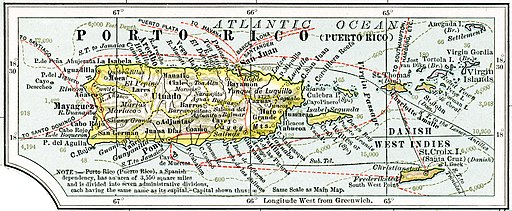

The language conflict on both the island of Puerto Rico and within mainland US Puerto Rican communities has been present since the United States gained control of the island from the Spanish in 1898. Prior to the colonial shift, Puerto Rico had been a Spanish speaking island for almost 400 years, before English was suddenly introduced in 1902. As such, this can be characterized as a geopolitical minority conflict: both English and Spanish have been official languages in Puerto Rico since 1902, but Spanish has always been the chosen language of the majority of the population and remains the language of official business on the island. There is also a large population of Puerto Ricans living in the mainland United States who face different challenges as full citizens confronted with the stigmas that come from being looked upon as immigrants because of their language. While people of the island fight to protect the Spanish language as their cultural heritage, many Puerto Ricans living on the mainland remain proud of their bilingual identities. Meanwhile, the debate over statehood for the island continues as it has for over a century.

Historical Background

Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico

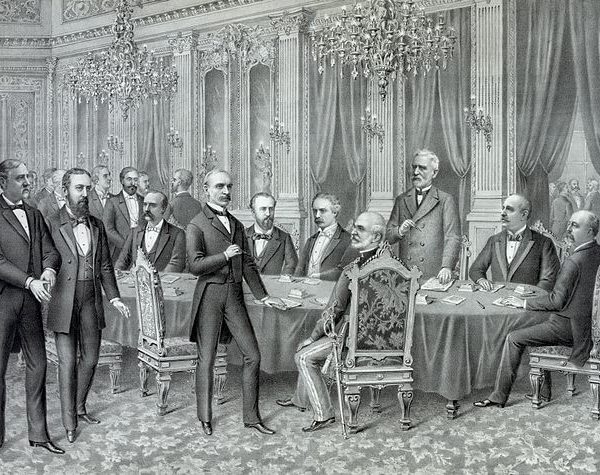

The United States acquired Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898 following the Spanish-American War, and Puerto Rico remains a US commonwealth today [Mathews, Wagenheim, & Wagenheim, 2021]. Puerto Ricans were granted US citizenship in 1917 as a result of the Jones-Shafroth Act, but the US did not permit them to elect their own governor and write their own constitution until 1950 [Mathews, Wagenheim, & Wagenheim, 2021].

Spanish continues to be the major language in Puerto Rico despite many efforts by the US to promote English to primacy, beginning with the 1902 Official Languages Act that declared both Spanish and English to be official languages of the island. This law was followed by a three decades-long movement pressuring Puerto Ricans to make English the official language of instruction in their schools and to add American history to the curriculum. Puerto Rican legislators have, for their part, tried to make Spanish the required language of instruction in public schools to protect themselves from the American encroachment in 1913, 1933, and again in 1947, but each effort was vetoed by the US officials [Davies & Dubinsky, 2018]. Today, 95% of the Puerto Rican population speaks Spanish, while only 20% speak English, and official business is conducted in Spanish.

As a result of the tensions created by American colonization, Puerto Ricans have long debated between forging for full independence, remaining a commonwealth, or becoming the 51st American state. A series of events, including the destruction caused by Hurricane Maria in 2017, has left the island with economic strife in comparison to the mainland United States. For example, in 2021 the island’s unemployment rate was 8.2% in May 2021, in comparison to the nations rate of 5.8% [U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021], while in 2019 the poverty rate was 43.5% in 2019, in comparison to a national rate of 10.5% [United States Census Bureau, 2019]. As such, while a small number of Puerto Rican nationalists have agitated for independence, it is commonly understood that this would strip the island of tax exemptions and federal subsidies, leaving an even more strained economic situation than at present. Due to this, the push for independence has never found broad support among the Puerto Rican population. The split between the other two options - remaining a commonwealth and being admitted to the US as the 51st state - can be largely attributed to language tensions. Many Puerto Ricans fear that assimilating into the US as a state would erase their Spanish language and culture, a fear given credence by the historical push the US has made to Americanize the island. There is also US resistance to Puerto Rican statehood. As well as Republican fears that the liberal-leaning island would offer its newly gained federal election votes disproportionately to Democrats. Finally, there is some concern that admitting a Spanish-speaking state to the Republic would mean the United States would officially become a bilingual country, threatening the place of English as the only national language [Newkirk, 2017].

In June 2017, the Puerto Rican government held a referendum asking people to vote on the statehood issue, and of the unusually low 23% of voters who showed up to the polls (due to widespread boycotts of the vote), 97% voted in favor of statehood [Newkirk, 2017; Robles, 2017]. Since then, Puerto Rico’s Congressional representative, Resident Commissioner Jennifer Gonzalez, has introduced a bill to make Puerto Rico a US state by 2021. In March of 2021, Representative Darren Soto (D-FL) introduced H.R.1522 - Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act to the US House of Representatives. Committee hearings are currently being held on the bill [Soto, 2021].

Puerto Ricans Living in the Mainland United States

Puerto Rican migration to the US did not begin in earnest until after WWII, when some 700,000 Puerto Ricans arrived on the mainland. The island’s population has declined a full 5% since 2010, due in part to an economic recession that triggered by a 2006 revision of the IRS tax code that caused a large drain of foreign direct investment (FDI) from the Puerto Rican economy [Berridge, 2015], and in part to the destruction wreaked by Hurricane Maria in 2017. As of 2021, twice as many (~5.8 million) Puerto Ricans live on the US mainland than do on the island itself. Puerto Ricans currently living on the US mainland constitute the second-largest US Hispanic group behind Mexicans. On the home island of Perto Rico, the 2021 population has dropped down to mid-1970s levels (~2.8 million) after peaking at approximately 3.6 million in around 2000 [United States Census Bureau, 2019].

Puerto Ricans’ political status as US citizens was frequently misunderstood, contributing to the suspicion and fear they have faced and continue to confront. As non-whites whose first language was not English, Americans tended to regard them as non-American immigrants, while being forced to reckon with the fact that Puerto Ricans held political power in the US as voting citizen-residents. This tension was most evident in New York City, where 90% of Puerto Ricans migrated in the post-WWII wave and where there still exist predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhoods like “El Barrio” or “Spanish Harlem” in New York City (which is roughly the area of Manhattan north of 96th Street and east of 5th Avenue) [Davies & Dubinsky, 2017]. Children who migrated with their families to the Northeast and Midwest faced perhaps the greatest challenge, as they were chronically underserved in English-language instruction in US schools, a fact which made their assimilation into and eventual economic success in the US an uphill battle.

Today, Puerto Ricans still face stigma in the United States: despite the fact that 83% of them are proficient in English, with fully 40% being English-dominant. The misperception of there being a language barrier (partly on account of their Spanish-accented but otherwise proficient English) often makes it “difficult [for them] to find well-paying work or to navigate agencies or other English-speaking institutions” [Library of Congress, 2018]. As is so frequently the case, language differences, such as Spanish-tinged English accents or the occasional use of Spanish “loan words” (i.e., code mixing) in English discourse, generates both implicit and explicit discrimination, in this instance directed even at American-born Puerto Ricans [Beardsley, 2004].

Puerto Rico on Broadway

The 1957 musical West Side Story, an enthusiastically received Broadway production with a book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, was inspired by Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and highlights issues of racism in urban New York through a tale of two feuding gangs, one white (“The Jets”) and one Puerto Rican (“The Sharks”). While the characters portraying the members of The Sharks do not speak or sing in Spanish, they do adopt some Spanish-speaker like English slang as they debate the differences between the island and New York City in the song “America”. West Side Story was nominated for multiple Tony Awards and inspired an Academy Award-winning movie. First made into a movie in 1961, a cinematic remake, directed by Stephen Spielberg, will be released in 2021.

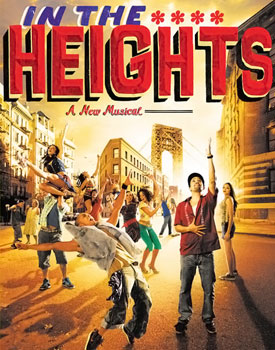

Lin Manuel Miranda’s 2008 Broadway musical In the Heights brought increased general attention to bilingual speakers in the United States. As a child of Puerto Rican parents, Miranda grew up in Washington Heights, a neighborhood in New York City with a large population of Hispanic-Americans. In the Heights features songs in a mix of English and Spanish with musical styles ranging from rap to salsa. The musical celebrates bilingualism, including one song - “Sunrise” - featuring one character teaching another Spanish as a way to express their love and uncertainty. Heights brought Miranda recognition and acclaim, winning many awards including the Tony Award for Best Musical.

Following In the Heights, Miranda rose to fame with the success of his next musical, Hamilton. He has become an outspoken advocate for Puerto Rico, although some have criticized him for publicly supporting policies like The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act despite having never lived on the island [Toole, 2018]. Nevertheless, Miranda used his fame to raise money for relief in Puerto Rico following the devastation of Hurricane Maria in 2017, including returning to star in a special run of Hamilton on the island with all proceeds going to relief efforts [Toole, 2018]. Hamilton’s success led to more interest in In the Heights, with a film adaptation releasing in 2021. While the film was criticized for white-washing the Washington Heights neighborhood via its cast, it was praised for its bilingual soundtrack.

Voting in Spanish

Puerto Ricans living on the island cannot vote in US presidential elections, due to the island’s status as a territory. However, those who move to the mainland and establish residency can vote. Voter registration among this group of transplants is, however, rather low among those who are not fluent in English. Despite mandates set out in the Voting Rights Act that require language services to be provided by local election commissions in counties with high populations in need of them, counties with smaller Spanish-speaking populations very often fail to make election materials available in Spanish. As a result of this, in August of 2018, several nonpartisan groups sued the state of Florida, demanding that Spanish-language election materials be provided in all counties, no matter the population size [Hernandez, 2018; Stempel, 2018]. In September of that year, US District Chief Judge Mark Walker of the federal court in Tallahassee ordered 32 counties to provide sample ballots in Spanish [Stempel, 2018]. As evidence that the availability of ballots and election information in Spanish can positively impact the voting turnout among Hispanic populations, it is noteworthy that the 2018 election was affected by this rulting, with “dónde votar” (or “where to vote”) becoming one of Google’s top searches on Election Day [Stewart, 2018].

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

- Genealogy/Relatedness

Puerto Rican Spanish (español puertorriqueño) is the Spanish language spoken in Puerto Rico. It belongs to the group of Caribbean Spanish variants.

Andalusian Spanish (the varieties of Spanish characteristic of the southern Iberian Peninsular region surrounding Seville) became the basis for Puerto Rican Spanish since most of the settlers of Puerto Rico (and the rest of the Spanish Caribbean) came from Andalusia between the 15th and 18th centuries. The influence of Andalusian Spanish is evident in a number of phonological traits. Among these, the endings -ado, -ido, -edo often drop intervocalic /d/ in both Andalusian and Puerto Rican (i.e. Caribbean) Spanish: hablado > hablao, vendido > vendío, dedo > deo. Another Andalusian trait is the tendency to weaken postvocalic consonants, particularly /-s/: los dos > lo(h) do(h), buscar > buhcá(l).

2. Phonetics/Phonology

There are several noticeable phonological traits that distinguish Puerto Rican (i.e. Caribbean) Spanish from Castilian Spanish. Among them is the pronunciation phenomenon called “seseo.” In standard Castilian Spanish, the “s” sounds are pronounced more like a “th” (/θ/) when followed by an /i/ or an /e/ vowel, and a little bit like an “sh” (/ʃ/) when followed by an /a/, /o/, or /u/ vowel. Thus, in Madrid, speakers pronounce the word ciencia ‘science’ like “thienthia” and the word esos ‘those’ like “eshosh.” Andalusian/Caribbean Spanish would use an /s/ in all cases pronouncing them like “siensia” and “esos.”

Another common feature is aspiration or elimination of the /s/ in syllable-final position of unaccented syllables. For example, las rosas ‘the roses’ would be pronounced like “la rosa” (with missing /s/ sounds after the /a/ vowels, rather than “las rosas.”

Additionally, there is a deletion of /d/ between vowels. Castilian Spanish already weakens /d/ between vowels to the “th” sound in “then” (/ð/), such that words like lado ‘side’ are pronounced like “latho” (/laðo/). In Andalusian/Caribbean Spanish, this /ð/ sound is dropped and lado is pronounced like “la’o” (/lao/).

Another noticeable feature is the changing of word final /n/ sounds to “ng” /ŋ/. Thus, a word such as consideran ‘they consider’, instead of being pronounced /konsiðeɾan/, is pronounced like “considerang” /konsiðeɾaŋ/.

Finally, the shortening of words is common in Puerto Rican Spanish. For example, the two syllable Spanish words para, madre, and padre (‘for’, ‘mother,’ and ‘father’) may be pronounced by Puerto Rican Spanish speakers as para =/pa/, madre =/mai/, and padre = /pai/ [Luna, 2010].

3. Morphology and Grammar

Like Castilian Spanish, Puerto Rican Spanish has canonical subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, and overall, the morphology and grammar of Puerto Rican Spanish is similar to that of Castilian Spanish. However, there are some differences. For example, Puerto Rican (i.e. Caribbean) Spanish and Standard Iberian Spanish differ in how they form questions. In Iberian Spanish, the question word and the verb come first, and the subject pronoun is sometimes last and sometimes not there. So, “What are you saying?” comes out as ¿Qué dices tu? ‘what say you’ or ¿Qué dices? ‘what say’. In Caribbean Spanish, the pronoun comes between the question word and the verb, and comes out as ¿Qué tú dices? ‘what you say.’ In addition to this difference Puerto Rican Spanish tends to regularize the conjugation of some standard Spanish irregular verbs [Santoro, 2007].

- Lexicon and Vocabulary

Before arrival of Spanish settlers to Puerto Rico, the island was populated by Taíno tribes, who were an Arawak people who migrated into the Caribbean Islands from the area of present-day Venezuela around 400 BCE [Poole, 2011]. The Taíno population rapidly declined after the arrival of the Spanish, as a result of diseases brought from Europe. At the same time, there was sufficient contact between the Taino and the Spanish colonials for the latter to borrow many lexical items from the Taíno language into Puerto Rican Spanish (e.g., hamaca (‘hammock’), hurakán (‘hurricane’), and tabaco (‘tobacco’)).

In the 16th century, the first African slaves were brought to the island. The kiKongo languages of Central Africa are thought to have had the greatest influence on Puerto Rican Spanish, with borrowed words like gandul (‘pigeon pea’), fufú (‘mashed plantains’), and malanga (‘a root vegetable’) [Lipski, 2001].

In 1898, after Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States as part of a peace treaty ending the Spanish-American War. As a US territory, between 1902 and 1948, the main language of instruction in public schools was English, which led to many American English words becoming a part of the Puerto Rican vocabulary [Beardsley, 2004].

- Orthography/Writing System

Puerto Rican Spanish is written using the Spanish alphabet, which is a traditional Latin alphabet with one additional letter: eñe ⟨ñ⟩, for a total of 27 letters. Although the letters ⟨k⟩ and ⟨w⟩ are part of the alphabet, they appear only in loanwords. Puerto Rican Spanish uses acute accent over any vowel ⟨á, é, í, ó, ú⟩ to mark the stress [Butt & Benjamin, 2011].

- Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

Spanish is the first official language of Puerto Rico, while English is the second official language. Both languages are used by the government of Puerto Rico. English is the primary language of less than 10% of the population. Spanish is the dominant language of business, education and daily life on the island, spoken by nearly 95% of the population [Muniz-Arguelles, 1988].

“Spanglish”

Many Puerto Ricans are bilingual to some extent, particularly those who live in the mainland United States. Bilingualism often leads to a practice known as “code-switching” in informal conversation, where an individual will switch between languages for certain words. Code-switching among Spanish speakers in the United States is prevalent enough that it has become known as “Spanglish.” This word, however, contains many common incorrect assumptions, and therefore it has been denounced by many linguists and bilingual speakers. For example, code-switching does not necessarily mean that the individual is not proficient in either language. Rather, code switching in discourse is a choice, made according to the context and depending on the languages used by the conversation participants. Code-switching may additionally be motivated by the fact that bilingual speakers have, in their bilingual lexicon, some words which are not easily translated from one language to the other. For example, the cabro in Spanish means ‘goat’, and a cabron is technically a ‘large goat’. But cabron is vernacular Spanish means something like ‘dumbass’, and when speaking in English, a bilingual Spanish-English speaker might prefer to use the word cabron in an otherwise English sentence, since they do not mean ‘large goat’ and ‘dumbass’ might be a little too offensive. Thus, code switching often provides individuals with ways to better express their intended meanings, than if they had to rely on one language [Dumitrescu, 2012; Heredia & Altarriba, 2001].

“Spanglish” is not a dialect or language of its own. Code-switching does tend to follow some rules. For example, noun-adjective order must follow the rules of the language of the adjective. In English, adjectives typically come before the noun, and in Spanish they come after. Accordingly, we get rich soup in English, but sopa rica in Spanish. In a code switching situation, a “Spanglish” speaker might say rich sopa or soup rica, but neither sopa rich nor rica soup. These rules, while regular and interesting, are not sufficient to have code-switched English-Spanish count as its own dialect or language.

“Spanglish”-type code switching has also been pointed to when Puerto Rican Spanish speakers were arguing for independence, since for many Puerto Ricans the use of “Spanglish” was held up as evidence that English influence was destroying proper Spanish in Puerto Rico. Conversely, some thought that “Spanglish” was a barrier to Puerto Rican assimilation in the United States. Scholars have pointed out, however, that most code-switchers simply use the practice for ease of informal communication and are fluent in one or both languages. Nevertheless, bilingualism is an important part of the identity of many Puerto Ricans living in the mainland United States [Dumitrescu, 2012; Heredia & Altarriba, 2001].

Resources

References

Alvarez-Gonzalez, J. (1999). Law, Language and Statehood: The Role of English in the Great State of Puerto Rico. Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality, 17(2). Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1536&context=lawineq.

Beardsley, T. S. (2004). American English loanwords in Puerto Rican Spanish. Word, 55(1), 1-10.

Berridge, S. (2015, September). Puerto Rico: A Study of Population Loss Amid Economic Decline. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/beyond-bls/pdf/puerto-rico-a-study-of-population-loss-amid-economic-decline.pdf.

Butt, J., & Benjamin, C. (2011). A New Reference Grammar of Modern Spanish (5th ed.). Oxford: Routledge.

CIA. (2021). The World Factbook: Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 6, 2021, from

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/puerto-rico/.

CIA. (2021). The World Factbook: United States. Retrieved July 6, 2021, from

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/united-states/.

Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. (1952). Retrieved from http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/pue126720E.pdf.

Davies, W, and Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge UP.

Dumitrescu, D. (2012). "Hispania" Guest Editorial: "Spanglish": What's in a

Name? Hispania, 95(3). Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23266135.

EFE. (2015, September 4). P. Rico Senate declares Spanish over English as first official language. EFE. Retrieved from https://www.efe.com/efe/english/life/p-rico-senate-declares-spanish-over-english-as-first-official-language/50000263-2704154.

Glass, R. (1991). Governor Makes Spanish Puerto Rico’s Official Tongue. AP. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/dbeaf63011f29962f42df8e6b8886530.

Greenberg, S., & Ekins, G. (2015, June 30). Tax Policy Helped Create Puerto Rico's Fiscal

Crisis. Retrieved from https://taxfoundation.org/tax-policy-helped-create-puerto-rico-s-

fiscal-crisis/.

Heredia, R., & Altarriba, J. (2001). Bilingual Language Mixing: Why Do Bilinguals Code-

Switch? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 164-168. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182730

Hernández, A.R. (2018, August 16). Florida lawsuit seeks Spanish translation of ballots, alleges

voting rights violations affecting Puerto Ricans. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/florida-lawsuit-seeks-spanish-translation-of-ballots-alleges-voting-rights-violations-affecting-puerto-ricans/2018/08/16/59f7776c-a171-11e8-93e3-24d1703d2a7a_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.898f654d01d3.

Kelly, K. (2019, January 11). Isabel González and US Citizenship for Puerto Ricans. America Comes Alive. Retrieved from

https://americacomesalive.com/2017/10/04/isabel-gonzalez-and-u-s-citizenship-for-puerto-ricans/.

Lederberg, A., & Morales, C. (1985). Code switching by bilinguals: Evidence against a third

grammar. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 14, 113-136. Retrieved from

10.1007/BF01067625.

Library of Congress (2011, June 22). Chronology of Puerto Rico in the Spanish-American War. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/chronpr.html.

Library of Congress (2018). Puerto Rican/Cuban Immigration. (2018). Retrieved from

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/puerto-rican-cuban/.

Lipski, J. (2001). From bozal to boricua: Implications of Afro-Puerto Rican Language in Literature. Hispania, 84(4), 850-859.

Luna, K. V. (2010). The Spanish of Ponce, Puerto Rico: A phonetic, phonological, and intonational analysis. University of California, Los Angeles. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Maldonado, Y. M. (2015, June 15). Military occupation and the Foraker Act. Enciclopedia de

Puerto Rico. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20200801020725/https://enciclopediapr.org/encyclopedia/ocupacion-militar-y-la-ley-foraker/ .

Mathews, T., Wagenheim, O., & Wagenheim, K. (2021). Puerto Rico. Encyclopedia Britanica. Retrived from https://www.britannica.com/place/Puerto-Rico.

Muniz-Arguelles, L. (1988). The Status of Languages in Puerto Rico. University of Puerto Rico. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

Newkirk, V. R. (2017, June 13). Puerto Rico’s plebiscite to nowhere. The Atlantic. Retrieved

Poole, R. M. (2011). What Became of the Taíno? Smithsonian Magazine, October. Retrieved 12 July 2021 from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/.

Robles, F. (2017, June 11). 23% of Puerto Ricans vote in referendum, 97% of them for

statehood. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/11/us/puerto-ricans-vote-on-the-question-of-statehood.html.

Santoro, M. (2007). Puerto Rican Spanish: A case of partial restructuring. Hybrido Magazine, 10(9), 47-57.

Soto, Darren. (2021, June 16). H.R.1522 - Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1522/actions.

Stempel, J. (2018, September 7). US Judge orders 32 Florida counties to help Puerto Ricans

vote. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-florida-election/u-s-judge-orders-32-florida-counties-to-help-puerto-ricans-vote-idUSKCN1LN2MM.

Stewart, E. (2018, November 6). The biggest spike in election searches Tuesday was for “dónde votar”. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/11/6/18069720/midterm-election-latino-vote-donde-votar-google.

Toole, Gerry. (2018, December 26). Lin-Manuel Miranda's Passion for Puerto Rico. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/26/theater/hamilton-puerto-rico-lin-manuel-miranda.html.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Puerto Rico Economy at a Glance. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.pr.htm.

United States Census Bureau. (2019). Quick Facts: Puerto Rico. Retrieved from

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/PR/PST045219.

United States Census Bureau. (2019). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B03001%3A%20HISPANIC%20OR%20LATINO%20ORIGIN%20BY%20SPECIFIC%20ORIGIN&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B03001&hidePreview=true.

Wang, Y.. & Rayer, S. (2018, February 9). Growth Of The Puerto Rican Population In Florida And On The U.S. Mainland. Bureau of Economic and Business Research. Retrieved from https://www.bebr.ufl.edu/population/website-article/growth-puerto-rican-population-florida-and-us-mainland.

Image Credits

Broadway promotional poster [Photograph found in Wikipedia]. (2008). Retrieved from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_the_Heights

Marine69-71 (24 March 2010). Isabel Gonzales and with her husband Juan Francisco Torres.

Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Isabel_Gonzalez_2.JPG.

Matthew-Northrup Company (1897). Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Puerto-Rico---1897.jpg.

Eva Rinaldi (30 April 2015). Ricky Martin @ All Phones Arena Sydney Australia. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ricky_Martin_@AllPhones_Arena_Sydney_Australia_(17321559661).jpg.

Ritratto di Woodrow Wilson pubblicato in copertina del periodico spangnolo La Guerra

Ilustrada [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. (c. 1916). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1914-Woodrow-Wilson.jpg

Spanish-American Treaty of Peace, Paris Dec. 10th 1898 [Photograph found in Wikimedia

Commons]. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kurz_and_Allison,_Spanish-American_Treaty_of_Peace,_Paris_1898.jpg

Velez, W.J. (2017, June 8). Statehood likely to win overwhelming majority in Puerto Rico status

vote. Pasquines. Retrieved from https://pasquines.us/2017/06/08/statehood-likely-win-overwhelming-majority-puerto-rico-status-vote/

Vote Here, Vote Aqui [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons]. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vote_here,_vote_aqui_(3004595893).jpg

William Henry Hunt (1857-1949), of Montana [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons].

(1901). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_H._Hunt.jpg

Credits

Uploaded: July 2021

Previous Versions: June 2020

Contributing Analysts: Nancy Jones and Brianna Surratt

Editors: Gareth Rees-White and Elena Galkina