Conflict Type

Peak Years

Intensity

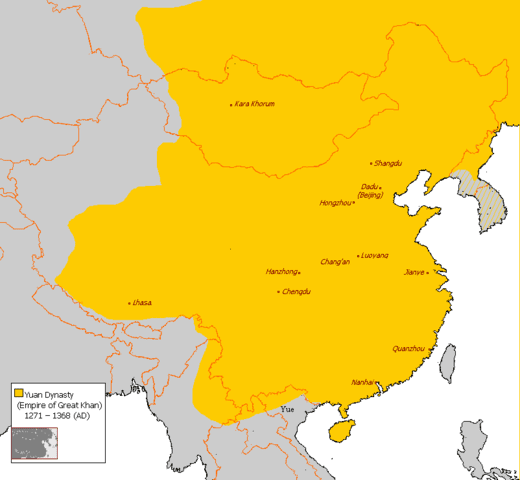

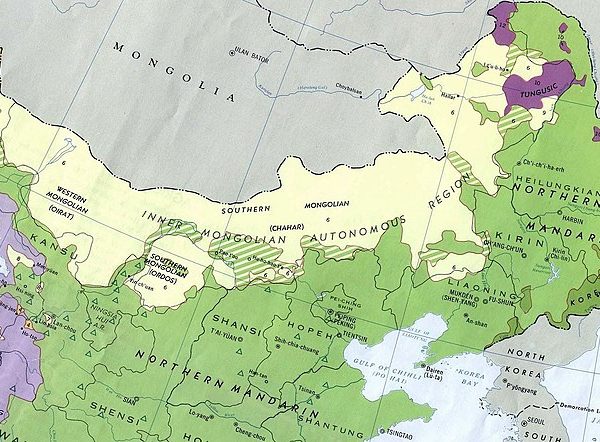

The indigenous minority language conflict between the Mongol and Han Chinese ethnic groups in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region stretches over thousands of years. In 1279, during the expansion of the Mongol empire, Khubilai Khan completed the Mongol conquest of China. The Mongols would only rule China until 1368 before the fall of the Yuan Dynasty. Over the next 700 years, the Mongols fell under the control of China. While the nation of Mongolia was established in the 20th century, the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region (IMAR) in southern Mongolia remained part of China. Today, Han Chinese outnumber Mongols in Inner Mongolia by 5 to 1. Forced resettlement to urban areas and environmental degradation of the grasslands because of mining industry expansion have endangered the traditional Mongol pastoral lifestyle, and Mongols have lost much of their cultural and linguistic identity. Today the conflict is minimally violent, with protests occasionally breaking out in IMAR.

Historical Background

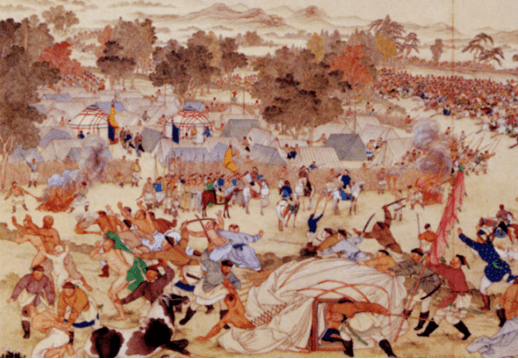

By 1205 CE the various Mongol nomadic tribes inhabiting areas of the present-day Mongolia and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region had been united under the leadership of Mongol leader Genghis Khan [History.com Editors, 2019]. In the years following this unification, the conquests of Genghis Khan and his descendants led to the rapid expansion of land under Mongol rule, eventually establishing the Mongol empire as the largest contiguous land empire in history, stretching from Poland to Vietnam [History.com Editors, 2019]. In 1279, Kublai Khan completed the Mongol conquest of China, placing it under the Yuan dynasty [Bawden, 2019], which lasted until 1368 [The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017]. In the early 1600s, the Qing Dynasty of China (presided over by the Manchu ethnic group) conquered the areas of modern-day Mongolia and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and the Mongolic people came under Chinese rule [Carlson, 2013].

In 1911, shortly before the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, Outer Mongolia declared its independence from China [Harris, Sanders, & Lattimore, 2019]. Efforts to unite Inner Mongolia with the newly formed nation Mongolia were unsuccessful, however, and Inner Mongolia remained part of China [Harris, Sanders, & Lattimore, 2019]. The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) was established as a semi-autonomous province of China in 1947 [Falkenheim & Cheng, 2019]. During the Cold War, the rift between the people of Mongolia and those of Inner Mongolia intensified as Mongolia became a satellite state of the Soviet Union [Radchenko, 2007]. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was increasing tolerance and promotion of the Mongolian language, with the provincial leader of the IMAR, Ulanhu, calling for the establishment of a large-scale Mongolian language education program in IMAR, albeit to better propagate Mao Zedong Thought amongst Mongolian speakers [Bulag, 2003]. This trend was, however, reversed during the Cultural Revolution, when use of the Mongolian language became stigmatized and a program for the aggressive promotion of Mandarin in the IMAR was established [Bulag, 2003]. Following the Cultural Revolution, IMAR’s economy improved rapidly. In more recent years, however, the growth of the mining industry in IMAR and the ecological damage it has caused in the surrounding grasslands has forced Mongolian herders to abandon their traditional pastoral lifestyle and move to urban areas [WW4 Report, 2013; Jacobs, 2011].

Chinese impediments to Mongolian speakers in a Mongolian airport

In April 2016, an ethnic Mongolian grandmother traveled with her son and grandson to an airport in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Only the grandson had any fluency in Mandarin, and the grandmother and her son could only speak Mongolian. The announcements for when their flight was boarding were spoken in Chinese and English, but the grandson was not present when the announcement was made. The family eventually realized that their flight was boarding and rushed to the gate but were delayed after security officers forced the grandma to remove her scarf and winter coats, itself a potential case of racial profiling, as she was only one wearing traditional Mongolian garb [Baioud, 2018]. They missed their flight.

When her grandson went to complain to the service desk, they were told that in Inner Mongolia they speak Chinese and English as official languages, not Mongolian. This remark directly contradicts guidelines and regulations governing the use of Mongolian in Inner Mongolia that make clear that Mongolian should be used in all public institutions, including airports [Baioud, 2018]. The airport eventually apologized to the family and reimbursed them for their flight and committed to issue announcements in Mongolian alongside English and Chinese.

An ethnic Mongolian graduate student at Macquarie University in Australia makes the claim that this incident – specifically, the use of English in Inner Mongolia over the use of the much more common and indigenous Mongol language - represents the interests of the public, being subordinated to the economic interests of the elites. The public use of Mongolian is the last “token degree of autonomy” that the ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia have, so taking that away, in the opinion of many Mongolians, essentially destroys their last claim to their homeland [Bulag qtd. in Baioud, 2018].

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

Genealogy/Relatedness

The Mongolian language is a member of the Altaic language family and the Mongolian languages subfamily. It is spoken by around 7 million people in both Mongolia and China (including the regions of Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia). It is most closely related to Oirat, Kalmyk, and Buryat (all part of the Mongolian language sub-family) [Binnick, 2011].

Mandarin is a member of the Sino-Tibetan language family [Egerod, 2013]. Mandarin is the most widely spoken Chinese language, estimated to be spoken by 917 million people [Lane, 2019]. It is one of the oldest written languages in the world having been written for over 3,000 years [Lin, 2019].

Phonetics/Phonology

Mongolian includes seven vowels, which are grouped into three vowel harmony categories using an ATR1 (advanced tongue root) parameter, where the groups are −ATR, +ATR, and neutral. The Mongolian vowel system also has rounding harmony.2 Length is phonemic for vowels, and each of the seven vowel phonemes can be short or long, making for 14 vowel contrasts. Mongolian includes 34 consonant phonemes, five of which are present only loanwords. Mongolian lacks the voiced lateral approximant [l] and the voiceless velar plosive [k], which are present in most world’s languages [Svantesson et al., 2005].

Mandarin includes five vowels and 22 consonants [Lin, 2007]. It is a tonal language with four tones: high level, rising, dipping (falling-then-rising), and falling, used to distinguish between morphemes that otherwise have the same string of vowels and consonants, but different meanings [The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2014]. This is one of biggest differences between Mandarin and Mongolian.

Morphology and Grammar

Mongolian is an agglutinative language3. Nouns do not have gender or definiteness but can conjugate in eight cases: nominative (unmarked), genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, instrumental, comitative and directional [Janhunen, 2012]. Unmarked phrase order is subject-object-verb (SOV). While the verb generally has to remain in clause-final position, the other phrases are free to change order [Tserenpil & Kullmann, 2005].

Mandarin is an analytic language4 and does not use inflection. Categories such as number (singular or plural) when expressed and verb tense and aspect generally employ wordlike particles that are similar in their distribution to English prepositions. The basic word order is subject-verb-object (SVO). Like other East Asian languages, Mandarin uses classifiers with numerals and demonstratives with nouns. There are quite a few different classifiers, each used in combination with numeral and nouns of a particular class. For instance, counting two long thin objects (such as sticks or pens) would involve the classifier zhi and be 2-zhi, while two flat objects (such as book) would involve ben and be 2-ben [Ross & Jing-Heng Sheng, 2006].

Lexicon and Vocabulary

Mongolian borrowings include words from Old Turkic, Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, Tibetan, Tungusic, and Chinese. More recent loanwords are borrowed from Russian, English, and Mandarin Chinese, the last primarily in Inner Mongolia. In the 20th century Mongolian acquired numerous Russian loanwords pertaining to daily life (e.g., doktor (‘doctor’), vagon (‘train wagon’), and mashin (‘car’). More recently, due to socio-political changes, Mongolian has borrowed various words from English (e.g., menejment, computer, onlain (‘online’), and mesej (‘message’) [Janhunen, 2003].

The majority of Mandarin words are created out of native Chinese morphemes, including words describing foreign objects and ideas, but phonetic borrowings exist as well. Some words were borrowed from Sanskrit or Pāli, the languages of North India, while others came from Altaic languages of nomadic people of the Gobi, Mongolian or northeast regions [Kane, 2006]. In 20th century, Japanese became the source of borrowings related to modern technology [Chung, 2001].

Orthography/Writing System

The traditional Mongolian script was adapted from Uyghur script (i.e., a script used between the 8th and 17th centuries primarily in the Tarim Basin of Central Asia, located in present-day Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Its features are similar to abjad and it is written vertically) approximately at the beginning of the 13th century. An attempt was made to introduce the Latin script in the Mongolian state (i.e., in the Soviet-influenced independent state of Mongolia) between 1930 and 1932, and although, the Latin alphabet was adopted in 1941, it lasted only several months. Russian influence at the time resulted in the development of the Mongolian Cyrillic script, which was made mandatory by government in 1941 [Svantesson et al., 2005].

One of the main divides that exists between Inner Mongolia and Mongolia is written script. Mongolia uses the Cyrillic alphabet, while in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Mongolian is written in the Classical Mongolian script [Center for Languages of the Central Asian Region, 2019]. The Classical Mongolian script is written vertically from top to bottom, while the Cyrillic script is written horizontally from left to right [The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2012].

In 2020, the Mongolian government announced plans to use both Cyrillic and the traditional Mongolian script in official documents by 2025 [China.org.cn, 2020].

Image: Vowels in Traditional Mongolian script, Cyrillic and Latin-based scripts (Retrieved 15 July 2021 from https://omniglot.com/writing/mongolian.htm)

Image: Consonants in Traditional Mongolian script, Cyrillic and Latin-based scripts (Retrieved 15 July 2021 from https://omniglot.com/writing/mongolian.htm)

Image: Consonant/vowel combinations in Traditional Mongolian script, Cyrillic and Latin-based scripts (Retrieved 15 July 2021 from https://omniglot.com/writing/mongolian.htm)

Traditionally, Mandarin was written in a character script read in columns from top to bottom, with the columns ordered from right to left. In modern contemporary usage, texts are printed in rows, read from left to right, like English. Each Chinese character represents a monosyllabic Chinese word or morpheme, and these characters can be classified into six categories (i.e., pictographs, simple ideographs, compound ideographs, phonetic loans, phonetic compounds and derivative characters). Currently, there are two writing systems identified for Chinese characters. The traditional system, mainly used in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Chinese speaking communities (except Singapore and Malaysia) outside mainland China, uses characters that are both more complex and more transparent in their meaning and pronunciation, since they are comprised of elements that have been stable for centuries (mostly keeping forms that date back to the late Han dynasty, 200 CE). The Simplified Chinese character system, introduced by the People’s Republic of China in 1954 to promote mass literacy, simplifies most complex traditional characters to fewer strokes, and in so doing destroys much of the logic and transparency of the traditional system [Qiu, 2000] While the official rationale for simplification was to promote literacy, in practice simplification provided a way for the Chinese Communist Party to make pre-Communist Chinese texts difficult or impossible for people to read, thus severing the Chinese people’s ability to read and understand prerevolutionary texts.

Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

Both Mongolian and Mandarin are the official languages of the Inner Mongolia, although in practice Chinese authorities often do not respect Mongolian’s official status and suppress its use when they can. The use of Mongolian language in China, specifically Inner Mongolia declined during the late Qing period (1636–1912), increased between 1947 and 1965, declined again between 1966 and 1976, increased again between 1977 and 1992, and declined for the third time between 1995 and 2012 [Tsung, 2014]. Despite the more recent declines in language use, the ethnic Mongols continue to try to preserve their language and identity [Janhunen, 2012].

Resources

References

Baioud, G. (2018, April 18). Is English stealing the home of Mongolian? Retrieved from Language on the Move website: https://www.languageonthemove.com/is-english-stealing-the-home-of-mongolian/

Bawden, C. (2019). Kublai Khan. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Kublai-Khan.

Binnick, R. (2011). Mongolian Languages. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mongolian-languages

Binnick, R. (2011). Mongolian Languages. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mongolian-languages

Bulag, U. (2003). Mongolian Ethnicity and Linguistic Anxiety in China. American Anthropologist, 105(4), 753–763.

Carlson, B. (2013, March 6). Why China is crushing a Mongolian intellectual. Retrieved from CBS News website: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/why-china-is-crushing-a-mongolian-intellectual/.

Center for Languages of the Central Asian Region. (2019). Who are Mongols and where do they live?. Retrieved from https://celcar.indiana.edu/materials/language-portal/mongolian/index.html

Center for Languages of the Central Asian Region. (2019). Who are Mongols and where do they live?. Retrieved from https://celcar.indiana.edu/materials/language-portal/mongolian/index.html

Chung, K. S. (2001). Some Returned Loans: Japanese Loanwords in Taiwan Mandarin. In McAuley, T.E. (ed.). Language Change in East Asia. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. pp. 161–179.

Egerod, S. (2013). Chinese Languages. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-languages

Egerod, S. (2013). Chinese Languages. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chinese-languages.

Falkenheim, V., & Cheng, C. (2019). Inner Mongolia. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Inner-Mongolia.

Harris, C., Sanders, A., & Lattimore, O. (2019). Mongolia. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Mongolia.

History.com Editors. (2019, June 6). Genghis Khan. Retrieved from: https://www.history.com/topics/china/genghis-khan

Inner Mongolia. (2019). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Mongolia

Jacobs, A. (2011, June 10). Ethnic Protests in China Have Lengthy Roots. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/11/world/asia/11mongolia.html.

Janhunen, J. (2003). The Mongolic Languages. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge.

Janhunen, J. (2012). Mongolian. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Janhunen, J. (2012). Mongolian. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Kane, D. (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage. Tuttle Publishing.

Ladefoged, P. & Maddieson, I. (1996). The Sounds of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lane, J. (2019, September 6). The 10 Most Spoken Languages in the World. Retrieved from https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/the-10-most-spoken-languages-in-the-world.

Lane, J. (2019, September 6). The 10 Most Spoken Languages In The World. Retrieved from https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/the-10-most-spoken-languages-in-the-world.

Liebertha, Kl. (2019). Cultural Revolution. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Cultural-Revolution/Rise-and-fall-of-Lin-Biao-1969-71.

Lin, K. (2019). Chinese Language. Retrieved from: https://ethnomed.org/culture/chinese/chinese-language-profile.

Lin, K. (2019). Chinese Language. Retrieved from: https://ethnomed.org/culture/chinese/chinese-language-profile.

Lin, Y.-H. (2007). The Sounds of Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Minority Rights Group International. (2017, November). Mongols. Retrieved from: https://minorityrights.org/minorities/mongols/

Mongolia to promote usage of traditional script (2020). Retrieved from china.org.cn.

Mongolian language. (2019). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mongolian_language

Qiu, X. (2000). Chinese Writing, trans. Gilbert Louis Mattos and Jerry Norman. Society for the Study of Early China and Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

Radchenko, S. (2007). New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War. Cold War International History Project Bulletin, (16). Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/CWIHPBulletin16_p4.pdf.

Ross, C. & Jing-Heng Sheng, M. (2006). Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar: A Practical Guide. Routledge.

Rossabi, R. (2004). What was the Mongols’ influence on China? Retrieved from The Mongols in World History website: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/china/china.htm.

Svantesson, J.-O., Tsendina, A., Karlsson, A., Franzén, V. (2005). The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2009). Agglutination. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/agglutination-grammar

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2011). Analytic language. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/analytic-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2012). Mongol Language. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mongol-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2012). Mongol Language. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mongol-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2014). Mandarin Language. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mandarin-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2014). Mandarin Language. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mandarin-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2017). Yuan Dynasty. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Yuan-dynasty.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019). Mongol Empire. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Mongol-empire

Tserenpil, D., & Kullmann, R. (2005). Mongolian grammar. Ulaanbaatar: Admon.

Tsung, L. (27 October 2014). Language Power and Hierarchy: Multilingual Education in China. Bloomsbury Academic.

WW4 Report. (2013, April 6). China: Mongol Herders’ Protest March Blocked. Retrieved from: https://intercontinentalcry.org/china-mongol-herders-protest-march-blocked/

Image Credits

Flag of the Inner Mongolian People’s Party, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Inner_Mongolian_People%27s_Party.svg, Public Domain

Flag of Mongolia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Mongolia.svg, Public domain

Battle Between Mongols and Chinese 1211, https://www.chinasage.info/mongol-dynasty.htm, Image by Sayf al-Vâhidî. Hérât

Drunzgar genocide, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dzungargenocide.png, public domain

Completely root out the Ulanfu reactionary clique, https://www.smhric.org/The%20Purge%20of%20the%20Heirs%20of%20Cenghis%20Khan.pdf, Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center

“In a region where protest is rare, more than 100 people on Monday took to the streets of Hohhot, the Inner Mongolian capital”, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/world/asia/31mongolia.html, Photographer Sim Chi Yin for NY Times

Inner Mongolia, China, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:China_Inner_Mongolia.svg, public domain

KFC in Hohhot, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KFC_in_Hohhot.jpg, Image owner: Colipon (Creative Commons)

“The website of Hohhot Baita International Airport provides information in Chinese and English but not in Mongolian”, https://www.languageonthemove.com/is-english-stealing-the-home-of-mongolian/, Image screenshot by Gegentuul Baioud

Credits

Posted: Sept 2021

Previous Versions:

Contributing Analysts: Tyler Jackson

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina