Synopsis

The Roma people have a long history of statelessness that has contributed to their current language conflict situation. Influenced by many different languages, the Romani language is a collection of diverse dialects [Lee, 1998]. The Roma have been heavily discriminated against since their original migration into Europe in the 14th century CE [Kenrick, 2007]. While they and their language are Indo-European, they are racially distinct from other Indo-European and non-Indo-European (e.g., Hungarian, Estonian) peoples who migrated into Europe before them. Without any widely recognized literary, historical, or religious traditions of their own, the Roma have never “belonged” in any country they settled in, nor collectively organized themselves into a coherent “nation”. Today they remain stateless and scattered, making it difficult to provide them with any uniform legal defense or social protections. . Romani is currently listed as “definitely endangered” on the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger [2017], meaning that Romani children are no longer learning the language as their mother tongue in their homes. As a consequence of this, there is an ongoing effort to codify and then propagate a standard dialect of Romani to help revitalize and protect their language.

Historical Background

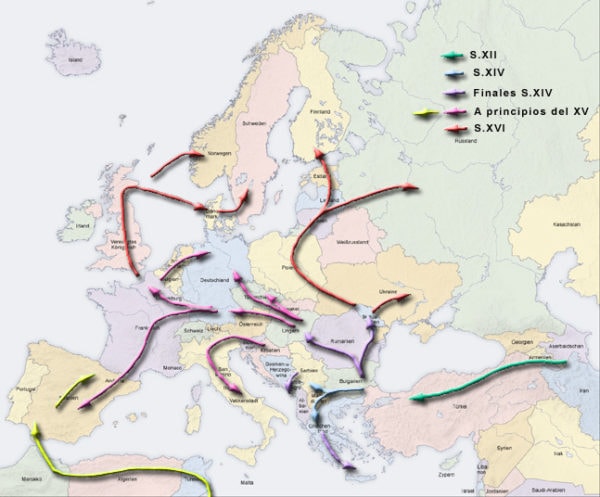

The Roma are a nomadic people who predominately reside in Europe and Turkey. For centuries the prevailing belief was that the Roma originated from Egypt, leading to the slur “gypsy” [Brearley, 1996]. Recent genetic analysis of European Romani populations has revealed that the Roma instead originated from Northwestern India [Mendizabal, I., et al, 2012]. The exodus of the Roma from India is thought to have begun around 500 CE with Roma populations migrating through modern day Turkey and Greece by 1347. The Roma dispersed throughout the whole of Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries, arriving in the British Isles by 1514 [Kenrick, 2007].

The religion, clothing, culture, language, nomadic lifestyle, and skin color of the Roma were markedly different from those of their European contemporaries, resulting in distrust of them and discrimination against them by European governments and peoples. In addition, because the arrival of the Roma into many parts of Northern and Central Europe coincided with the Ottoman Turks’ invasion of the Balkans in the 15th century, Europeans were led to associate the Roma with the Turks, thereby exacerbating their mistreatment as invading outsiders [Silverman, 1995]. Unlike previous groups arriving in Europe, such as the Hungarians and the Turks, “the Roma did not arrive as a conquering people displacing others from their lands. Rather they arrived as migrants and perhaps refugees” [Davies & Dubinsky, 2018]. Despite this, or perhaps because of their perceived helplessness, animosity among Europeans towards the Roma grew. Romani criminal activities in some cities, perhaps provoked by the obstacles they faced in engaging in normal economic activity, led to negative stereotypes of them that exist to this day [Brearley, 1996].

In the mid-to-late 17th century, European governments issued numerous decrees, edicts, and laws, aimed at eliminating Romani populations from within their borders. These called for the forceful deportation of all Roma currently residing in their countries and threatened those who refused to leave with forced deportation, beatings, incarceration and even execution [Brearly, 1996]. By the 18th century, the general failure of these policies resulted in a policy shift towards “the annihilation of Romany identity and language...rather than of the Roma themselves” [Brearley, 1996], and legislation prohibiting Romani language, dress, and their nomadic lifestyle proliferated throughout Europe.

Anti-Romani attitudes in Europe reached a climax during the Holocaust (known in Romani as “Porajmos,” or “the Devouring”) when Nazi Germany and states allied to it carried out the systematic internment and extermination of the European Romani population. During the Holocaust, between 250,000 and 500,000 Roma were killed, equal to over 25% of the Romani population in Europe at the time [United States Holocaust Museum, n.d.]. While the treatment of Roma improved following World War Two, governments in both Eastern Block (i.e., Soviet dominated) and Western (i.e., NATO allied) Europe continued to enact policies aimed at assimilating (and thereby eliminating) the Roma culture and language. Not until the late 1980s did European organizations and individual European governments begin to endorse treaties and other documents that formally recognized the rights, including language rights, of minority populations such as the Roma. Examples of such human rights treaties include the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (1992) and the UN Declaration of the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (1993) [Matras, 2005]. Critics of these treaties argue that most of these documents proved ineffective in protecting the language rights of European Roma, as the policies described in them neither directly addressed the Roma and their circumstances, nor legally bound the countries that signed them to comply with their dictats. Today, European Roma continue to face language discrimination, especially in public education [Safdar A, 2017; New, W., & Kyuchukov, H., 2017].

Roma Educational Policy

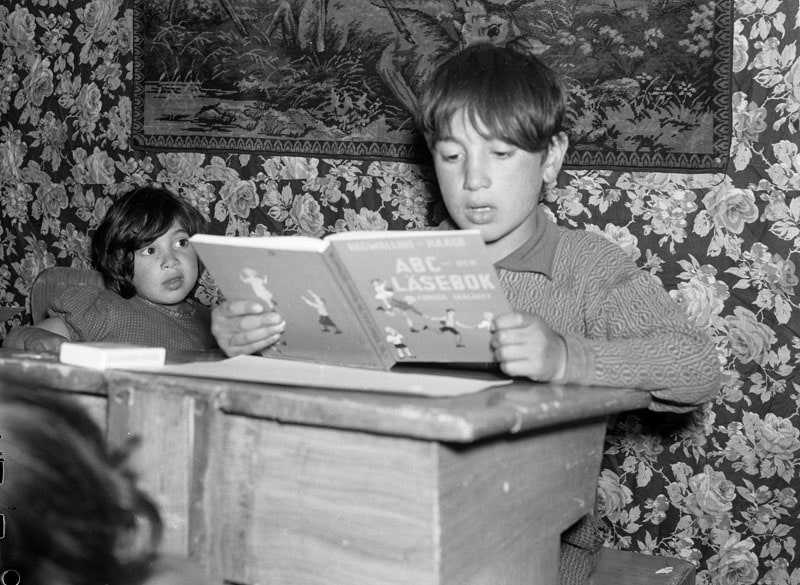

Romani children in Europe continue to face language discrimination in education. Oftentimes, Romani students are separated from their non-Roma peers and placed into different classrooms and schools. Most European governments do not provide Roma children with the opportunity to be taught in their native Romani language. These policies put Roma children at a distinct disadvantage when compared to their non-Roma peers, with only 20% of Roma children completing primary school [UNICEF, 2011].

Language discrimination against the Roma continues in most Europe countries, despite those countries having signed international human rights agreements such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). This convention contains explicit declarations regarding the language rights of minority groups, including the right of children to receive educational instruction in their own native language. It might be pointed out that, in direct contridiction to these treaties, rulings by the European Court of Human Rights – such as in the case of Oršuš and Others V. Croatia (2010) - affirmed that the right to education in a one’s mother tongue is not a human right, and therefore the state is not required to provide for it [New, W. S., Kyuchukov, H., & Villiers, J. D., 2017]. This ruling (and others like it) is based on the contention that if European governments were required to provide education in every native language, their educational systems would be overwhelmed by the linguistic diversity of their citizens and residents. Others, however, have argued that the failure of European institutions to protect Romani language rights demonstrates the inadequacies of the human rights-based approach to combating discrimination against the Roma [New, W., & Kyuchukov, H, 2017].

Discriminatory educational policies continue to fail Roma children by providing them with an inadequate education when compared to their non-Roma peers. These policies have a direct negative impact on the job opportunities available to the Roma, deepening the social and economic divisions between Roma and the non-Roma populations of the countries in which they reside [New, W. S., Kyuchukov, H., & Villiers, J. D., 2017].

Codifying Romani

Beginning in the early 1990s, a loosely interwoven network of activists has raised awareness of Roma rights on the international scale, seeking to allow the Roma equal power over their own culture and language. There are now several European countries, such as Macedonia, Sweden, Finland, and Austria, whose laws or constitutions contain some recognition of the Romani language and rights to use it [Matras, 2018]. In general, there is a push to protect Roma culture and Romani by way of language planning - encouraging teaching, learning, study of and respect for Romani - as well as wider translation and usage of Romani in the media. However, given the lack of an established standard written version of the language, and the great variation between the spoken dialects of Romani, the question of how the language should be codified (i.e., standardized) is difficult.

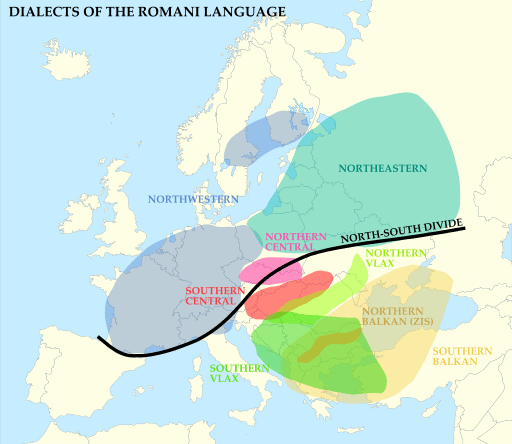

Another obstacle standing in the way of standardization is that no individual agency or oganizations exists that could take on the responsibility of coordinating Roma language standards internationally. Instead, the governments of individual countries have each attempted to perform this task for their own Roma populations. These efforts have resulted in “a dynamic, organic movement...that has yielded results in the form of regional networks of media, publications, and teaching resources” [Matras, 2018]. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, for example, materials are written in the East Slovak dialect of Romani while incorporating aspects of the Czech and Slovak languages. Hungary bases its written Romani form on a local Romani dialect particular to Hungary (Lovari), while Romania has established standards for Romani based yet another local dialect (Kelderash), aspirationally using features from other Romani dialects in an effort to create one “common language” [Matras, 2018]. Other countries, such as Finland, Serbia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Russia, each use a local Romani dialect spoken internally as the basis of their regionally standardized written forms.

Thus, efforts to standardize and preserve Romani are largely local, as are the resources that support them (NGO grants, for the most part). This does not mean that the international Romani movement has no influence over these efforts. “Most if not all of the codification models seek a kind of compromise between the writing system of the respective state alphabet and the 'international' transliteration conventions adopted by linguists” [Matras, 2018]. This is especially the case where the state alphabet deviates greatly from the international system. While the existence of multiple standards, each with its own orthography and borrowed vocabulary might seem to present a problem to the Romani diaspora, it turns out not to be the case, This is because, as Matras explains, “linguistic uniformity and the symbolism attached to it do not, for most Romani cultural activists, constitute and agenda item of high priority” [Matras, 2018]. It turns out that the basic vocabulary and grammar of the Romani dialects don’t generally hamper their mutual intelligibility, and Roma speakers seem to limit their use of the loan words from their country’s majority language when speaking to other members of the diaspora.

The success of Romani codification and preservation efforts, thus, is not to unite all the dialects into one standard language, but rather to facilitate mutual translation among these newly developed and diverse written standards so that access to Romani resources expands throughout the Romani speaking world.

Compare Language Similarities

Linguistic Background

Linguistic Background

1. Genealogy/Relatedness

Romani (řomani čhib) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Europe. It is the only Indo-Aryan spoken exclusively outside the Indian subcontinent [Schrammel & Halwachs, 2005].

The total population of Romani speakers is estimated at 3.5 million with the largest concentrations in southeastern and central Europe, especially Macedonia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia [Matras, 2006].

The Romani language is a relatively unique linguistic case. Instead of being one single, codified language, the linguistic evolution over time has resulted in an array of dialects so diverse that codifying them underneath one “Romani language” umbrella is difficult. Comparative linguistic studies in the early 1900s, however, have linked Romani dialects most closely to Indo-Aryan; genetic studies have since supported this theory by linking the Roma to Dalits in northwestern India. Large parts of the Romani vocabulary were also borrowed from Greek, as well as some phonetic and syntactic features. These characteristics stem from the time the Roma inhabited areas controlled by the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia during the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. Their history of migration, however, especially the extensive population movements that came as a result of the Black Death in the 1300s and the toppling of the Byzantine empire in the 1500s, resulted in the Roma spreading out more broadly throughout Europe and led to the Romani language borrowing heavily from other languages as well Turkish, Romanian, Hungarian, German, and some Slavonic languages have had the most influence on Romani in these more recent times [Matras, 2006].

2. Phonetics/Phonology

The Romani vowel system generally includes five vowels /a, e, i, o, u/; additionally, in some dialects a central vowels /ə/ or /ɨ/ are present. Western European dialects of Romani tend also to have phonemic vowel length distinctions. Typical Romani includes 25 consonants, and some dialects may include additional consonants (for reasons alluded to below). Romani distinguishes between voiced /b, d, g, tʃ/, unvoiced /p, t, k dʒ/ and aspirated stops and affricates /ph, th, kh, tʃʰ/. Nasals are /m/ and /n/, fricatives are /f, v, x, h, s, z, ʃ/, and in some dialects also /ʒ/, and there is an affricate /ts/. All dialects have /l/ and /r/, and some also retain /ř/, which is realized as either a uvular [ʀ], a long trill [rr], or in some dialects a retroflex [ɽ,ɻ]. Palatalization of consonants, either distinctive or non-distinctive, is common in the Romani dialects of Eastern and Southeastern Europe [Matras, 2006].

Outside of the conventional Romani phonology, the phonemic inventory of individual Romani dialects often includes additional phonemes drawn from the languages with which Romani has had contact with and borrowed words from. [Matras, 2006]

3. Morphology and Grammar

Romani has two grammatical genders (masculine and feminine) and two number distinctions (singular and plural). Nouns are marked for case; which in most dialects is nominative and accusative case. Romani syntax is quite different from most Indo-Aryan languages, and is more similar to the Balkan languages [Matras, 2006]. Linguists argue that in most dialects of Romani SVO order is typical in contrastive sentences and VSO order in thetic sentences [Matras, 2002, 2006].

4. Lexicon and Vocabulary

Romani borrowed lexical items from Iranian languages and Armenian. However, Byzantine Greek had the heaviest impact on the Romani (between the 10th and 13th centuries) and included (in addition to lexical loanwords) phonemes, grammatical vocabulary, and inflectional morphology in nouns and verbs [Matras, 2002, 2006]. Further lexical impacts were had from contact with various neighboring languages in Europe.

5. Orthography/Writing System

For most of its history, the Romani language was an oral language. The first example of written Romani dates to 1542, but the Romani writing did not become fully established until the 20th century when speakers started to implement the orthographic systems of their respective host societies. In the majority of cases, they adopted Latin alphabets (e.g., from Romanian, Czech, Croatian) to write Romani [Matras, 2002].

Today no single standard orthography exists for Romani due to the significant dialectal differences. The majority of academic and non-academic Romani is written using a Latin-based orthography [Matras, 2002]. There are three main writing systems used: the Pan-Vlax system, the International Standard and various Anglicized systems [Hancock, 1995].

Pan-Vlax orthography is based on the Latin script with the addition of several diacritics common to the languages of Eastern Europe, such as the caron ( ˇ ) which is added to letters representing alveolar sounds such as /s/, to represent analogous palatal sounds like “sh” [Hancock, 1995]. Thus, “s” is pronounced like the /s/ in sire and “š” is pronounced like the /ʃ/ in shire. The International Standard orthography uses similar conventions to the Pan-Vlax system with several differences, such as replacing carons with acute accents (i.e., č š ž to ć ś ź). The International Standard orthography also attempts to accommodate dialectal variation, particularly with respect to palatalization of consonants and alternations in the form of case suffixes when they appear in different phonological environments [Matras, 1999]. The third script is the English-based orthography, which is effectively an accommodation of the Pan-Vlax orthography to English-language keyboards, replacing letter with caron diacritics with two letter digraphs (e.g., c, č, š, ž to ts, ch, sh, zh) [Hancock, 1995].

6. Discourse/Sociolinguistic Factors/Influences on Development/History

The Romani language is often referred to as ‘Gypsy.’ It is important to distinguish between Romani, a language spoken by the Řom people, and in-group languages employed in various parts of the world, including in Europe by other populations of so-called service-nomads. There is nevertheless some connection between the two variants: in some regions of Europe (e.g., Britain, the Iberian Peninsula, Scandinavia), Romani speaking communities have lost their language entirely in favor of the dominant language of their adopted country However, even these groups have retained some Romani-derived vocabulary as an in-group code. Such codes, for instance Angloromani (Britain), Caló (Spain), or Rommani (Scandinavia) are usually referred to as Para-Romani varieties [Matras, 2006].

The Romani speakers are non-territorial and have no country or homeland of their own, a fact which has contributed to the absence of a Romani standard language. Another set of factors that have led to Romani having developed so many diverse dialects are “the antisocial pressures from the host societies that continue to divide the Romani-speaking populations” [Davies & Dubinsky, 2018]. Many Roma groups (such as those in western Europe where their numbers are small) have actually given up the Romani language as a result of this discrimination, choosing instead to shift to the language of the surrounding majority population. All that is left of Romani for these groups is a specialized lexicon of about 500 insider Romani words, and these words are only used when speaking among themselves. In Romania, a country with one of the biggest populations of Roma people, only 40% of Roma are native speakers of Romani. As a result, the Roma people are caught between a rock and a hard place, simultaneously perceived both as having no real language of their own and not being proficient enough at the national languages of their residential countries.

Resources

Brearley, M. (1996). The Roma/Gypsies of Europe: A Persecuted People. JPR Policy Paper, 1-

- Retrieved fromhttps://www.bjpa.org/search-results/publication/4653.

Cahn, C. (2001). Smoke and Mirrors: Roma and Minority Policy in Hungary. Retrieved from

http://www.errc.org/roma-rights-journal/smoke-and-mirrors-roma-and-minority-policy-in-hungary.

CIA. (2021). The World Factbook. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/.

Davies, W., & Dubinsky, S. (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights: Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge UP.

Fraser, A. (1995). The Gypsies (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Fragile States Index. (2021). Country Dashboard. Retrieved on 30th June, 2021, from

https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/.

Global Democracy Ranking. (2016). The Democracy Ranking of the Quality of Democracy

- Retrieved on 30thJune,2021, from http://democracyranking.org/wordpress/rank/democracy-ranking-2016/.

Hancock, I. (1995). A Handbook of Vlax Romani. Columbus: Slavica Publishers.

Human Development Reports (2021). Human Development Index (HDI) Ranking. Retrieved on

30th June, 2021, from http://hdr.undp.org/en.

Kenrick, D. (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Retrieved

from http://www.gitanos.org/documentos/1.1-KEN-his_HistoricalDictionaryoftheGypsies.pdf.

Köljing, C., & Hultqvist, S. (2013). Our Romani history. Retrieved from

http://www.varromskahistoria.se/en/.

Lee, R. (1998, October). The Romani Language. Retrieved from

https://kopachi.com/articles/the-romani-language-ronald-lee/.

Matras, Y. (2018). The Future of Romani: Toward a Policy of Linguistic Pluralism. Roma Rights Journal, 1-33. Retrieved on June 30, 2021, from http://www.errc.org/roma-rights- journal/the-future-of-romani-toward-a-policy-of-linguistic-pluralism.

Matras, Y. (1999). Writing Romani: The pragmatics of codification in a stateless language. Applied Linguistics, 20, 481-502.

Matras, Y. (2002). Romani: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matras, Y. (2006). Domari. In Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Languages and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier.

Mendizabal, I., Lao, O., Marigorta, U., Wollstein, A., Gusmão, L., Ferak, V., Kayser, M.

(2012). Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data. Current Biology, 22(24), 2342-2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039.

New, W., & Kyuchukov, H. (2017). Language Education for Romani Children: Human Rights

and Capabilities Approaches. European Education, 50(4), 371-384. doi:10.1080/10564934.2017.1401437.

New, W. S., Kyuchukov, H., & Villiers, J. D. (2017). ‘We don’t talk Gypsy here’: Minority

language policies in Europe. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 5(2), 1-24. doi:10.1515/jolace-2017-0015.

Oprean, O. M. (2011). The Roma of Romania (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). DePaul

University. Retrieved from https://via.library.depaul.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?r eferer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1098&context=etd.

Petrova, D. (2004, May 27). The Roma: Between a Myth and the Future. Retrieved from

http://www.errc.org/cikk.php?cikk=1844.

Reporters Without Borders. (2021). 2021 World Freedom Press Index. Retrieved from

Rosenhaft, E. (2018, September 18). The Genocide of the Roma – and How Commemoration of this 'Forgotten Holocaust' is Shifting. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/the- genocide-of-the-roma-and-how-commemoration-of-this-forgotten-holocaust-is-shifting- 92771.

Safdar, A. (2017, March 01). Government Failing to Educate, Integrate Roma Children.

Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/3/1/government-failing-to-e ducate-integrate-roma-children.

Schrammel, B., & Halwachs, D. W. (2005). Introduction. General and Applied Romani Linguistics. Proceeding from the 6th International Conference on Romani Linguistics. München: LINCOM: p. 1.

Silverman, Carol. (1995, June). Persecution and Politicization: Roma (Gypsies) of Eastern Europe. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/persecution- and-politicization-roma-gypsies-eastern-europe.

UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. (2017). Retrieved June 30, 2021,

from http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php.

UNICEF. (2011). The Right of Roma Children to Education. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/1566/file/Roma%20education%20postition%20paper.pdf.

United Nations. (1989, November 20). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx.

United Nations. (1993, June 25). Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Retrieved June 30, 2021,from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/vienna.aspx.

United States Holocaust Museum. (n.d.). Genocie of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939-1945.

Retrieved from https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/genocide-of-european- roma-gypsies-1939-1945.

Van Husen, W. H., & Sinclair, D. (2014). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History.

World Heritage Encyclopedia. (2017). History of Gypsies. Open Access Publishing. Retrieved from http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/history_of_gypsies#cite_note-kenrick-36.

Image Citations

ArnoldPlaton. (2013). Romani dialects of Europe. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Romany_dialects_Europe.svg

Children stolen by nomads. (1902). Retrieved from https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Enfant_enlevee_par_des_nomades.JPG.

Dbachmann. (2009). Romani population average estimate. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Romani_population_average_estimate.png

Ericsson (1943). Photo of a Romani boy studying in the first school for Romani people in Stockholm. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:L%C3%A4sande_pojke.jpg.

Flag of the Romani people. Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Romani_people.svg

Idrizi. (2010). Roma children studying together with Kosovar children, Primary School Emin Duraku,Gjakove, Kosovo. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roma_children_studying_together_with_Kosovar_children,_Primary_School_Emin_Duraku,_Gjakove,_Kosovo.jpg.

Logo of Decade of Roma Inclusion. Retrieved from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Decade_of_Roma_Inclusion_lo.png

Roma in concentration camp, Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Romani_prisoners_at_Belzec_labor_camp.jpg

The migration of the Romani people through the Middle East and Northern Africa to Europe,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Movimiento_gitano.jpg, public domain

Sémhur. Die Roma in Europa in 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roma_in_Europe_2007_map-de.svg.

Credits

Posted: 12 July 2021

Previous versions: May 2020

Contributing Analysts: Tyler Jackson and Stella Masucci

Editors: Gareth Rees-White, Elena Galkina