South Africa has been home to a variety of languages since the fourth century C.E., when various Bantu groups migrated to the region and encountered the native Khoisan people. Centuries later, the Dutch and the English imperial powers added further conflict as they prioritized their own respective tongues over Bantu languages. The imperial countries also experienced conflict between themselves. The British drove speakers of Afrikaans (a derivative of Dutch) inland, but they could not eradicate the language, and the British-Boer wars eventually led to the formation of the state of South Africa in 1900. Forty years later, the National Party came to power and segregated black Africans partly due to their languages in an attempt to re-tribalize the country in the apartheid system. This lasted until 1996, when a new constitution changed the nation from bilingual (Afrikaans and English) to a multilingual state with eleven official languages, finally recognizing indigenous Bantu languages. The country still struggles to find a political and cultural balance with so many languages and their charged history, particularly in the education system.

Historical Background

Roughly 2,000 years ago, genetically similar groups of aboriginal people known variously as the San, Khoi, Khoikhoi, Khoisan, Hottentots, or Bushmen lived in the geographic region modernly recognized as South Africa. Around 300 C.E., Bantu-speaking groups arrived in the eastern parts of South Africa. Initial relations included trade and intermarriage; however, the Bantu eventually dominated the area after seizing increasingly large tracts of farmland via technologically superior processes and immunity to disease. By 500 C.E., the Bantu were formally established in the central, inland portions of the region, and continued to expand through a succession of kingdoms during the 9th through 16th centuries.

Near the end of the 17th century, the Dutch established the first permanent settlement in Cape Town. For 100 years, the Dutch were the only significant linguistic and cultural European presence. The ruling Dutch East India Company (VOC) required other European migrants to the Cape, like the French Huguenots, to adopt the Dutch language. Settlers, who called themselves “Boers,” spoke a derivative of Standard Dutch called Afrikaans and moved inland to escape the oppressive rule of the VOC.

In 1775, the British seized the Cape Colony and finalized ownership at the 1815 Congress of Vienna. The British outlawed the use of Dutch language in favor of promoting the British language and culture. In response, the Dutch moved further inland.

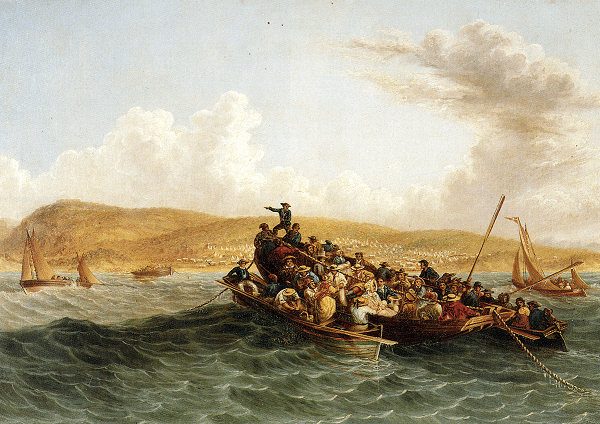

In 1820, the United Kingdom persuaded several thousand British citizens to settle in areas around Port Elizabeth. Just two years prior, King Shaka Zulu had seized tribal territory in eastern South Africa and centralized it as an ethnically-Zulu state, driving Bantu groups from the territory. In 1832, the British Empire abolished slavery but continued to enforce the use of English language, which drove Afrikaans-speaking Boers deeper inland into regions not controlled by the British Empire (i.e. Natal, Transvaal, and the Orange Free State). These migrations resulted in conflicts among native tribal groups, Bantu tribes expelled by Zulu occupation, and the Boers fleeing the British Empire.

The Anglo-Boer Wars of 1880 and 1899 were inspired by British desire to consolidate imperial control over South Africa and the Boer’s desire to preserve their independence. In 1909, the British empire formed the Union of South out of the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, and the Orange Free State.

Following its rise to power in 1948, the National Party began to support African languages in an attempt to “retribalize” Africans into separate ethnic groups. By promoting the use of African languages, the government justified relocating individuals to place them into regions where their native tongue was a majority. This divide-and-rule policy effectively partitioned the country into areas of ethnic homogeneity called “homelands” that advanced the racially discriminatory ideals of apartheid.

In 1994, apartheid fell, and the country began to institute democratic reforms, including the constitution of 1996 that, for the first time, addressed the issues of official national languages.

Soweto Youth Uprising

In 1976, the South African government passed the Afrikaans Medium Decree, which required that schools be taught equally in English and Afrikaans, with some subjects to be taught exclusively in Afrikaans. Many students, primarily black, who did not speak Afrikaans were now unable to understand their classes. Additionally, black Africans saw Afrikaans as the language of the oppressor, derived from the Dutch who were the first Europeans to colonize South Africa.

This event was the catalyst that sparked outrage stemming from decades of oppression in South African schools, beginning in 1953 with the Bantu Education Act. This act wrested control from regional authorities and put Bantu schools under the control of the Department of Native Affairs. After the Afrikaans Medium Decree, students in Soweto began protests which came to a climax on June 12, 1976.

On June 12, somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 students arranged a secret protest, walking out of school to a nearby stadium. The peaceful crowd was holding signs and singing when the police arrived with teargas. Those gathered dissolved into chaos as the police began firing live rounds into the crowd of students. The death toll for that day is disputed: the official police report was 23, while a government inquiry counted 575 deaths caused by the police.

One picture from the tragedy became widely used as evidence against the atrocities of the police. It depicts an 18-year-old boy, Mbuyisa Makhubo, carrying the blood-stained body of 12-year-old Hector Pieterson, one of the first casualties, while Hector’s sister, Antoinette Sithole, runs in anguish alongside. Sam Nzina, the photographer, was forced to flee after the government told police to kill him if they saw him taking more pictures of protests. He was eventually caught and placed under house arrest. This picture gave faces to the tragedy, and it was featured in protests that kept growing until the end of apartheid in 1994. June 12 eventually became a public holiday, National Youth Day, and the Hector Pieterson Memorial museum opened in 2002 to preserve the memory of the Soweto Protest.

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

Nine of the eleven official languages of South Africa are indigenous languages. These trace their origins to the Bantu people, who arrived in the area around 300 C.E. and gradually became more dominant as they displaced and intermarried with the native Khoisan until the arrival of Europeans beginning in the late 15th century. The nine official Bantu languages in South Africa are part of a southern group within the Bantu language family. These can be divided into two subgroups: Nguni [(isi)Zulu, (isi)Xhosa, (si)Swazi, and (isi)Ndebele] and Sotho-Tswana [Northern Sotho (Sesotho sa Leboa), (Se)Tswana, and Sesotho]. Within the subgroups, the languages are mostly mutually intelligible and could be considered dialects rather than separate languages. The other two official Bantu languages are Tsonga and (Tshi)Venda, which belong to different subgroups, Shangaan-Tsonga and Venda respectively. Although the speakers of these languages in total amount to 75% of the population, the influence of the Europeans meant that the government never recognized indigenous languages as official until 1996. The map below shows the geographic prevalence of each language.

The Dutch were the first Europeans to establish a significant presence in South Africa at the end of the 17th century, which they maintained for over 100 years. The Dutch East India Company required all other European settlers to also adopt the Dutch language, and intermarriage with the local population led to a version of Dutch that came to be known as Afrikaans-Hollands, or Afrikaans. This language shares most of its vocabulary with Dutch; the differences lie in grammar changes and spelling that reflects a different pronunciation, a reflection of the mixing of cultures in South Africa. Meanwhile, the British began to take control in the 18th century, solidifying their hold in 1815. English and Dutch both became official languages, and they remained the languages of power. Both are members of the Western group of the Germanic language family and therefore share similar characteristics. Today, Afrikaans and English are the third and fourth most spoken languages in South Africa.

Resources

Anglo-Boer War Museum, War Museum of the Boer Republics,

www.wmbr.org.za/view.asppg=research&pgsub=intro1&pgsub1=9&head1=Introduction to the War.

“Archibald Campbell Jordan.” South African History Online, 19 Mar. 2018, www.sahistory.org.za/people/archibald-campbell-jordan.

Baker, A. (2016, June 15). This photo galvanized the world against apartheid. Here’s the story behind it. Time. Retrieved

from http://time.com/4365138/soweto-anniversary-photograph/

“Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.” South African History Online, 21 Nov. 2016,

www.sahistory.org.za/article/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996.

Davies, W.D., & Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language conflict and language rights: Ethnolinguisitc perspectives on human conflict. Cambridge, U.K.:

Cambridge University Press.

“Department of Higher Education and Training Green Paper for Post-School Education and Training, 2012.” Council on Higher Education,

Department of Higher Education and Training, Apr. 2012, http://www.che.ac.za/media_and_publications/draft-legislation/dhet-green-

paper-post-school-education-and-training

“The Development of Indigenous African Languages as Mediums of Instruction in Higher Education, 2003.” Department of Higher Education and

Training, Sep. 2003,

http://www.dhet.gov.za/Management%20Support/The%20development%20of%20Indigenous%20African%20Languages%20as%20medium

s%20of%20instruction%20in%20Higher%20Education.pdf

“Dr. Neville Edward Alexander.” South African History Online, 30 Aug. 2018, www.sahistory.org.za/people/dr-neville-edward-alexander.

“Events of 1901, The South African War.” Britain in the World, The National

Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/census/events/britain5.htm.

“French Revolutionary Wars: 1791 - 1802 - Oxford Reference.” Dominant Social Paradigm - Oxford Reference, Oxford University Press, 24 Sept.

2013, www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191737817.timeline.0001.

Gaffey, C. (2016, June 16). South Africa: What you need to know about the Soweto uprising 40 years later. Newsweek. Retrieved from

https://www.newsweek.com/soweto-uprising-hector-pieterson-memorial-471090

“The June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising.” South African History Online, 6 June 2018, www.sahistory.org.za/topic/june-16-soweto-youth-uprising.

“Language Policy for Higher Education, 2002.” Department of Higher Education and Training, Nov. 2002,

http://www.dhet.gov.za/Management%20Support/Language%20Policy%20for%20Higher%20Education.pdf

“National Party (NP).” South African History Online, 10 Aug. 2017, www.sahistory.org.za/topic/national-party-np.

The South African Constiution, Department of Justice, www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/.

Credits

The Anglo-Boer War Memorial [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2012, November 10). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Anglo-Boer_War_Memorial.jpg

British Settlers Arrive in South Africa [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2016, December 1). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Britse-setlaars.png

The Constiution of the Republic of South Africa [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2014, January 19). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Constitution_of_the_Republic_of_South_Africa,_1996._023.JPG

Flag of the South African National Party [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (1935, December 1). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:National_Party_(South_Africa)#/media/File:Flag_of_the_South_African_National_Party_(1936%E2%80%931993).svg

The Fountain at the Hector Pieterson Museum [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2008, January). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_fountain_at_the_Hector_Pieterson_Museum.JPG

The Hector Pieterson Memorial [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2010, May 16). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Hector_Pieterson_Memorial_(4611836835).jpg

Jan van Riebeeck Lands in South Africa [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Bell_-_Jan_van_Riebeeck_se_aankoms_aan_die_Kaap.jpg

Khoi Breaking Down Huts [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. Retrieved from

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/Sameul_Daniell_-_Kora-Khokhoi_preparing_to_move_-_1805.jpg

Magcaba, Bongisipho. “Teachers Feel Excluded from South Africa's Schools by Race and Culture.” SABC News, SABC News, 24 Apr. 2018,

www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/teachers-feel-excluded-south-africas-schools-race-culture/.

South Africa 2011 Dominant Language Map [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2011). Retrieved from

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5c/South_Africa_2011_dominant_language_map.svg

University of Cape Town Chancellor Oppenheimer Library [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2017, August 1). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Hub,_Chancellor_Oppenheimer_Library,_University_of_Cape_Town.jpg

The University of South Africa [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (2013, July 12). Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_University_of_South_Africa.jpg

Zulu attack Boers [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Bell_-

_Zoeloe-aanval_op_%27n_Boerelaer_-_1838.jpg