. Demands for clear minority language rights were ignored, as were demands from the National Council to reverse the law. European disapproval of this infringement led to the rejection of Slovakia’s initial application to join the European Union. In 1999, a law defining minority rights seemed to reverse many of the provisions of the 1995 law, including the fines imposed as punishment for using a minority language. However, this law still left many legal intricacies to the discretion of authorities and did little to outline rights dealing with education, media, or public promotion [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017].

In 2009, the 1995 law was revitalized. Minority schools would once again be required to conduct business in Slovak, and even gravestones would have to be recurved unless they were originally written in Slovak [Schöpflin, 2009]. In addition, fines of up to 5000 euros would be enforced for the use of “incorrect” Slovak or a minority language in public. This was, once again, met with public outcry from across the globe, with many countries and organizations criticizing the Slovakian government for such a restrictive law [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. While all linguistic minorities were restricted by the law, as Hungarians comprised ~10% of Slovakia’s population, they felt particularly targeted. This, combined with the Czech population being exempt from the law despite also being a minority served to further damage relations between Slovakia and Hungary [Schöpflin, 2009], leading to Hungarian protests against the law [BBC, 2009].

The 2009 law fueled a Hungarian campaign to create a national identity to include those living in surrounding countries. In 2010, Hungary passed a dual-citizenship law, declaring that any ethnic Hungarians that spoke Hungarian and could prove their ancestry would be eligible to apply for dual-citizenship. Slovakia was the only neighboring country to reject the move [BBC, 2012].

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

- Genealogy/Relatedness

The linguistic backgrounds of Hungarian and Slovak are as different as their historical backgrounds. Hungarian (magyar nyelv) belongs the Ugric subfamily of the larger Finno-Ugric language family. Well known languages of this group include Finnish, Estonian, and Saami. Lesser known, but more closely related languages include Mansi and Khanty, found near the Ural Mountains in northwestern Siberia, Russia [Michalove, 2002].

Slovak (slovenčina, slovenský jazyk) is a Slavic language, closely resembling other Slavic languages such as Russian, Bulgarian, and most closely, Czech and Polish. The Czech-Slovak group developed within West Slavic during the high medieval period, and the standardization of Czech and Slovak within the Czech-Slovak dialect continuum emerged in the early modern period [Short, 2002].

2. Phonetics/Phonology

Hungarian vowel inventory includes 14 vowel phonemes (i.e., seven pairs of short and long vowels). Most of the vowel pairs vary significantly in their duration, but pairs a/á and e/é also differ in closedness and length. Hungarian includes 25 consonant phonemes. Consonant length is a distinctive in Hungarian, as most consonants can occur as geminates [Siptár & Törkenczy, 2007; Szende, 1994].

Slovak includes 10 vowels (i.e., five pairs of short and long vowels). This durational distinction is similar to Hungarian. Slovak includes 29 consonants [Hanulíková & Hamann, 2010].

- Morphology and Grammar

Hungarian has rich inflection of nouns and verbs. Inflections on nouns mark number (singular and plural) and case (at least 17, although the exact number is disputed), while verbs are marked for number, person, tense, and mood. Furthermore, indicators for case, gender, and number are formed by adding affixes, making it an agglutinating language. Conjugated verbs consisted of a stem, followed by two suffixes, one to indicate tense or mood (present/past and conditional/subjunctive) and another to indicate person and number [Davies & Dubinsky, 2018]. Hungarian uses vowel harmony to attach suffixes to words, that is, most suffixes have two or three different forms, depending on the vowels of the head word. Hungarian also utilizes markers to indicate definiteness, definite and indefinite, which are similar to English. The neutral word order is subject-verb-object (SVO). However, Hungarian is a topic-prominent language, and its word order may depend on the topic-comment structure of the sentence (e.g., what aspect is assumed to be known and what is emphasized) [Keresztes, 1999; Rounds, 2001].

Slovak nouns inflect for number and six cases. Unlike Hungarian, Slovak nouns have gender (feminine, masculine, neuter) and do not use affixes, but morphemes instead. This means that indications of case, gender, and number are fused into a single word. Moreover, the verbs inflect for person, number, and tense (past, present, future) [Davies & Dubinsky, 2018]. Word order in Slovak is relatively free due to inflection allowing for the identification of grammatical roles (i.e., subject, object, predicate) regardless of word placement. Somewhat similarly to Hungarian this relatively free word order allows to convey topic and emphasis [Mistrík, 1988].

