The Galician language conflict is a centuries-long competition between a dominant (Castilian Spanish) and a non-dominant (Galician) language. Galicia went through its ‘golden age’ at the very beginnings of Spanish history, before experiencing a millennia long decline until Galician was relegated to use in the home [Beswick, 2007: 58-59; D’Emilio, 2015: 362-64, 430]. Through the 19th century Rexurdimento (‘Resurrection’) and 20th century Irmandades de Fala (‘Brotherhood of Speech’) and Xeración Nós (‘The Generation of Us’), a burgeoning culture arose around the language, including newspapers and literature that promoted usage of Galician and its preservation [Beswick, 2007: 63-65, 67-68]. The destruction during, and oppression after, the Spanish Civil War reversed decades of Galician cultural progress. This reversal, however, proved to be relatively brief, as the 1981 Statute of Autonomy of Galicia, coupled with future acts to normalize and strengthen the protections granted by the national government to the now autonomous community, finally cemented the position of this regional language after centuries of unease, oppression, and loss [Share, 1986: 557; Xunta de Galicia, 2009; D’Emilio, 2015: 915].

Today, the Galician language is diminished and endangered by the region’s dependence on the Spanish state, and a large monolingual Castilian population living in Galician cities, many of whose identity is now equal parts Spanish and Galician. Economically, Galicia’s development trails that of the Basque Country and Catalonia, two of the most prosperous regions in Spain, partly on account of its remote location and rural history, and so has struggled to keep up with these other regions in the protection and promotion of their language and culture. Although neofalantes, new speakers of Galician, have taken up the language and efforts such as Radio Galicia and inclusion of Galician in the education system have been implemented, Galicia has not seen the same magnitude of development and promotion of its language as have other autonomous language communities within the Spanish state [O’Rourke & Ramallo, 2015 pg. 148; O’Rourke, 2018; CRTVG, n.d.]. Still, Galician linguistic development has continued despite setbacks such as the difficulty they’ve had in encouraging its use among the younger generation. The language conflict in Galicia, therefore, centers on the struggle for the revival and maintenance of a language that, over the centuries, had suffered decay in a rural region with high outmigration.

Historical Background

Over the centuries, Galicia has evolved from a patchwork of kingdoms into an autonomous kingdom of Spain. Prior to the Reconquista, Galicia was not culturally Latin; it was Visigoth and Celtic, which is seen in the traditions, folklore, and history of the region [D’Emilio, 2015; Silva, 2015; Warf & Ferras, 2015: 259-260]. Galicia was founded in 409, became part of the Visigoth Kingdom in 585, and was then united under the Kingdom of Asturias (a Christianized Visigothic entity) in the 8th century [Phillips, W.D. & Phillips, C.R., 2010]. This was a prominent starting point for the Reconquista: Pelayo, who formed the Kingdom of Asturias in an effort against the Moorish invaders of Al-Andalus, originated in the Cantabrian Mountains that span through Galicia, and was, according to Phillips and Phillips, “The first leader of Christian resistance to the Muslim conquest” [2010: 56]. However, Galicia’s early prominence was undercut by the greater and later success of Portugal and the rest of Spain[Keating, 2001: 226].

Galicia and Portugal were effectively a single region prior until the end of the 11th century [Warf & Ferras, 2015: 260]. By the end of the 12th century, the histories of Galicia and Portugal had thoroughly separated, and this separation would prove permanent [D’Emilio, 2015: 362-364; Warf & Ferras, 2015: 260]. In 1230, the Kingdom of Leon became united with the Crown of Castile and, from this point, Galicia began to suffer a long cultural and regional decline [D’Emilio, 2015: 364]. This was due in part to Galicia’s distance from the more influential eastern half of Spain, the domination of the western coast by Portuguese ports, and the rise of Castile as the flourishing center of the nation [Keating, 2001: 226; Newcomb, 2017: 72-73; Screti, 2018; Consello da Cultura Galega, n.d.]. Galicia’s language and culture became associated with the countryside and everyday speech while Castilian became primary language of the region.

The Rexurdimento – a renaissance of Galician culture, literature, and language – began in 1863, and attempted to combat the decline of Galician. Throughout the latter half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, efforts were established to slow the decline of the language. The freedoms imparted by the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939) allowed Galician to become a co-official language of the region, along with Castilian, while the proliferation of groups such as the Irmandades da Fala (Brotherhood of Speech) and the Xeración Nós (“We Generation”) continued the work of the Rexurdimento by publishing Galician magazines and other literary works [Screti, 2018]. However, the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the installation of the fascist Francoist government ended this growth via official restrictions on the use of any languages other than Castilian.

Following the fall of the Francoist regime, the 1978 Spanish Constitution allowed for the creation of autonomous zones, leading to the 1981 Statute of Autonomy of Galicia. This statute once again grants Galician co-official language status and has led to a revitalization of the language and culture that continues today. While this has been a success, younger generations are increasingly choosing Castilian as their first language in hopes of finding better job prospects, leading to renewed tensions over the language's future.

Galicia: The Seventh Celtic Nation?

Galicia’s cultural heritage has a complex relationship to its linguistic heritage. Although Galician is a Romance language closely related to Latin, the language, as well as its culture, retains elements of Celtic mythos and linguistics [Herbert, 2014]. The name Galicia itself comes from the Gallaeci, a Roman-era Celtic tribe that inhabited northwestern Spain. However, as Celtic historian Peter Beresford Ellis states in an interview with Transceltic in 2013: “Celtic is a linguistic term; a Celt is one who speaks or was known to have spoken within modern historical times a Celtic language. That is central.” [McIntyre, 2013]. Because extant languages were significant criteria for entry, Galicia was denied entry to the Celtic Nations, despite both a revival of recognition of Celtic identity in the post-Franco period and an interest in the region’s Celtic roots [Mcintrye, 2013]. However, there is increased recognition that Galicia is a seventh Celtic nation, and that many of their traditions—bagpipes in traditional music; druids, spirits, and witches in folklore; and the focus on the natural world, to name a few—are reflections of a Celtic-rooted past [Silva, 2015].

Camino do Santiago (Way of St. James)

Image Citation: stephenD [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catedral_de_Santiago_de_Compostela_agosto_2018.jpg

The story of Camino de Santiago, the Way of St. James, originates in the 9th century. The story explains that the body of St. James of Compostela was buried in Galicia by his disciples after his death in the 1st century. After this tomb was rediscovered in 814, King Alfonso II ordered a small chapel be built to draw pilgrims to the land and to rival other major holy sites [Phillips, W.D. & Phillips, C.R., 2011: 58-59; D’Emilio, 2015: 7-10]. The pilgrims' journey to this chapel, Santiago de Compostela, opened Galicia to the rest of the Europe, bringing the Asturian and, later, Leonese, monarchies into contact with the outside world.

Construction of the present-day cathedral began in 1075 and the importance of the structure as a holy site fueled pilgrimages from all around Europe. During the 12th and 13th centuries, it is estimated that 250,000 pilgrims visited the site annually [Camino Ways, n.d.]. However, the Reformation and the religious wars of the 14th and 15th centuries led to a decline in the number of pilgrims, and travelers did not return to the Camino de Santiago in the same numbers until the 1900s [Phillips, W.D. & Phillips, C.R., 2011: 58; Varela, 2020]. Today, the Camino de Santiago has multiple routes throughout Western Europe and the Iberian Peninsula that are popular with hikers. The existence and upkeep of the paths reflects the popularity and importance of this destination, both economically and culturally, for Galicia [Camino Ways, n.d.]. This most recent revival of the pilgrimage tradition began in the 1980s and 1990s, and, in 2018, 327,000 individuals received their Compostela (a certificate of completion) from their travels [Varela, 2020].

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

1. Genealogy/Relatedness

Galician (Galego) is a Romance language in the Western Ibero-Romance branch and derives from Latin. It is the official language in Galicia, and is also spoken in the neighboring autonomous communities of Asturias and Castile and León, near their borders with Galicia.

The Galician language, unlike Catalan, did not develop as a variant of Spanish. Initially, Galician and Portuguese were a single language prior to the severance of Portugal from Galicia at the end of the 11th century [Warf & Ferras, 2015: 260]. In many books of medieval verse they were considered as, and are still known today, as Galician-Portuguese. By the end of the 12th century, the histories of Galicia and Portugal had thoroughly separated [D’Emilio, 2015: 362-364; Warf & Ferras, 2015: 260].

2. Phonetics/Phonology

Galician includes seven vowel phonemes /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/ similar to Catalan and Italian [Regueira, 1996], and 19 consonants, whereas Spanish includes five vowels /i, u, e, o, a/ and 20 consonants [Martínez Celdrán et al., 2003].

3. Morphology and Grammar

In Galician, like Spanish, all articles, adjectives, nouns and pronouns are classified according to their gender as masculine or feminine, and according to their number as singular or plural. There are formal and informal forms of pronouns: the informal ti (second person singular) and vós (second person plural), and the formal vostede (second person singular) and vostedes (second person plural). Galician verbs are comprised of a stem, a stem-vowel and endings that correspond to mood-tense and number-person. Galician syntax is typical of southern Romance languages, and the canonical word order is subject-verb-object (SVO) [Freixeiro & Ramón, 2006].

4. Lexicon and Vocabulary

The Galician lexicon includes many words of Germanic origin, which were introduced into the language during the late antiquity, either as words that were borrowed into Vulgar Latin from elsewhere, or as words brought by the Suebi who settled in Galicia in the 5th century, or by the Visigoths who annexed the Suebic Kingdom in 585. Many other words were introduced into Galician during the Middle Ages from French and Occitan languages, as these cultures had a significant influence in Galicia during the 12th and 13th centuries. More recently other words were borrowed either from English or other Germanic languages or from Spanish, Portuguese, Italian or French. Most of this borrowed vocabulary in Galician is shared with Portuguese, although some spelling and phonetic differences are present [Ferreiro, 2001; Kremer, 2004].

5. Orthography/Writing System

The Galician alphabet includes 23 letters and six digraphs (ch, gu, ll, nh, qu, rr). There are also a group of letters (j, k, w, and y) that are only used in foreign loan words.

The modern official Galician orthography is based on the Orthographic and Morphological Norms of the Galician Language (1982), introduced by the Royal Galician Academy [Orthographic and Morphological Norms of the Galician Language, 2012]. In 2003, the Royal Galician Academy modified the language norms to promote some Galician-Portuguese forms that occur in modern Portuguese, hence supporting the reintegrationist perspective (which is a view that considers Galician to be a variant of Galician-Portuguese, as evidenced by the common origin, grammar, syntax, vocabulary, morphology and overall high level of mutual intelligibility). Today, that modified orthography is used by the government, majority of the media, cultural production and education.

6. Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

The linguistic history of the Galician language is rooted in its borders and its relationship with Castile and Portugal. Prior to the 8th century, the region was inhabited by Celtic peoples who spoke what are now-extinct Celtic languages. However, only a few lexical traces of this previous group remain in the modern Romance language Galician. Traces of Celtic influence are restricted to folklore, some individual vocabulary items, and some regional traditions. As speakers of Romance languages (i.e. linguistic descendants of Latin speakers) migrated into this region, Galician-Portuguese, the precursor language for Galician, began to develop.

Galician-Portuguese remained a single language until the division of the territory in the 11th century. While Galician is widely associated today with rural parts of Galicia, it was historically connected more with the higher classes and the literary arts; Alfonso X of Leon wrote his court documents in Castilian, but he wrote his poetry in Galician-Portuguese [D’Emilio, 2015: 64; Rodriguez, 2017]. Many of the troubadours of the period, most of them outside of the regions that form modern Galicia and Portugal, also used the language in their art.

After the 13th and 14th centuries, Galician went into decline. As Castilian Spanish became the language of court and official matters, Galician became the language of the countryside [Keating, 2001: 227; Fernández Rei, 2019: 440]. There was, and still is, some resistance to this decline, with efforts on the part of both the local educational establishment and local government to promote its use, as demonstrated in the rise of institutions such as the Royal Galician Academy and Radio Galega. Even in its own region, however, the position of Galician remains somewhat precarious. The rise of Spanish-Galician bilingualism and and the influx of monolingual Spanish speakers into Galicia proper has led to a decline in individuals who claim Galician as their first language [O’Rourke & Ramillo, 2015: 148-150; Fernández Rei, 2019: 441, 447-448].

There are today two dominant linguistic positions taken with respect to the Galician language: the isolationist view and the reintegrationist view. Isolationists consider Galician and Portuguese to be two distinct languages, although closely related. Those holding this position seeks to maintain different sets of writing and spelling rules for Galician and Portuguese, adhering more closely to traditional Spanish orthography combined with traditional Galician orthographic conventions. This is the position taken by the majority of the Galician public and the local government and its institutions, including Royal Galician Academy and the Institute for Galician Language [Minahan, 2000; Venâncio, 2006].

Reintegrationists consider Galician to be a variant of Galician-Portuguese, as evidenced by their common origins, grammatical features, vocabulary, morphology and mutual intelligibility. Those having this view of Galician-Portuguese support the use of orthographic conventions that are most similar to Portuguese. This view is supported by the Galician Association of the Language, Galician Academy of the Portuguese Language, Brazilian Academy of Letters, Lisbon Academy of Sciences, along with a number of other civic and cultural associations both in Galicia and in Portuguese-speaking countries. Supporters of the reintegrationist view hold that modern Portuguese originated in what is today Galicia, and therefore are in favor of stronger cultural and economic ties between Galician and Portuguese-speaking regions using a single language that is shared by both [Minahan, 2000; Venâncio, 2006].

Resources

A Bandeira Galega. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2020, from http://www.bandeiragalega.com/pt/galega.htm.

A Mesa pola Normalización Lingüística [The Bureau for Linguistic Normalization]. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://www.amesa.gal/quen-somos/queremos-galego.

Alberro, M. (2008). Celtic Legacy in Galicia. e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, 6(20). Retrieved from https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol6/iss1/20/.

Bahrami, B. (2003, March 15). The Modern Celts of Northern Spain. Retrieved February 25, 2020, from https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-modern-celts-of-northern-spain/.

Beswick, J. (2007). Regional Nationalism in Spain: Language Use and Ethnic Identity in Galicia. Multilingual Matters.

Boissoneault, L. (2014, January 27). The Mysterious Seventh Celtic Nation: Galicia, Spain. Retrieved February 25, 2020, from https://weather.com/travel/news/mysterious-seventh-celtic-nation-galicia-spain-20140127.

Byers, A. (2016). Strategic inventions of the Spanish Civil War. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/southcarolina/reader.action?docID=5404950.

Camino Ways. (n.d.). What is the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain? Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://caminoways.com/camino-de-santiago.

CIA. (2021, June 15). The World Factbook: Spain. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/spain/.

Consello da Cultura Galega [Galician Culture Council]. (n.d.) From the Origins to the Renaissance (6th century to 1475). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia.php?idioma=2&id=69

Consello da Cultura Galega [Galician Culture Council]. Galician Today. (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia.php?idioma=2&id=76.

Consello da Cultura Galega. (n.d.). From The "Rexurdimento" To The "Xeración Nós". Language, Literature, Identity (1863-1936). Retrieved July 27, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia.php?idioma=2&id=74.

Consello da Cultura Galega. (n.d.). History. Retrieved February 14, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia_pr.php?idioma=2&seccion=34.

Consello da Cultura Galega. (n.d.). The Franco Period (1936-75). Retrieved July 27, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia.php?idioma=2&id=75.

Consello da Cultura Galega. (n.d.). The Awakening of the Minorities. From a Vernacular to a National Language. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from http://consellodacultura.gal/cdsg/loia/historia.php?idioma=2&id=72.

Constitute. (n.d.). Spain's Constitution of 1978 with Amendments through 2011. (n.d.). Retrieved December 21, 2019, from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Spain_2011.pdf?lang=en.

CRTVG. (n.d.). Presentación da Corporación Radio e Televisión de Galicia – CRTVG [Presentation of the Galician Radio and Television Corporation - CRTVG]. Retrieved January 31, 2020, from http://www.crtvg.es/crtvg/presentacion/a-crtvg/idioma/eng.

D'Emilio, J. (2015). Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia: A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe (Vol. 58, The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World). Leiden: Brill. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/southcarolina/reader.action?docID=2110721.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2015, November 20). Galician language. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Galician-language.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020, January 28). Rosalía de Castro. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rosalia-de-Castro.

Ellis, P.B. (1993). The Celtic dawn: A history of Pan Celticism. Constable.

Eurostat. (2021, May 19). Regional gross domestic product by NUTS 2 regions - million EUR. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tgs00003/default/table?lang=en.

Fatu-Tutoveanu, A., & Álvarez, R. J. (with Healy, A.) (Eds.). (2013). Press, propaganda and politics: Cultural periodicals in Francoist Spain and Communist Romania.

Ferreiro, M.(2001). Gramática histórica galega (v. 2) (2nd ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Eds. Laiovento.

Fernández Rei, E. (2019). Galician and Spanish in Galicia: Prosodies in contact. Spanish in Context, 16(3), 438–461. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1075/sic.00046.fer.

Freixeiro, M., & Ramón, X. (2006). Gramática da lingua galega (I). Fonética e fonoloxía (in Galician). Vigo: A Nosa Terra.

Galicia Guide. (n.d.). A few facts about Galicia Spain. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from http://www.galiciaguide.com/Galicia-facts.html.

Galician Today. (n.d.). Galicia in the World. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from http://www.galego.org/english/today/world.html.

Herbert, K. (2014, January 22). Travel - Where is the seventh Celtic nation? Retrieved February 25, 2020, from http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20131203-where-is-the-seventh-celtic-nation.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. (Spanish Statistical Office). (n.d.). Demographic phenomena, by Autonomous Cities and Communities and type of demographic phenomenon. Retrieved September 10, 2020, from https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=6567.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. (Spanish Statistical Office). (n.d.). Population mortality tables for Spain by year, sex, age and functions. Retrieved September 10, 2020, from https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=27153.

Keating, M. (2001). Rethinking the Region: Culture, Institutions and Economic Development in Catalonia and Galicia. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(3), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640100800304.

Keeley, G. (2008, May 3). Spanish speakers fight to save their language as regions have their say. Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/may/04/spain.

Kremer, Dieter (2004). “Galicia germânica.” In: Rosario Álvarez Blanco, Francisco Fernández Rei, Antón Santamarina (ed.). A Lingua Galega: Historia e Actualidade. Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega, 9-25.

Language Magazine. (2019, November 12). The challenges of minority languages: 1 in 4 children cannot speak Galician in Galicia Spain. Retrieved June 28, 2021, from https://www.languagemagazine.com/2019/11/12/the-challenges-of-minority-languages-1-in-4-children-cannot-speak-galician-in-galicia-spain/.

Leerssen, J. (2015). The nation and the city: urban festivals and cultural mobilisation. Nations & Nationalism, 21(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12090

Lingua. (n.d.). Basic Data on Galician Language. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.lingua.gal/to-know/basic-data-on-galician-language.

Lombao, D. (2012, December 12). O Apalpador lémbralle a Feijóo a obriga legal de protexer o galego no ensino [The Palpador reminds Feijóo of the legal obligation to protect Galician in education]. Retrieved April 1, 2020, from https://praza.gal/movementos-sociais/o-apalpador-lembralle-a-feijoo-a-obriga-legal-de-protexer-o-galego-no-ensino

Martínez Celdrán, E., Fernández Planas, A. M., & Carrera Sabaté, J. (2003). Castilian Spanish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33(2): 255-259.

McIntyre, E. (2013, December 11). Celtic Identity, Language and the Question of Galicia. Retrieved February 25, 2020, from https://www.transceltic.com/pan-celtic/celtic-identity-language-and-question-of-galicia.

Minahan, J. (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 279.

Minority Rights Group International. (n.d.). Galicians. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://minorityrights.org/minorities/galicians/

Nandi, A. (2018). Language Policies and Linguistic Culture in Galicia. LaborHistórico, 3(2), 28. doi: 10.24206/lh.v3i2.17124. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/149625787/Language_Policies_and_Linguistic_Culture_in_Galicia.pdf.

Newcomb, R. P. (2017). Iberianism and Crisis: Spain and Portugal at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

Normas ortográficas e morfolóxicas do idioma galego [Orthographic and Morphological Norms of the Galician Language] (in Galician) (23rd ed.). Real Academia Galega. March 2012.

O’Rourke, B. (2003). Conflicting values in contemporary Galicia: attitudes to “O Galego” since autonomy. International Journal of Iberian Studies, 16(1), 33–48. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1386/ijis.16.1.33/0.

O’Rourke, B. (2018). Just use it! Linguistic conversion and identities of resistance amongst Galician new speakers. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 39(5), 407. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=129754788&site=eds-live.

O’Rourke, B., & Ramallo, F. (2015). Neofalantes as an active minority: understanding language practices and motivations for change amongst new speakers of Galician. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, (231), 147. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1515/ijsl-2014-0036.

Parlamento de Galicia [Galician Parliament]. (1983). Ley 3/1983, de 15 de junio, de normalización lingüística [Law 3/1983, of 15 June, on linguistic normalization]. Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved from https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1983/DOG-g-1983-90056-consolidado.pdf.

Patterson, C. (2006). A tale of two identities: Spanish intercultural dialogue in Toledo. The Modern Language Review, 2, 414.

Pena, M. P. (2019, March 31). La larga búsqueda de los restos del último alcalde republicano de Amoeiro se completa con su exhumación [The long search for the remains of the last Republican mayor of Amoeiro is completed with his exhumation]. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.eldiario.es/galicia/Amoeiro_0_883661753.html.

Pérez, J. I., Gómez, A. M. G., & Atkinson, W. C. (2019, February 10). Galician literature. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/art/Spanish-literature/Galician-literature.

Pérez‐Sanjulián, C. F. (2010). A Xeración Nós. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.aelg.gal/resources/centrodoc/members/paratexts/pdfs/autor314/PT_paratext2984.pdf.

Phillips, W. D., & Phillips, C. R. (2010). A Concise History of Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=490553&site=ehost-live .

Plataforma Queremos Galego! [We Want Galician Platform!] (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://www.queremosgalego.gal/.

Queremos Galego [We Want Galician]. (2019, December 13). Queremos Galego sae á rúa perante a situación de emerxencia lingüística para esixir que a Xunta e o Estado cumpran coas demandas do Consello de Europa [Queremos Galego takes to the streets in the face of a linguistic emergency to demand that the Xunta and the State comply with the demands of the Council of Europe]. Retrieved March 18, 2020, from https://www.queremosgalego.gal/2019/12/13/queremos-galego-sae-a-rua-perante-a-situacion-de-emerxencia-linguistica-para-esixir-que-a-xunta-e-o-estado-cumpran-coas-demandas-do-consello-de-europa/.

Regueira, X. L. (1996). Galician. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 26(2): 119–122.

Rodgers, E. J. (1999). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Spanish Culture. Routledge.

Rodriguez, V. (2011, August 26). Asturias. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Asturias-region-Spain.

Rodriguez, V. (2017, November 9). Galicia. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Galicia-region-Spain.

Roseman, S. (1996). "How We Built the Road": The Politics of Memory in Rural Galicia. American Ethnologist, 23(4), 836-860. Retrieved April 2, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/646186.

Screti, F. (2018). Re‐writing Galicia: Spelling and the construction of social space. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 22(5), 516–544. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1111/josl.12306.

Share, D. (1986). The Franquist Regime and the Dilemma of Succession. The Review of Politics, 48(4), 549-575. Retrieved July 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1407383.

Silva, C. V. (2015, May 30). Galicia: the unknown 7th Celtic nation. Retrieved February 25, 2020, from https://wsimag.com/travel/15461-galicia-the-unknown-7th-celtic-nation.

Statistical Institute of Catalonia [Idescat]. (2020, December 23). Population on 1 January. By sex. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10328&lang=en&tema=xifpo&t=202000.

The Galician National Flag. (n.d.). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from http://www.galicianflag.com/galicia.htm.

Thousands demand "total change" in Galicia's language policy. (2015, February 9). Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://www.nationalia.info/new/10456/thousands-demand-total-change-in-galicias-language-policy.

Townson, N. (with Seidman, M.) (Eds.) (2015). Is Spain Different?: A Comparative Look at the 19th and 20th Centuries. Sussex Academic Press.

Varela, M. G. (2020, January 17). The History of the Camino de Santiago. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://caminoways.com/the-history-of-the-camino-de-santiago.

Venâncio, F. (2006). “I see my language everywhere:” On linguistic relationship between Galicia and Portugal.

Warf, B., & Ferras, C. (2015). Nationalism, identity and landscape in contemporary Galicia. Space & Polity, 19(3), 256–272. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1080/13562576.2015.1080425.

Xunta de Galicia. (n.d.). Alfonso Daniel Rodríguez Castelao. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://emigracion.xunta.gal/es/conociendo-galicia/aprende/biografia/alfonso-daniel-rodriguez-castelao.

Xunta de Galicia. (2009, January 10). Estatuto de Autonomía de Galicia - Título Preliminar [Statute of Autonomy of Galicia - Preliminary Title]. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.xunta.gal/estatuto/titulo-preliminar.

Xunta de Galicia. (n.d.). Símbolos de Galicia [Symbols of Galicia]. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.xunta.gal/a-bandeira.

Zenith, R. (2004, July 9). An Unsung Literature. Retrieved February 13, 2020, from https://www.poetryinternational.org/pi/article/4621/An-Unsung-Literature/en/tile.

Images, in order of appearance

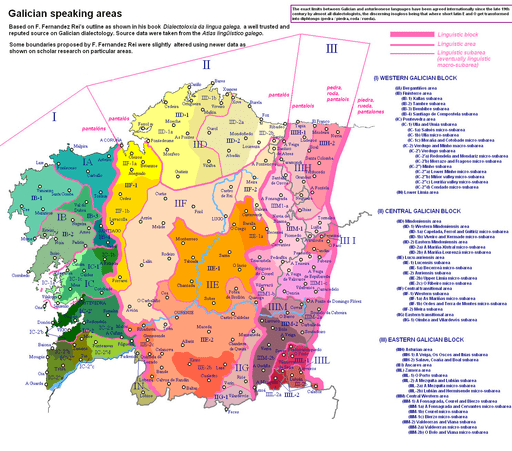

Susana Freixeiro, Map of Galician Speaking Areas, June 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galician_linguistic_areas.PNG.

Bene Riobó [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Insua_dos_Poetas,_Rexurdimento.jpg

regueifeiro [CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carnet_das_Irmandades_da_Fala_de_1917.jpg

Asamblea Regional de Ayuntamientos. [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Estatuto_de_Galicia_de_1936.pdf

Soler, P.F. (User: Forcy) [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Valle_de_los_caidos_by_forcy-cruz_y_basilica.jpg

Xesús Canabal, Castelao e Manuel Meilán, Montevideo, 1940.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49962636

Pedro A. Gracia Fajardo. Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Galicia.svg

Merixo / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:50c86a53b31c1-2012-Queremos_Galego-Praza_P%C3%BAblica-2012.jpg

stephenD [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catedral_de_Santiago_de_Compostela_agosto_2018.jpg

BzhSamTheRipper . (2010, August 20). File: Combined flag of the Celtic nations.jpg. Retrieved February 25, 2020, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Combined_flag_of_the_Celtic_nations.jpg.

Credits

Posted: 30 July 2021

Previous versions: Feb 2020

Contributing Analysts: Will Stallings

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina