Language Law

Even prior to the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, laws restricted the use of minority languages. The 1990 Act on the Official Language of the Slovak Republic declared Slovak as the singular official language of the Slovak Republic, albeit while still allowing Czech on official documents [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. The Act stipulated that all official records and documents of the government had to be written in Slovak, purging the use of minority languages from government business. Those minority languages were only allowed to be spoken publicly in places where minority citizens made up at least twenty percent of the population. The 1992 Slovak Constitution continued the restrictions placed on minority language rights in 1990, albeit with language designed to appease EU critiques. Minority language speakers were afforded rights, such as the right to education in their native language, but such rights were heavily regulated by the authorities [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017].

In 1995, the Slovak State Language Law made the prior Slovak-only language ideals more concrete. The use of a minority language, regardless of whether it was in a population of at least twenty percent minority citizens, became punishable through fines, and all official documents, education, commerce, and public meetings would only be conducted in Slovak [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. The law extensively outlined when the use of other languages would be acceptable. Public signs, for example, could only include another language if Slovak was at least the same size and preceded the other script. Not only did this law strain relations with Hungary – as Hungarian was the primary language being restricted - but it also incited outcry from other European countries and organizations. Demands for clear minority language rights were ignored, as were demands from the National Council to reverse the law. European disapproval of this infringement led to the rejection of Slovakia’s initial application to join the European Union. In 1999, a law defining minority rights seemed to reverse many of the provisions of the 1995 law, including the fines imposed as punishment for using a minority language. However, this law still left many legal intricacies to the discretion of authorities and did little to outline rights dealing with education, media, or public promotion [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017].

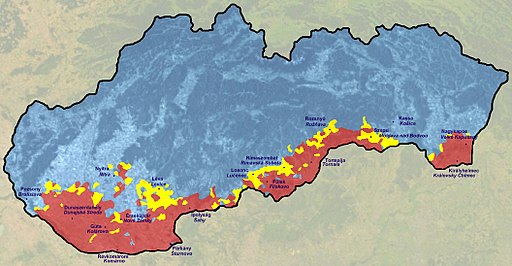

In 2009, the 1995 law was revitalized. Minority schools would once again be required to conduct business in Slovak, and even gravestones would have to be recurved unless they were originally written in Slovak [Schöpflin, 2009]. In addition, fines of up to 5000 euros would be enforced for the use of “incorrect” Slovak or a minority language in public. This was, once again, met with public outcry from across the globe, with many countries and organizations criticizing the Slovakian government for such a restrictive law [Davies and Dubinsky, 2017]. While all linguistic minorities were restricted by the law, as Hungarians comprised ~10% of Slovakia’s population, they felt particularly targeted. This, combined with the Czech population being exempt from the law despite also being a minority served to further damage relations between Slovakia and Hungary [Schöpflin, 2009], leading to Hungarian protests against the law [BBC, 2009].

The 2009 law fueled a Hungarian campaign to create a national identity to include those living in surrounding countries. In 2010, Hungary passed a dual-citizenship law, declaring that any ethnic Hungarians that spoke Hungarian and could prove their ancestry would be eligible to apply for dual-citizenship. Slovakia was the only neighboring country to reject the move [BBC, 2012].