4. Lexicon and Vocabulary

The basic vocabulary of Hungarian (numbers, body parts, most frequent verbs, etc.) shares several hundred word roots with other Uralic languages like Finnish, Estonian, Mansi and Khanty. The language also came into contact with a variety of speech communities, among them Slavic, Turkic, and German. Many agriculture and livestock lexical items are of Chuvash (one of Turkic languages) origin [Marcantonio et al., 2001; Sala, 1988; Schulte, 2009].

The highest number of borrowings in the Slovak vocabulary come from Latin, German, Czech, Hungarian, Polish and Greek. Recently, it is also influenced by English [Kopecká et al, 2011].

- Orthography/Writing System

Hungarian writing originated in a form of right-to-left Old Hungarian runes. After the Kingdom of Hungary was established in the year 1000, the Latin alphabet gradually replaces the runes. Contemporary Hungarian is written in Latin alphabet with additional modified letter-symbols, which include vowels with acute accents (á, é, í, ó, ú) to represent long vowels, and umlauts (ö and ü) and their long counterparts ő and ű to represent front vowels. Additionally, there are eight letters made up of two characters (cs, dz, gy, ly, ny, sz, ty, zs), and one letter made up of three characters (dzs). In Hungarian these combinations of characters are considered separate letters [Korompay, 2012].

Slovak uses the Latin script with modifications that include the four diacritics (ˇ, ´, ¨, ˆ) placed above certain letters (a-á,ä; c-č; d-ď; dz-dž; e-é; i-í; l-ľ,ĺ; n-ň; o-ó,ô; r-ŕ; s-š; t-ť; u-ú; y-ý; z-ž). Due to the diacritics, Slovak alphabet has 46 letters (Omniglot).

- Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

Until 1920 Slovakia was part of the Hungarian Kingdom. In the late 19th century, school instruction was switched to Hungarian in the Slovak region. When Czechoslovakia was established after World War I, Slovakia became a part of that newly established state. After World War II, when Slovakia was still part of Czechoslovakia, the public use of Hungarian was forbidden, and Hungarian schools were closed. During the communist time (1948-1989), Hungarian was allowed again, and the Hungarian schools were re-opened.

The Hungarian language is seen by some as a threat in present Slovakia, especially for those Slovaks living in areas where Hungarian is the majority language. At the same time, the Hungarians refrain from speaking Hungarian in order to avoid conflicts with Slovaks. Therefore, even though the Hungarians represent the majority in the southern area of Slovakia, the Hungarian language is not used as extensively [Laihonen, 2016].

In 2009 the Slovak parliament mandated the use of the Slovak language in all government and state institutions. The amendment stated that the use of any other language than Slovak could carry a fine, although the minority languages could still be used in private matters. This policy led the Hungarian government to accuse Slovakia of discriminating Hungarian speakers [Groszkowski & Bocian, 2009].

Resources

BBC. (2009, September 2). Protests over Slovak language law. Retrieved October, 2018, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8232878.stm

BBC. (2012, March 12). Slovaks retaliate over Hungarian citizenship law. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/news/10166610

Bradley, J., Hauner, M., Odlozilik, O., Wiskemann, E., and Zeman, Z. (2016, March 6). Czechoslovak History. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Czechoslovak-history.

CIA (2021, July 7). The World Factbook: Slovakia. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/slovakia/.

Davies, W, and Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge UP.

Department of Slavic, Eastern European, & Eurasian Languages & Cultures. (2021). Background Information. Retrieved October, 2018 from https://slavic.ucla.edu/languages/hungarian/background-info/

Davies, W., & Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights: Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge UP.

European Commision. (2016, December 6). Accession criteria. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/policy/glossary/terms/accession-criteria_en

Groszkowski, J., Bocian, M. (2009). The Slovak-Hungarian dispute over Slovakia’s language law. Center for Eastern Studies, 30, 1-5.

Hanulíková, A., & Hamann, S. (2010). Slovak. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40(3): 373–378.

Keresztes, L. (1999). A Practical Hungarian Grammar (3rd ed.). Debrecen: Debreceni Nyári Egyetem.

Kopecká, M., Laliková, T., Ondrejková, R., Skladaná, J., Valentová, I. (2011). Staršia slovenská lexika v medzijazykových vzťahoch. Bratislava: Jazykovedný ústav Ľudovíta Štúra SAV, 10–46.

Korompay, K. (2012). 16th-century Hungarian orthography. In Orthographies in Early Modern Europe, 321-349.

Laihonen, P.(2016). Hungarian language in Slovakia. Retrieved 14 July 2021 from https://blogs.helsinki.fi/ceren-eri/hungarian-language-in-slovakia/.

Marcantonio, A., Nummenaho, P., & Salvagni, M. (2001). The "Ugric-Turkic Battle: A Critical Review. Linguistica Uralica, 2.

Michalove, P. A. (2002). The Classification of the Uralic Languages: Lexical Evidence from Finno-Ugric. Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, 57.

Mistrík, J. (1988). A Grammar of Contemporary Slovak (2nd ed.). Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo.

Rounds, C. (2001). Hungarian: An essential grammar. London; New York: Routledge.

Sala, M. (1988). Vocabularul reprezentativ al limbilor romanice [Representative vocabulary of the Romance languages]. Bucharest: Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică.

Schulte, K. (2009). Loanwords in Romanian. In Haspelmath, Martin; Tadmor, Uri (eds.). Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Siptár, P., & Törkenczy, M. (2007). The Phonology of Hungarian. In The Phonology of the World’s Languages. Oxford University Press.

Szende, T. (1994). Illustrations of the IPA: Hungarian. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 24(2): 91–94.

Short, D. (2002). Slovak. In Comrie, B. & Corbett, G. G. (eds.), The Slavonic Languages, London and New York: Routledge

Schöpflin, G. (2009, July 10). The Slovak language law is discriminatory and restrictive. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://euobserver.com/opinion/28440

Than, K. & Santa, M. (2010, May 25). Hungary citizenship law triggers row with Slovakia. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-citizenship-slovakia/hungary-citizenship-law-triggers-row-with-slovakia-idUSTRE64O32220100525

Peter, L. (2011, January 4). New Hungary citizenship law fuels passport demand. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-12114289

The Slovak Spectator. (2012, March 10). ELECTION 2012: Some Slovak voters prevented from voting by officials. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://spectator.sme.sk/c/20042732/election-2012-some-slovak-voters-prevented-from-voting-by-officials.html

New World Encyclopedia. (2018, April 18). Kingdom of Hungary. Retrieved October, 2018, from http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Kingdom_of_Hungary

Editors of the Encyclopedia Britannica. (2018, May 28). Treaty of Trianon. Retrieved October, 2018, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Trianon

Slovak Republic. (2015). Joining the EU. Retrieved October, 2018, from http://www.slovak-republic.org/eu/

Slovak. Omniglot. Retrieved 12 July 2021 from https://omniglot.com/writing/slovak.htm.

Image Credits

Cisleithanien Transleithanien [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons; creator attribute: Kpalion / modified by AndreasPraefcke ]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cisleithanien_Transleithanien.png

Czechoslovakia [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Czechoslovakia.png

EU-Slovakia [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons; creator attribute: NuclearVacuum]. (2009, October). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8105290

Fico Juncker (cropped) [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons; creator attribute: EU2016SK]. (2016, June 30). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50674152

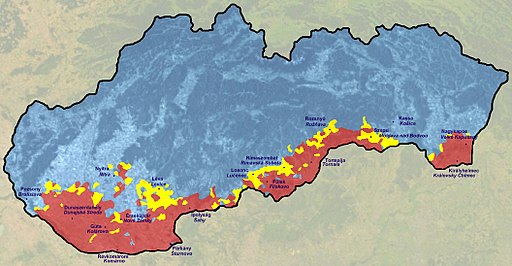

Hungarians in Slovakia 2 [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons; creator attribute: Qorilla]. (2009, September 2). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hungarians_in_Slovakia_2.jpg

Hu-sk-1910enthnographics-with-current-borders [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons; creator attribute: Qorilla]. (2009). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hu-sk-1910enthnographics-with-current-borders.png

Kőszeg trianon [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2006, July). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:K%C5%91szeg_trianon.jpg

Credits

Uploaded: August 2021

Previous Versions: Feb 2021

Contributing Analysts: Grace Alger

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina